4208

Diffusion Tensor Imaging parameters predict quadriceps strength in younger and older healthy adults1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Sarcopenia

The loss of muscle strength was previously thought to be primarily impacted by the loss of muscle volume due to sarcopenia during aging, however, this did not explain why strength declined more rapidly than muscle volume. To better understand this, our study aimed to explore Diffusion Tensor Imaging parameters and their correlations to muscle strength in addition to volume. As expected, volume had a strong positive correlation with all functional strength tests. However, we also observed that radial diffusivity had a significant negative correlation with eccentric functional strength tests, but no correlation was found with the concentric tests.Introduction

Sarcopenia, the natural loss of muscle mass due to aging, is commonly associated with an increased risk of mortality1 and disability in elderly people2. This decline in muscle volume with age has been observed as the primary contributor to loss of muscle strength3. However, strength declines more rapidly than muscle volume, suggesting that not only “muscle quantity” but also “muscle quality” declines with age. Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), an imaging technique that is sensitive to muscle microstructure, has been shown to moderately correlate with muscle power4 and the ratio of muscle extension to flexion strength5. DTI parameters could be sensitive to the microstructural features underlying different strength generation mechanisms, but these have never been investigated. The aim of this study was to explore the association between DTI parameters and concentric, eccentric, and isometric strength in adults over a large age range.We hypothesize that DTI parameters could improve the prediction of muscle strength compared to muscle volume alone.Methods

Eleven healthy adults (5 male, 6 female) between the ages of 30-80 (Avg 54 yrs) with no history of musculoskeletal disease or physical trauma in the past 12 months were enrolled in this study. Both thighs were scanned using a whole-body 3 Tesla MRI scanner (GE Healthcare, Wi, USA), and an 21 channel blanket Air Coil was used for signal reception. The scan protocol consisted of a Dixon scan for anatomical reference (TR=16.4 ms/TE=12 * 1.1 ms, voxel size=1.76x1.76x6, matrix size=256x256x42) and a DTI scan (TR=3500ms, TE=42.6ms, voxel size=3.6x3.6x6mm, matrix size = 126x126x42, SPAIR+SSGR fat suppression, 15 directions at b=400s/mm2 + 3 b0, images, NSA=3). Both scans were performed in 2 different stacks to cover the entire thigh, and then stitched together after postprocessing. The quadriceps femoris (QF) muscles were manually segmented from the out-of-phase images of the Dixon scan, and their volume was calculated (Table 2). The DTI scans were denoised using a Local PCA algorithm, then registered to the anatomical reference, and then used to calculate Radial Diffusivity (RD), Axial Diffusivity (AD), Fractional Anisotropy (FA), and Mean Diffusivity (MD).Every subject completed a series of functional tests using an isokinetic dynamometer (Humac Norm, Computer Sports Medicine, Inc., MA, USA) to measure quadriceps strength. Participants first performed five 5-sec knee extensor isometric (ISOM) contractions of the QF at 60° knee flexion with a rest period of at least 15 seconds between each repetition to reduce muscle fatigue. Next, participants performed five consecutive knee extension and flexion isokinetic exercises at a speed of 90 °/sec for the concentric (CONC90) and 45 °/sec for the eccentric (ECC45). This test was repeated at a speed of 120 °/sec for the concentric (CONC120) and 60 °/sec for the eccentric (ECC60). Participants were instructed to push and resist at their maximal effort for the entire duration of the set (Table 1). The peak torque value was normalized by volume and used for comparison to the DTI parameters.

A multiple regression model was used to investigate the effect of age, sex, volume and DTI parameters on muscle strengths. Variables with p<0.05 values were considered significant and p<0.1 as approaching significance.

Results

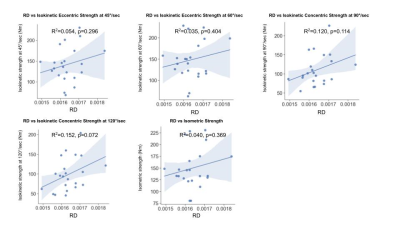

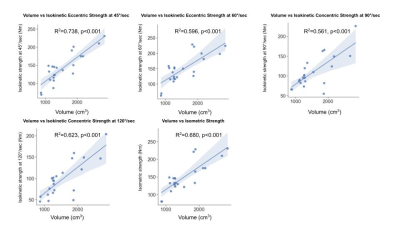

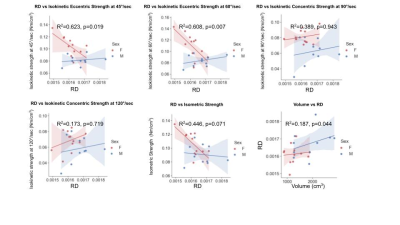

Age had no significant correlation with ECC45, ECC60, and ISOM (p>0.1), however, a strong negative correlation with CONC90 (R2=0.332, p=0.005) and CONC120 (R2=0.519, p<0.001) was observed. Volume was positively correlated with ECC45 (R2=0.738, p=0<001), ECC60 (R2=0.596, p<0.001), ISOM (R2=0.680, p<0.001), CONC90 (R2=0.561, p<0.001), and CONC120 (R2=0.623, p<0.001) (Table 4). FA showed a significant correlation with ECC45 (R2=0.268, p=0.014), while approaching significance with ECC60 (R2=0.155, p=0.069), CONC120 (R2=0.140, p=0.086), and ISOM (R2=0.172, p=0.055) and no correlation with CONC90 (p>0.1). There were no significant correlations between MD and AD and the functional strength tests (p>0.1). Lastly, RD also showed no significant correlation to any of the functional strengths (p>0.1) (Table 3). However, when normalized for volume and accounting for sex differences, RD showed a significant negative correlation with ECC45 (R2=0.623, p=0.019), ECC60 (R2=0.608, p=0.007) while approaching significance with ISOM (R2=0.446, p=0.071), however, no significant correlation was found with CONC90 and CONC120 (p>0.1) (Table 5).Discussion and Conclusion

Our results indicate that volume is the main determinant of muscle strength, as already reported3,6. As expected, we did not find any correlation between AD and strength. The negative correlation between RD and eccentric and isometric strength disagrees with previous literature4,5. However other studies did not normalize for volume and our data shows that volume is significantly positively correlated with RD. RD showed a strong correlation with eccentric strength, when correcting for sex, but not concentric strength. Since eccentric force production is thought to be related to the extracellular matrix, our results could indicate that at relatively short mixing times (about 18ms) we are measuring diffusion contribution from outside the cell. While further research will be needed to identify the exact cause of the dependence of strength on diffusion parameters, our results clearly highlight the connection between measures of muscle water diffusivity and several force generating mechanisms. As muscle loss is associated with increased risk of falling, injuries, and mortality, understanding the factors that contribute to it is and being able to monitor them objectively are critical first steps in creating effective interventions for older adults.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and GE Healthcare.References

1.Anne B. Newman, Varant Kupelian, Marjolein Visser, Eleanor M. Simonsick, Bret H. Goodpaster, Stephen B. Kritchevsky, Frances A. Tylavsky, Susan M. Rubin, Tamara B. Harris, on Behalf of the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study Investigators, Strength, But Not Muscle Mass, Is Associated With Mortality in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study Cohort, The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Volume 61, Issue 1, January 2006, Pages 72–77, https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.1.72

2.Richard N. Baumgartner, Kathleen M. Koehler, Dympna Gallagher, Linda Romero, Steven B. Heymsfield, Robert R. Ross, Philip J. Garry, Robert D. Lindeman, Epidemiology of Sarcopenia among the Elderly in New Mexico, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 147, Issue 8, 15 April 1998, Pages 755–763, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009520

3.Hughes, V. A., Frontera, W. R., Wood, M., Evans, W. J., Dallal, G. E., Roubenoff, R., & Fiatarone Singh, M. A. (2001). Longitudinal muscle strength changes in older adults: Influence of muscle mass, physical activity, and health. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56(5), B209-B217. doi:10.1093/gerona/56.5.B209

4.Klupp, E., Cervantes, B., Schlaeger, S., Inhuber, S., Kreuzpointer, F., Schwirtz, A., Rohrmeier, A., Dieckmeyer, M., Hedderich, D. M., Diefenbach, M. N., Freitag, F., Rummeny, E. J., Zimmer, C., Kirschke, J. S., Karampinos, D. C., & Baum, T. (2019). Paraspinal Muscle DTI Metrics Predict Muscle Strength. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI, 50(3), 816–823. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26679

5.Scheel, M., Prokscha, T., von Roth, P., Winkler, T., Dietrich, R., Bierbaum, S., Arampatzis, A., & Diederichs, G. (2013). Diffusion tensor imaging of skeletal muscle--correlation of fractional anisotropy to muscle power. RoFo : Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Rontgenstrahlen und der Nuklearmedizin, 185(9), 857–861. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1335911

6.Mitchell, W. K., Williams, J., Atherton, P., Larvin, M., Lund, J., & Narici, M. (2012). Sarcopenia, dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength; a quantitative review. Frontiers in physiology, 3, 260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2012.00260

7.Knee Flexion and Extension. (2019). www.crossfit.com. Retrieved November 4, 2022, from https://www.crossfit.com/essentials/movement-about-joints-part-6-knee.

Figures

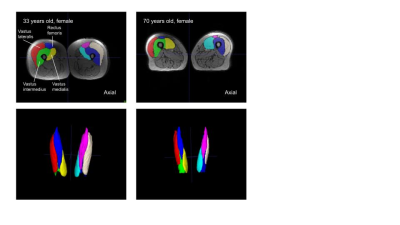

Figure 2. Manual ITK-SNAP segmentations of Quadriceps Femoris

Visual comparison of muscle volume between Subject 1 (33 years old) on the left and Subject 2 (70 years old) on the right. Segmented muscles of the Quadriceps Femoris include vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, rectus femoris, and vastus medialis of both the right and left leg.

Figure 3. Correlation of RD to functional strength tests not normalized for volume

RD showed no significant correlation to all of the functional strength tests including ECC45, ECC60, CONC90, CONC120, and ISOM.

Figure 4. Correlation of volume to functional strength tests

Volume had a significant positive correlation with ECC45, ECC60, ISOM, CONC90, and CONC120.

Figure 5. Correlation of RD to functional strength tests normalized for volume with sex differences

RD had a significant negative correlation with ECC45 and ECC60, and was approaching significance with ISOM. However, RD did not show a significant correlation with CONC90 and CONC120. In addition, RD and a volume had a significant positive correlation.