4178

Exhaustive Comparison of QSM Background Field Removal and Masking using a Realistic Numerical Head Phantom1School of Electrical Engineering, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Valparaiso, Valparaiso, Chile, 2iHEALTH, Millennium Institute for Intelligent Healthcare Engineering, Santiago, Chile, 3University College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Susceptibility, Susceptibility, QSM

Removing background fields is an important preprocessing step in QSM, enabling the reconstruction of fine tissue susceptibility variations in the region of interest (ROI) without being corrupted by susceptibility sources outside of this region. This requires a binary mask of the ROI and most background field removal methods are sensitive to the choice of mask. Here we compared 15 background field removal methods across 4 different masks. We found projection onto dipole fields (PDF) to perform best overall, although it is sensitive to the mask. V-SHARP and RESHARP were more robust to masking and showed good performance.INTRODUCTION

Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) is an ill-posed inverse problem, where tissue susceptibilities are inferred from local magnetic field estimations derived from gradient-echo phase data. The acquired phase is proportional to the macroscopic total field (Btot), which is composed of the local or tissue magnetization fields (Bint) and external or background fields arising from sources outside the region of interest (Bbg) with Btot = Bint + Bbg. Background fields usually are much larger than local fields, but it is possible to disentangle these by exploiting the harmonic property of background fields. Several Background Field Removal (BFR) algorithms have been proposed that utilize different properties of harmonic functions1. These algorithms require the definition of a region of interest (ROI) by means of a binary mask. It has been shown that this ROI definition impacts the quality of the results, but it is unclear how different BFR algorithms are affected by mask selection. Exhaustive comparisons between BFR methods have only been performed using simple simulations (or in vivo data without a ground truth) and a single predefined mask1. Here we present an updated comparison, including new deep learning-based BFR approaches, using a realistic simulated head phantom developed for the 2019 QSM Challenge2 and four different masks.METHODS

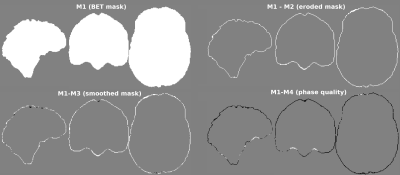

The simulated 1mm isotropic multi-echo gradient-echo complex data from the QSM Challenge Phantom Toolbox2 was used, with and without background fields. Individual echoes were combined using the complex multi-echo nonlinear fitting3 function from the MEDI toolbox, and the result was unwrapped with SEGUE4. The total field map was provided to all BFR algorithms in radians, scaled to deltaTE = 8 ms. Four different ROI masks (see Figure 1) were defined as follows: M1) Brain mask generated by FSL BET5. M2) BET mask eroded using a spherical kernel of one voxel radius. M3) BET mask smoothed using 5-voxel opening and closing morphological operations and then eroded by 1 voxel. M4) BET mask dilated by 1 voxel and then multiplied by a thresholded phase quality map (complex multi-echo fit noise map3 <10-5). A “closing” operation (3-voxel) was used to fill holes inside the mask. The local field ground truth was extracted from the simulated complex data without background fields following the same pipeline.We evaluated the root mean squared error (RMSE) of all local field results within two evaluation masks: E1) The intersection of all BFR masks. E2) The evaluation mask from the 2019 QSM Challenge (2-voxel erosion of M1). E1 is larger than E2. To analyze the mask-related variability of Bint from each BFR method, the normalized standard deviation of Bint across all masks was calculated for each BFR method.

For this comparison we included the following BFR algorithms: 1) Projection onto Dipole Fields, PDF6. 2) Sophisticated Harmonic Artifact Reduction for Phase data, SHARP7. 3) Extended SHARP, ESHARP8. 4) Regularized SHARP, RESHARP9. 5) Variable SHARP, V-SHARP10. 6) Iterative Spherical Mean Value, iSMV11. 7) Spatially Dependant Filtering, SDF12. 8) Multiscale SMV, MSMV13. 9) Multiscale SHARP, MSHARP13. 10) Laplacian Boundary Value, LBV14. 11) LBV adjusted by polynomial fit, pLBV15. 12) HARmonic (background) PhasE RemovaL, HARPERELLA16. We also included deep learning-based algorithms: 13) SHARQnet17. 14) BFRnet18. 15) LapInvNet19. Parameters were optimized to minimize RMSE for each mask, for all BFR methods.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

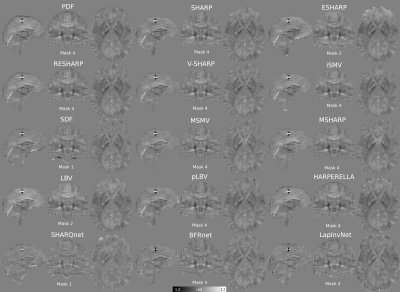

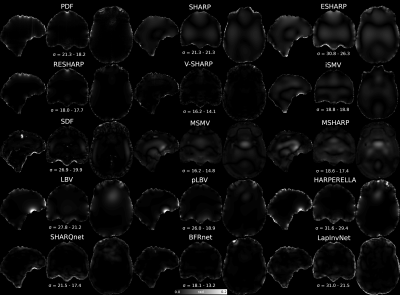

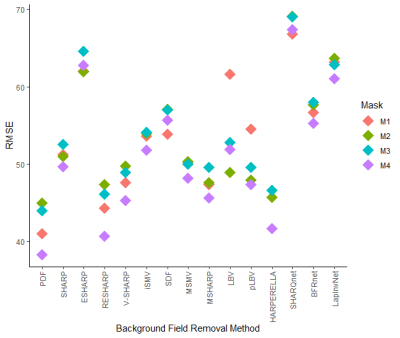

The lowest RMSE Bint for each BFR method is presented in Figure 2, highlighting the best ROI mask. M3 and M2 gave the worst RMSE scores. Error maps from most BFR algorithms do not show anatomical structure inside the brain (Figure 3). However, most SMV based methods (2-9) gave errors near the boundaries (likely due to over-filtering or the reduced output ROI). LBV gave smooth large-scale residuals that were removed by polynomial fitting (pLBV). Deep learning-based solutions gave the largest errors and did not perform well in this dataset.Figure 4 shows the sensitivity of each BFR method to different masks. RESHARP, V-SHARP and BFRnet show low sensitivity inside the brain. MSMV and MSHARP show low sensitivity near the boundaries. LBV is very sensitive in low SNR regions, for example, near the supranasal region. PDF also shows considerable sensitivity near the boundaries, with some sensitivity extending into the brain. This mask-related variability is also shown in Figure 5, where the RMSE scores are compared across all masks.

CONCLUSION

Despite poor overall performance (Figure 3) BFRnet was notably robust against different masks (Figure 4). Current deep learning-based approaches need to improve their generalizability and robustness to be recommended for clinical studies. As suggested before15, this comparison shows that LBV benefits significantly by removing an additional 4th order polynomial as this substantially reduced errors and sensitivity to variable masking.PDF scored best, although it is sensitive to masking. Most algorithms performed best using M4 suggesting the use of a large brain mask with unreliable voxels excluded using a phase quality map. This aligns well with findings in recent literature20.

Given their performance and lower sensitivity to masking, RESHARP and V-SHARP may be good BFR choices for large in-vivo datasets.

Future work will involve evaluation of QSMs estimated from the local fields calculated here to investigate interactions between BFR approaches and dipole inversion algorithms.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cancer Research UK Multidisciplinary Award C53545/A24348 and European Research Council Consolidator Grant DiSCo MRI SFN 770939 for their funding support. Oliver K Kiersnowski’s work was supported by the EPSRC-funded UCL Centre for Doctoral Training in Intelligent, Integrated Imaging in Healthcare (i4health)(EP/S021930/1).References

1. Schweser F, et al. An illustrated comparison of processing methods for phase MRI and QSM: removal of background field contributions from sources outside the region of interest. NMR in Biomedicine 30.4 (2017): e3604.

2. Marques, JP, et al. QSM reconstruction challenge 2.0: A realistic in silico head phantom for MRI data simulation and evaluation of susceptibility mapping procedures. Magnetic resonance in medicine 86.1 (2021): 526-542.

3. Liu T, et al. MRM 2013;69(2):467-76

4. Karsa A, and Shmueli K. SEGUE: a Speedy rEgion-Growing algorithm for Unwrapping Estimated phase. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2018;38.6: 1347-1357.

5. Smith SM, Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human Brain Mapping, 2002, doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062.

6. Liu T, Khalidov I, de Rochefort L, Spincemaille P, Liu J, Tsiouris AJ, Wang Y. A novel background field removal method for MRI using projection onto dipole fields. NMR in Biomedicine. 2011 Nov;24(9):1129-36.

7. Schweser F, Deistung A, Lehr BW, Reichenbach JR. Quantitative imaging of intrinsic magnetic tissue properties using MRI signal phase: an approach to in vivo brain iron metabolism?. Neuroimage. 2011 Feb 14;54(4):2789-807.

8. Topfer R, Schweser F, Deistung A, Reichenbach JR, Wilman AH. SHARP edges: recovering cortical phase contrast through harmonic extension. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015; 73(2): 851–856.

9. Sun H and Wilman AH. Background field removal using spherical mean value filtering and Tikhonov regularization. Magn Reson Med. 2013. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24765

10. Wu B, Li W, Guidon A, Liu C. Whole brain susceptibility mapping using compressed sensing. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2012 Jan;67(1):137-47.

11. Wen Y, Zhou D, Liu T, Spincemaille P, Wang Y. An iterative spherical mean value method for background field removal in MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2014 Oct;72(4):1065-71.

12. Ng A, et al. Spatially dependent filtering for removing phase distortions at the cortical surface, Magn. Reson. Med., 2011;66 (3):784-793

13. Milovic C, et al. Multiscale Spherical Mean Value based background field removal method for Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping. 27th International Conference of the ISMRM, Montreal, Canada, 2019;P4940.

14. Zhou D, Liu T, Spincemaille P, Wang Y. Background field removal by solving the Laplacian boundary value problem. NMR in Biomedicine. 2014 Mar;27(3):312-9.

15. Langkammer C, Schweser F, Shmueli K, Kames C, Li X, Guo L, Milovic C, Kim J, Wei H, Bredies K, Buch S, Guo Y, Liu Z, Meineke J, Rauscher A, Marques JP, Bilgic B; Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping: Report from the 2016 Reconstruction Challenge; Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26830.

16. Li W, Avram AV, Wu B, Xiao X, and Liu C. Integrated Laplacian-based phase unwrapping and background phase removal for quantitative susceptibility mapping. NMR Biomed., 2014;27: 219-227. doi:10.1002/nbm.3056

17. Bollmann S, et al. SHARQnet–Sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction in quantitative susceptibility mapping using a deep convolutional neural network. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Physik 2019;29.2: 139-149.

18. Zhu X, et al. BFRnet: A deep learning-based MR background field removal method for QSM of the brain containing significant pathological susceptibility sources. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.02760 (2022).

19. Gao Y, Xiong Z, et al. Instant tissue field and magnetic susceptibility mapping from MRI raw phase using Laplacian enhanced deep neural networks. NeuroImage. 2022;259:119410

20. Karsa A, Punwani S, and Shmueli K. An optimized and highly repeatable MRI acquisition and processing pipeline for quantitative susceptibility mapping in the head-and-neck region. Magn Reson Med. 2020;84:3206-3222. Doi:10.1002/mrm.28377

Figures