4302

Evaluating the myocardial fibre pattern in the equine heart using DTI: Protocol development for very a large ex-vivo sample1Edinburgh Imaging, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 2The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies and The Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Myocardium, Ex-Vivo Applications

We aim to develop a protocol suitable for ex-vivo DTI of the equine heart. DTI on a large sample is challenging because this is already a low SNR technique. The main requirement for good-quality data in a formalin-fixed heart is to reduce TE as much as possible. The protocol recommendations presented here are largely common sense, but the long acquisitions required make troubleshooting extremely time consuming. We thought it important to share these findings for the benefit of other investigatorsINTRODUCTION

In humans and rodents, the left ventricle (LV) contracts during systole by an initial anticlockwise rotation of the entire ventricle, followed by a clockwise rotation at the base and simultaneous anticlockwise rotation at the apex1. In the Thoroughbred racehorse it has been shown that this opposing twist is absent2, with rotation in an anticlockwise direction when viewed from the base. Nevertheless, due to a gradation of rotation from base to apex, there is significant twist generated in the equine left ventricle. The three dimensional arrangement of myocardial fibre organisation is crucial to the electrical and mechanical function of the heart, but there are no studies that have described this microstructure in the equine heart. Cardiac Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) has the potential to evaluate tissue architecture while preserving tissue structure. This technique uses direction dependent diffusion of water along tissues, measured in three dimensions, to determine the alignment of the long axis of myofibers and their helical arrangement in the myocardium. The most commonly-used measure of fibre orientation is the degree of sloping of the myofiber from the chamber-horizontal plane, known as the helix angle3. This technique has been described in humans4 and laboratory species5–7 for example, but not in the equine heart. The aim of this work was to develop a DTI protocol suitable for describing the ventricular myofibre patterns of the equine athletic (Thoroughbred racehorse) heart using DT MRI.METHODS

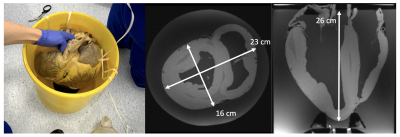

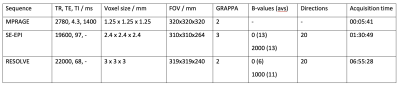

Six hearts were collected post mortem, with owner informed consent, and placed immediately in formalin for fixation. A single heart was used initially to develop an appropriate preparation and scanning protocol. The heart was suspended upright for evaluation in a 15l cylindrical polypropylene tub filled with phosphate-buffered saline. The heart apex was lifted from the pot base using a plastic basketball stand. Solution-soaked sponges were used to stabilise the heart, while minimising contact with the pot sides. Imaging was at 3 T (Siemens MAGNETOM Skyra) using two body array coils over the top of the pot and corresponding spine elements below. Anatomical imaging was with a 3D MPRAGE (sequence parameters in table 1), followed by DTI using a standard SE-EPI sequence (table 1) that had shown good results in a (much smaller) pony heart. The poor results with this sequence led us to use RESOLVE8, which utilises a readout-segmented EPI. This protocol was also used on a second heart, scanned in formalin. Dipy (python 3.7) was used for a simple DTI analysis and visualisation of tracts9.RESULTS

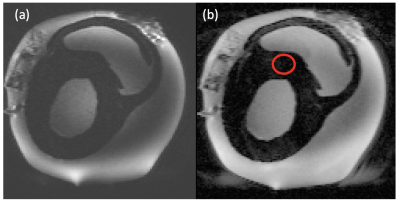

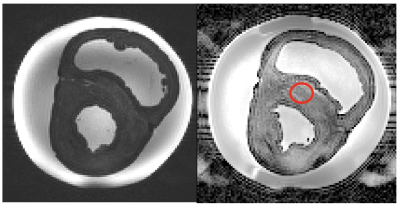

The heart in the tub with MPRAGE examples showing the size of the sample are shown in figure 1. Example SE-EPI images are shown in figure 2. Note the very dark myocardium and distortion. Septal ADC from the marked ROI was only 0.1 ± 0.1 X 10-3 mm2/s with many voxels equal to zero. Example RESOLVE images are shown in figure 3. Septal ADC was 1.8 ± 0.2 X 10-3 mm2/s.DISCUSSION

Formalin fixation has been shown to change MR properties, including T210. This contributed to the very low SNR in the SE-EPI images which had a long TE (97 ms) even with parallel imaging. Switching to the RESOLVE sequence resulted in a shorter TE (68 ms), less distortion and an ADC closer to that reported for the ex-vivo human heart4 but also a longer acquisition. SAR restrictions limited the allowed parameter combinations, particularly when fat saturation was included, but this was important in order to avoid remaining pericardial fat appearing in the myocardial tissue due to fat water shift. The sequence would only run with SPAIR fat saturation if the TR was extended.LV tracts for the two test hearts showed some of the expected appearance. Viewed from the apex upward we see circumferential arrangement of the fibres, with consistent angle over the two hearts scanned. In the formalin heart tracts were less continuous over the RV. Tract directions in the septum were less clearly defined, particularly mid-ventricle. This is probably due to the lower signal from the centre of this large sample. Larger voxels could potentially be tolerated in this structurally well-organised tissue to boost SNR, or potentially additional averages. It seems almost too obvious to state, but alignment of the chambers with the scanner main axes makes interpretation considerably easier, despite the difficulty of rearranging the large heart once already on the scan bed. We had originally intended to scan in fomblin as in previous studies11 but this proved both expensive for the large amount required and difficult to source. In these examples there seems to be little requirement for elimination of air-tissue interface artefacts.This is a first step towards a more comprehensive analysis. Future work will include imaging additional hearts with more detailed tract analysis to allow evaluation of helix angle.

CONCLUSION

DTI on such a large sample is challenging because this is already a low SNR technique. The main requirement for good-quality data in a formalin-fixed heart is to reduce TE as much as possible. The protocol recommendations presented here are largely common sense, but the long acquisitions required make troubleshooting extremely time consuming. We thought it important to share these findings for the benefit of other investigators.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Siemens Collaborative Research Project grant. We thank the LARIF facility for use of their scanner and Radhouene Neji for useful discussions.References

1. Codreanu, I. et al. Longitudinally and circumferentially directed movements of the left ventricle studied by cardiovascular magnetic resonance phase contrast velocity mapping. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 12, 48 (2010).

2. Jago, R. et al. Defining left ventricular twist mechanics in the Thoroughbred racehorse. in Veterinary Cardiology Society Autumn meeting (2020).

3. Nielles-Vallespin, S. et al. Assessment of Myocardial Microstructural Dynamics by In Vivo Diffusion Tensor Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 661–676 (2017).

4. Tous, C., Gentles, T. L., Young, A. A. & Pontré, B. P. Ex vivo cardiovascular magnetic resonance diffusion weighted imaging in congenital heart disease, an insight into the microstructures of tetralogy of Fallot, biventricular and univentricular systemic right ventricle. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 22, 1–12 (2020).

5. Teh, I. et al. Resolving fine cardiac structures in rats with high-resolution diffusion tensor imaging. Sci. Rep. 6, (2016).

6. Teh, I. et al. Validation of diffusion tensor MRI measurements of cardiac microstructure with structure tensor synchrotron radiation imaging. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 19, 1–14 (2017).

7. Holmes, A. A., Scollan, D. F. & Winslow, R. L. Direct histological validation of diffusion tensor MRI in formaldehyde- fixed myocardium. Magn. Reson. Med. 44, 157–161 (2000).

8. Porter, D. A. & Heidemann, R. M. High resolution diffusion-weighted imaging using readout-segmented echo-planar imaging, parallel imaging and a two-dimensional navigator-based reacquisition. Magn. Reson. Med. 62, 468–475 (2009).

9. https://carpentries-incubator.github.io/SDC-BIDS-dMRI/deterministic_tractography/index.html.

10. Lohr, D., Terekhov, M., Veit, F. & Schreiber, L. M. Longitudinal assessment of tissue properties and cardiac diffusion metrics of the ex vivo porcine heart at 7 T: Impact of continuous tissue fixation using formalin. NMR Biomed. 33, 1–14 (2020).

11. Pashakhanloo, F. et al. Submillimeter diffusion tensor imaging and late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance of chronic myocardial infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 19, 1–14 (2017).

Figures