4288

Multi-shell versus single-shell cardiac diffusion imaging1Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 2Medicine (Cardiology), Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains a leading cause of morbidity and death in the Western world. MI causes regional dysfunction, which places remote areas of the heart at a mechanical disadvantage resulting in long-term adverse left ventricular (LV) remodeling and congestive heart failure (CHF). While the cardiac fiber structure has been the topic of study for decades, to this day, it has not been fully understood. There is a need for a deeper understanding of the normal and pathological myocardial structure. Standard techniques using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) which typically needs one b-value (single shell) set of data, yield poor quality data, as DTI is incapable of delineating fibers that form torsions and complex interdigitation. However, multi-shell diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) can delineate these complex fibers. This research investigates the difference between multi-shell versus single shell on the quality of the resulting cardiac tractography applied to an ex vivo normal porcine heart.Introduction

Heart failure is a leading cause of death and the main cause of morbidity in the United States; in 2020, 6.2 million adults had heart failure.1 One major cause of heart failure is myocardial infarction (MI). According to the guidelines regarding myocardial infarction2, cardiovascular imaging3,4 is used to diagnose the loss of viable myocardium. Cardiac MRI includes many techniques for evaluating the heart, its size, function, and the presence of edema and fibrosis. Recently, there have been efforts to perform diffusion in the heart, both in vivo and in vitro, to learn more about the myocardial structural changes following MI. Accordingly, cardiac diffusion tensor imaging (cDTI), based on the tensor model, has been increasingly used to study the tractography of the heart.5-9 However, in voxels with fiber crossings7 or extreme bending, the tensor model is unsuccessful.10-12 The complex architecture of the cardiac muscle fibers13 as well as the heart composition of different cardiac cell types14 (i.e., 11 types), makes the simple tensor model inadequate to depict its fiber architecture. In contrast, Diffusion Spectrum Imaging (DSI) can accurately depict the angular relationships between crossing fibers. 15,16 As it uses the concept of “q-space,” which is analogous to the k-space but with the information of the diffusion encoding gradient vectors of the diffused spins. However, DSI requires prolonged acquisition times, limiting its applicability to clinical settings, even in the brain. On the other hand, multi-shell multi-directional DWI acquisition schemes such as HYbrid Diffusion Imaging (HYDI)17 can resolve intravoxel fiber crossings and target multiple cell populations with different diffusivities.Methods

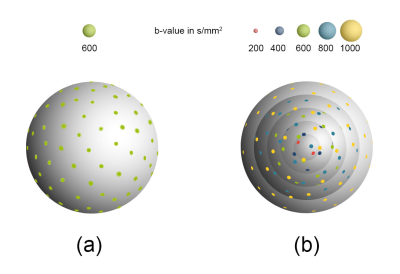

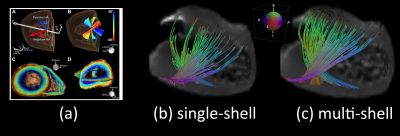

We designed the single-shell and multi-shell diffusion directions using the uniform angular coverage method (See Figure 1). 18 Using these diffusion schemes, we scanned an ex-vivo porcine heart (less than 6 hours after death) to examine the difference between the single-shell diffusion cardiac tractography versus the multi-shell counterpart. The single-shell and the multi-shell diffusion images were acquired on a 3T MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Prismafit; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). The single-shell data was acquired using a RESOLVE diffusion sequence with TR=7720 ms, TE=58 ms, isotropic resolution of 1.4 mm, b-value of 600 s/mm2, TA= 48 mins, a total of 59 diffusion directions, and one non-diffusion weighted volume. For streamlines reconstructions, the DTI diffusion scheme was used, and the restricted diffusion was quantified using restricted diffusion imaging.19 A deterministic fiber tracking algorithm20 was used. The angular threshold was 60 degrees. The step size was randomly selected from 0.5 voxels to 1.5 voxels. The fiber trajectories were smoothed by averaging the propagation direction with 10% of the previous direction. Tracks with a length shorter than 20 or longer than 200 mm were discarded. A total of 1000 tracts were calculated.The multi-shell data was acquired using a RESOLVE diffusion sequence with TR=7720 ms, TE=58 ms, isotropic resolution of 1.4 mm, and the b-values were 200,400,600,800 and 1000 s/mm². The numbers of diffusion sampling directions were 30, 30, 30, 29, and 28, respectively. One additional non-diffusion weighted volume was also acquired. TA=1hr 57 mins. For streamlines reconstructions, generalized q-sampling imaging was used21, and the restricted diffusion was quantified using restricted diffusion imaging.19 A deterministic fiber tracking algorithm20 was used using the same parameters that was used with the single-shell data.

Results

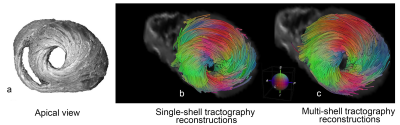

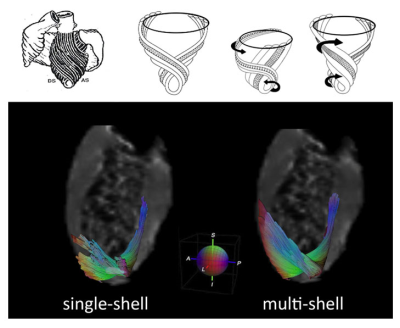

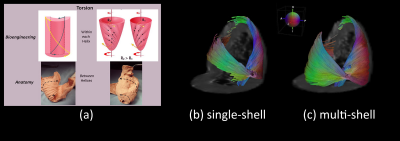

Figure 2.a illustrates the apical view of gross pathology as adapted from 22 of the human heart versus the reconstructed fiber tractography using the single-shell data (b) versus the multi-shell data (c). The upper panel of Figure 3 shows the helical structure as explained in 23, and the same Figure illustrates the helical structure fiber tractography as reconstructed by single-shell data versus multi-shell, using our data and computation. Figures 2-3 show that the tractography of the multi-shell data can delineate the detailed fiber structure more accurately than that of the single-shell data. Figure 4 illustrates the torsion structure of the myocardium: torsion in which the outer muscle (epicardium) has a counterclockwise apex and clockwise base rotation. In contrast, the inner muscle (endocardium) has a clockwise apex and counterclockwise base rotation. Finally, Figure 5 shows that the sheet-like structure is more emphasized in the multi-shell than the single-shell tractography.Discussion and Conclusion

The tractography of the multi-shell data appears to qualitatively define fiber structure more correctly than that of the single-shell data. This is especially true in the areas of twisted architecture or extreme bending. Accordingly, cardiac multi-shell acquisitions and analyses warrant further investigation and validation.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the staff in the Yale Translational Imaging Center for providing the porcine hearts for imaging.References

1. Virani, S. S. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 141, e139-e596, doi:doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 (2020).

2. Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation 138, e618-e651, doi:doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617 (2018).

3. Kim, R. J. et al. The Use of Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Identify Reversible Myocardial Dysfunction. New England Journal of Medicine 343, 1445-1453, doi:10.1056/nejm200011163432003 (2000).

4. Watanabe, E. et al. Infarct Tissue Heterogeneity by Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging Is a Novel Predictor of Mortality in Patients With Chronic Coronary Artery Disease and Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 7, 887-894, doi:doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.001293 (2014).

5. Nielles-Vallespin, S. et al. In vivo diffusion tensor MRI of the human heart: Reproducibility of breath-hold and navigator-based approaches. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 70, 454-465, doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.24488 (2013).

6. Ferreira, P. F. et al. In vivo cardiovascular magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging shows evidence of abnormal myocardial laminar orientations and mobility in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 16, 87, doi:10.1186/s12968-014-0087-8 (2014).

7. Mazzoli, V., Froeling, M., Nederveen, A. J., Nicolay, K. & Strijkers, G. J. in ISMRM, 2014 (Milan, Italy, 2014).

8. Mekkaoui, C. et al. Fiber architecture in remodeled myocardium revealed with a quantitative diffusion CMR tractography framework and histological validation. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 14, 70, doi:10.1186/1532-429X-14-70 (2012).

9. Moulin, K., Verzhbinsky, I. A., Maforo, N. G., Perotti, L. E. & Ennis, D. B. Probing cardiomyocyte mobility with multi-phase cardiac diffusion tensor MRI. PLoS One 15, e0241996, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241996 (2020).

10. Alexander, D. C., Barker, G. J. & Arridge, S. R. Detection and modeling of non-Gaussian apparent diffusion coefficient profiles in human brain data. Magn Reson Med 48, 331-340, doi:10.1002/mrm.10209 (2002).

11. Frank, L. R. Anisotropy in high angular resolution diffusion-weighted MRI. Magn Reson Med 45, 935-939, doi:10.1002/mrm.1125 (2001).

12. Tuch, D. S. et al. High angular resolution diffusion imaging reveals intravoxel white matter fiber heterogeneity. Magn Reson Med 48, 577-582, doi:10.1002/mrm.10268 (2002).

13. Kocica, M. J., Corno, A. F., Lačković, V. & Kanjuh, V. I. The helical ventricular myocardial band of Torrent-Guasp. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. Pediatric cardiac surgery annual, 52-60 (2007).

14. Litviňuková, M. et al. Cells of the adult human heart. Nature 588, 466-472, doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2797-4 (2020).

15. Sosnovik, D. E., Wang, R., Dai, G., Reese, T. G. & Wedeen, V. J. Diffusion MR tractography of the heart. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 11, 47, doi:10.1186/1532-429X-11-47 (2009). 16. Sosnovik, D. E. et al. Diffusion Spectrum MRI Tractography Reveals the Presence of a Complex Network of Residual Myofibers in Infarcted Myocardium. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 2, 206-212, doi:doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.815050 (2009).

17. Alexander, A. L., Wu, Y. C. & Venkat, P. C. Hybrid diffusion imaging (HYDI). Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2006, 2245-2248, doi:10.1109/iembs.2006.259453 (2006).

18. Caruyer, E., Lenglet, C., Sapiro, G. & Deriche, R. Design of multishell sampling schemes with uniform coverage in diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 69, 1534-1540, doi:10.1002/mrm.24736 (2013).

19. Yeh, F. C., Liu, L., Hitchens, T. K. & Wu, Y. L. Mapping immune cell infiltration using restricted diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 77, 603-612, doi:10.1002/mrm.26143 (2017).

20. Yeh, F.-C., Verstynen, T., Wang, Y., Fernández-Miranda, J. & Tseng, W.-Y. I. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PLOS ONE 8, e80713 (2013).

21. Yeh, F., Wedeen, V. & Tseng, W. Generalized q-sampling imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 29, 1626-1635 (2010).

22. Buckberg, G. D. Basic science review: the helix and the heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 124, 863-883, doi:10.1067/mtc.2002.122439 (2002).

23. Buckberg, G. D., Nanda, N. C., Nguyen, C. & Kocica, M. J. What Is the Heart? Anatomy, Function, Pathophysiology, and Misconceptions. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 5, 33 (2018).

Figures