4285

Reproducibility of Cardiac 31P MRS at 7 T – Initial Results of a Multi-Center and Longitudinal Study

Stefan Wampl1, Ladislav Valkovic2, Ferenc Mozes2, Martin Meyerspeer1, and Albrecht Ingo Schmid1

1High Field MR Center, Center for Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2Oxford Centre for Clinical MR Research, RDM Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

1High Field MR Center, Center for Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2Oxford Centre for Clinical MR Research, RDM Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Spectroscopy, 31P MRS

To demonstrate reproducibility of cardiac 31P MR spectroscopy at 7T, three subjects were scanned on two sites in two different countries. The two sites are equipped with similar MR scanners but scanner platform versions, RF coil hardware and operators differed. The 16-channel receive array at site A provided 50% higher SNR than the 14cm single loop coil at site B, while site B achieved better linewidths, resulting in similar quality of spectral fitting. Two scan protocols were compared between the sites, both provided good reproducibility of cardiac PCr/ATP. This demonstrates the feasibility of larger multi-centre trials of cardiac MR spectroscopy.Introduction

Cardiac phosphorus-31 (31P) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) provides markers of myocardial disease [1,2]. The heart’s small size and deep location in the chest incur low SNR. High static magnetic fields like 7 T help remedy this, as does using array coils. It is therefore even more important than usual to test the reproducibility of the method.Methods

The study was conducted in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki in its latest form and with approval of both sites’ Ethics Boards.Part 1: comparison of sites. Three subjects (3m, 33-46 years, BMI 22.4±1.3 kg/m²) were scanned in two different 7 T scanners (Siemens Healthineers, Germany) in two countries within 27 days each. Site A: Scanner platform version Syngo VE12, 14 cm single-loop transmit-receive coil, default cardiac shim; site B: Syngo VB17, single channel transmit, 16 channel receive array coil, tune-up shim. Both coils were manufactured by RAPID Biomedical, Rimpar, Germany. The 31P MRS protocols used were 3D k-space weighted CSI 8x16x8: (I) protocol “short”, untriggered, scan time 6.6 min, as described previously [3], and (II) protocol “long”, triggered, acquisition during end-systole, scan time site A: 18.0±2.3, site B:17.2±0.1 min as in [4]. Acquisitions were performed by three operators with several years experience in cardiac 31P MRS.

Part 2: longitudinal comparison. Four subjects (1f, 26-46 years, BMI 22.1±1.2 kg/m²) were invited twice with more than 260 days between measurements using the protocol "long" at site A.

All spectra were processed and quantified by the same person in MATLAB (Mathworks, USA) using the OXSA toolbox [5]. Voxel-wise flip angle estimations were determined using an external reference, as described previously [6]. The PCr to ATP ratio was quantified for partial T1 saturation and blood contribution based on DPG/ATP [7].

Two voxels in the interventricular septum in two CSI slices were selected and analyzed in each scan. Voxels were selected on datasets from both days with similar locations and compared in a Bland-Altmann plot. Coefficient of variation was calculated. 3-way ANOVA was performed to test for paired differences between sites, protocols and voxel positions.

Results

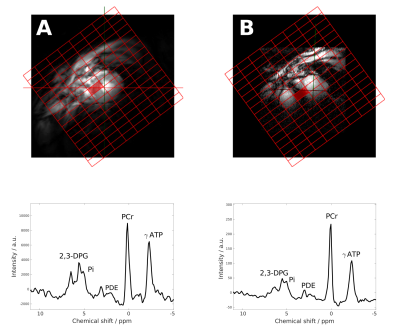

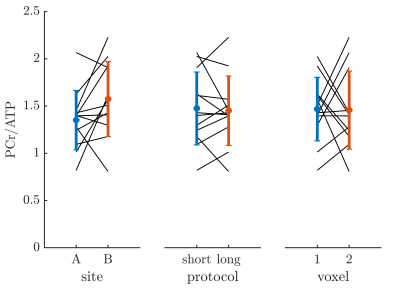

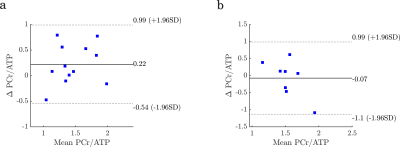

Part 1, site comparison: Data quality was very good on both sites, as can be seen from Figure 1, even inorganic phosphate next to 2,3-DPG can be fitted. One voxel result had to be discarded due to SNR of PCr <10. The data from site B, acquired with the 16-channel array, showed 50 % (p=0.04) higher SNR than site A with the single loop coil. Overall, CRLBs of PCr/ATP were similar with 0.14±0.06 (site A) and 0.12±0.04 (site B), p=0.30, compensated by a better shim at site A. PCr/ATP was reproducible between sites with 1.35±0.31 (site A) and 1.57±0.49 (site B), p=0.16 (see Figure 2), and a coefficient of variation of 26%.No differences in PCr/ATP were found between the two protocols (short: 1.47±0.39, long: 1.45±0.37, p=0.88), however, the long protocol provided significantly better fitting quality (CRLB=0.10±0.03) than the short protocol (CRLB=0.16±0.05, p=0.007). No differences were found for selected voxel position (p=0.94).

Part 2, longitudinal comparison: Good reproducibility was found for repeated measurements after a pause > 260 days between sessions (see Figure 3). No difference in PCr/ATP was found between measurements at different dates (day 1: 1.57±0.45, day 2: 1.50±0.20, p=0.67) or voxels (anterior: 1.67±0.40, posterior: 1.40±0.23, p=0.11). Coefficient of variation between measurement days was 36%.

Discussion & Conclusion

We show that 7 T cardiac 31P MRS is reproducible when using different hardware and scanner platform versions. The triggered, longer protocol has several advantages despite the longer scan time. The SNR is higher even in deeper locations, so more voxels can be analysed, and also Pi is more readily detected [4].This multi-center and multi-operator comparison revealed several of the intricacies related to performing cardiac 31P MRS, while still presenting good reproducibility of PCr/ATP. Particular care was taken to use the same 31P MRS protocols and evaluation methods. However, differences in overall scan execution (e.g. patient setup, coil positioning, CSI grid positioning, shimming procedure) were apparent. Especially the selection of voxels from anatomically similar regions between the sites was challenged by varying quality of cardiac localizers. Also, optimal shimming approaches differed for the two sites (cardiac shim at site A vs. tune-up shim at site B) affecting linewidths and CRLBs.

The experience gained from this small cohort could stimulate further harmonization of cardiac 31P MRS protocols to boost its clinical relevance. More subjects are currently being recruited to confirm these preliminary findings.

To conclude, a larger multi-center trial of cardiac 31P MRS should be performed to underline its clinical feasibility.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project P 28867.References

[1] Bizino MB, et al. Heart 2014;100:881–890. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302546

[2] Neubauer S, et al. NEJM 2007;356(11), 1140–1151. doi:10.1056/NEJMra063052

[3] Ellis J, et al. NMR Biomed 2019;32(6), e4095. doi:10.1002/nbm.4095

[4] Wampl S, et al. Sci Rep 2021;11(1), 9268. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87063-8

[5] Purvis LA et al. PLOS ONE 2017;12(9), e0185356. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185356

[6] Rodgers CT, et al. MRM 2014;72(2), 304–315. doi:10.1002/mrm.24922

[7] Valkovič L, et al. JCMR 2019;21(1), 19. doi:10.1186/s12968-019-0529-4

Figures

Sample

31P MR spectra

from sites A (left) and B (right). Spectra

are acquired using the long

scan protocol with the voxel

selected from similar

locations in the septum as indicated on the short axis localizers.

Comparison

of PCr/ATP between sites, protocols and voxels. Individual

lines show paired measurements from different sites, protocols

or voxels.

Bland-Altmann plots of PCr/ATP for comparison of sites (a) and longitudinal measurements (b).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4285