4210

Diffusion Tensor Imaging in the Lower Leg of a Preclinical Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis1Barrow Neuroimaging Innovation Center, Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, AZ, United States, 2Cancer Systems Imaging, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States, 3University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Diffusion Tensor Imaging

This study examined changes in diffusion tensor parameters during amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progression using a transgenic rodent model. DTI was performed at four timepoints with an even amount of male and female rats to probe sex differences. Leg muscles were excised following scanning for histological analysis. Sex had a statistically significant effect on all parameters. Mean, radial, and axial diffusivity as well as the second eigenvalue were the most sensitive markers of disease progression.

Introduction

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is characterized by loss of spinal and cortical motor neurons, resulting in progressive muscle atrophy and eventually death. While the effects of ALS progression on diffusion MRI (dMRI) metrics in brain and nerves have been investigated,1-4 there has been little research on the same effects in skeletal muscle, particularly in the lower legs. Preclinical models of ALS disease progression provide the most experimentally practical means to characterize and validate the biological underpinnings of dMRI-based parameters since imaging metrics can be directly compared to regional histopathologic features across muscles. In this study, differences in dMRI metrics between an established preclinical ALS model and healthy controls were investigated along with potential sex-differences.Methods

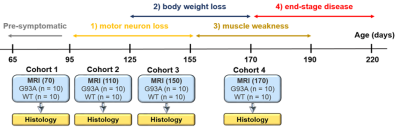

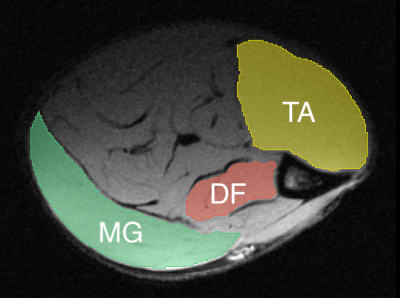

The temporal evolution of muscle degeneration in the SOD1-G93A rat model of ALS has been previously characterized5 and was used to inform imaging timepoints (Figure 1). At each timepoint, 10 control (n=5 female) and 10 SOD1 rats (n=5 female) were imaged using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) before excision of lower leg muscles for histological analysis. Data were gathered at four timepoints: Day 70 (pre-symptomatic), Day 110 (motor neuron loss, but no physical symptoms), Day 150 (weight loss), and Day 170 (muscle weakness). All MR scans were performed on a preclinical Bruker 7T system using a quadrature surface coil. A high-resolution anatomical image was acquired for registration and segmentation purposes. The DTI scan consisted of a 30-direction multi-shot EPI multi-shell acquisition (b = 700, 1400 s/mm2) with TR/TE = 4000/27 ms and 𝛿/Δ = 5/16 ms. An additional field map was acquired for susceptibility correction.Standard DTI preprocessing was done through DIPY6 and Mathematica (Wolfram, Illinois, USA), consisting of denoising, Gibbs ringing correction, EPI distortion correction, and registration. DIPY was also used for fitting of the diffusion tensor and calculation of associated parameters. Segmentations were drawn manually in 3D Slicer7 to delineate the medial gastrocnemius, tibialis anterior, and the deep flexors (Figure 2). Data presented here are from the medial gastrocnemius, with segmentations for the other muscle groups still ongoing. Histology is underway as well to quantify fiber length and fiber Feret diameter for each muscle fiber. A 3-way ANOVA (factors = disease type, sex, timepoint) was conducted in MATLAB (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) with an adjusted p-value of 0.005 used for determining significance.

Results/Discussion

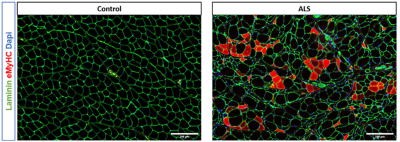

Figure 3 shows the effect of sex and disease state on the diffusion parameters. Sex had a significant effect on all calculated DTI parameters (p<1e-6 for all). Interestingly, time alone had a significant effect on the second eigenvalue (p<0.005). The interaction of disease status and time also had a significant effect for mean, radial, and axial diffusivity and λ2 (p<0.005). No other statistically significant interactions were found for any parameters.The changes in diffusivity were expected and were consistent with previously published results examining histology in ALS8,9 (Figure 4). As ALS progresses, muscle fiber diameter tends to decrease due to structural remodeling; this reduction directly explains the decrease in radial diffusivity (and therefore mean diffusivity) and λ2. It does not, however, explain why time had a significant effect on λ2 regardless of disease status; this is instead indicative of other structural changes occurring naturally during aging. The axial diffusivity decreases are likely caused by the loss of structural integrity of the muscle fibers, leading to increased cellular debris and resulting in more hindered diffusion. The histology results will be used to validate these conclusions.

While the effect of sex in general on diffusion parameters in human skeletal muscle is unclear10,11, these results underline the need to account for sex when designing studies evaluating disease progression and treatment. Sex differences in rate of disease progression have been shown in human and preclinical ALS12, and similar differences were noted in this study.

The disease progression timeline shown in Figure 2 represents the range of time where symptoms may begin to occur; however, at day 170 (the last timepoint) none of the male ALS rats had started experiencing weight loss. This slower progression in males explains why the drastic difference in diffusivity and eigenvalues during the last timepoint is noticed in female ALS rats but not male.

Conclusion

Sex had a significant effect on all parameters, reinforcing the need for inclusion of sex as an independent variable in analysis of disease progression. Mean, radial, and axial diffusivity and λ2 were shown to be sensitive to the combination of disease status and progression, suggesting they might be useful biomarkers for diffusion MRI studies in ALS. Additionally, the histological results will be used to inform dMRI simulations, allowing for further experimentation with different acquisition parameters and techniques.Acknowledgements

NIH/ NINDS R61NS119642-01

NIH/NIAMS 1 R01 AR073831

References

1. Wang S, Poptani H, Bilello M, Wu X, Woo JH, Elman LB, McCluskey LF, Krejza J, Melhem ER. Diffusion tensor imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: volumetric analysis of the corticospinal tract. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Jun-Jul;27(6):1234-8.

2. Baek, SH., Park, J., Kim, Y.H. et al. Usefulness of diffusion tensor imaging findings as biomarkers for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci Rep 10, 5199 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62049-0.

3. Baldaranov D, Khomenko A, Kobor I, Bogdahn U, Gorges M, Kassubek J and Müller H-P (2017) Longitudinal Diffusion Tensor Imaging-Based Assessment of Tract Alterations: An Application to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11:567. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00567.

4. Simon, N.G., Lagopoulos, J., Paling, S. et al. Peripheral nerve diffusion tensor imaging as a measure of disease progression in ALS. J Neurol 264, 882–890 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-017-8443-x.

5. Matsumoto A, Okada Y, Nakamichi M, Nakamura M, Toyama Y, Sobue G, Nagai M, Aoki M, Itoyama Y, Okano H. Disease progression of human SOD1 (G93A) transgenic ALS model rats. J Neurosci Res. 2006 Jan;83(1):119-33. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20708.

6. Garyfallidis E, Brett M, Amirbekian B, Rokem A, van der Walt S, Descoteaux M, Nimmo-Smith I and Dipy Contributors (2014). DIPY, a library for the analysis of diffusion MRI data. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, vol.8, no.8.

7. Kikinis R, Pieper SD, Vosburgh K (2014) 3D Slicer: a platform for subject-specific image analysis, visualization, and clinical support. Intraoperative Imaging Image-Guided Therapy, Ferenc A. Jolesz, Editor 3(19):277-289 ISBN: 978-1-4614-7656-6. www.slicer.org.

8. Bell LC, Fuentes AE, Healey DR, Chao R, Bakkar N, Sirianni RW, Medina DX, Bowser RP, Ladha SS, Semmineh NB, Stokes AM, Quarles CC. Longitudinal evaluation of myofiber microstructural changes in a preclinical ALS model using the transverse relaxivity at tracer equilibrium (TRATE): A preliminary study. Magn Reson Imaging. 2022 Jan;85:217-221. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2021.10.036.

9. Jensen L, Jørgensen LH, Bech RD, Frandsen U, Schrøder HD. Skeletal Muscle Remodelling as a Function of Disease Progression in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:5930621. doi: 10.1155/2016/5930621.

10. Galbán, C.J., Maderwald, S., Uffmann, K. and Ladd, M.E. (2005), A diffusion tensor imaging analysis of gender differences in water diffusivity within human skeletal muscle. NMR Biomed., 18: 489-498.

11. Yanagisawa O, Shimao D, Maruyama K, Nielsen M, Irie T, Niitsu M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2009-01-01, Volume 27, Issue 1, Pages 69-78.

12. Trojsi F, D'Alvano G, Bonavita S, Tedeschi G. Genetics and Sex in the Pathogenesis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Is There a Link? Int J Mol Sci. 2020 May 21;21(10):3647.

Figures

Figure 1: Timeline of disease progression (top) and timepoints of imaging and histology (bottom). Age in days at MRI scans are denoted.

Figure 2: Sample segmentation of muscle taken for histology on representative anatomical image. TA = tibialis anterior, DF = deep flexors, MG = medial gastrocnemius.

Figure 3: Violin plots of fractional anisotropy (left), mean diffusivity (center), and the second eigenvalue (right) by sex and timepoint.

Figure 4: Representative histology from the gastrocnemius of a control (left) and SOD1 (right) rat from our group’s previous work (Bell LC, 2022). Note the increased heterogeneity in cell size and the rounding of the fibers in the ALS model.