4176

Brain susceptibility and oxygen extraction fraction relate to cognition altered by white matter hyperintensity in cognitively normal elderly1Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States, 4Center for Imaging Science, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Susceptibility, Aging

We investigated associations of brain iron as measured by QSM, global oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) as measured by TRUST and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) as measure by FLAIR, and their possible interactive effects on both global composite and domain-specific cognitive functions in cognitively normal participants. Significant associations were observed between global WMH burden and tissue susceptibility suggesting contributions from small vessel diseases to tissue iron deposition. Negative associations between tissue susceptibility and cognition as well as positive associations between OEF and cognitive performance were observed within participants with low WMH burden, but not as significant in high WMH group.Introduction

Prior evidence suggests that among older cognitively normal participants, higher WMH burden, high β-amyloid levels, and higher cerebral iron levels are negatively associated with cognitive performance.1,2 Furthermore, both iron and oxygen metabolism could be altered in the presence of AD pathology.3 However, the possible combined effects of iron, WMH and oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) on global and domain-specific cognitive functions in cognitively normal adults remain unclear. To address this gap, we investigated the associations of global and domain-specific cognitive functions with brain iron (assessed by QSM), global OEF (derived from T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI), total WMH volume (on FLAIR imaging), and β-amyloid levels (measured by 11C-PiB PET).Methods

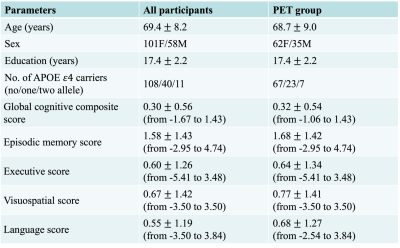

Participants comprised 159 cognitively normal participants (age = 69 ± 8 y/o, 58 males) from the BIOCARD cohort4,5. Among them, 97 participants (PET group) underwent a 11C-PiB PET examination to assess β-amyloid levels (by distribution volume ratio (DVR)) at the same visit as the MRI scan6. Participants completed a comprehensive neuropsychological battery annually, which was used to calculate global4, and domain-specific cognitive composite scores5 (episodic memory, executive functions, language, and visual-spatial processing).The sequence parameters and image processing techniques for QSM2, global OEF7 and total WMH volume8 can be found in previous studies. Twelve regions of interest (ROIs) in superior-and-middle frontal gyrus (SMF), inferior and orbital frontal gyrus (IOF), parietal, temporal, occipital and entorhinal cortex (ENT), cingulate, amygdala, hippocampus, caudate nucleus (CN), putamen (PT) and globus pallidus (GP) were automatically segmented based on human brain atlases (mricloud.org) for quantifying local magnetic susceptibility, DVR and structure volume.

First, multiple regression models were used to assess the relationships between QSM levels (dependent variable) and parameters including age, sex, OEF and WMH. After that, multiple linear regression models, with cognitive scores (global and domain-specific cognition scores) as the outcome, and age, sex, APOE ε4, years of education, WMH, OEF, volume, QSM, and WMH×QSM as well as DVR, OEF×DVR, and WMH×DVR (in the PET group), as predictors were used to test the associations of global OEF, WMH volume (log-transformed to correct for skewness), ROI-based β-amyloid, and tissue susceptibility on cognition. The models were rerun excluding interaction terms with the WMH predictor dichotomized based on tertiles (high = highest tertile and low = lowest 2 tertiles). Benjamini-Hochberg corrections were performed for 12 tests with false discovery rate 0.25.

Results

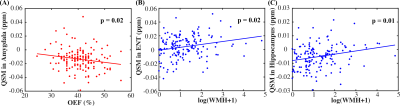

Demographic information for all participants and the PET subgroup is shown in Table 1.Fig. 1(A) shows that OEF was negatively associated with susceptibility values in amygdala (β = -0.17, p = 0.02), while WMH volume was positively associated with susceptibility values in cingulate (β = 0.24, p = 0.01), ENT (β = 0.22, p = 0.02, Fig. 1(B)), amygdala (β = 0.20, p = 0.02) and hippocampus (β = 0.24, p = 0.01, Fig. 1(C)).

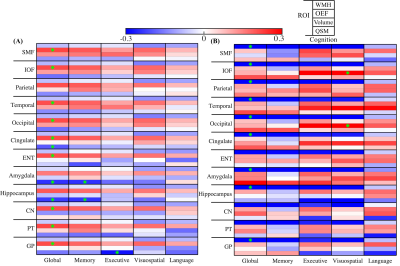

Figure 2 shows negative associations between WMH volume and global cognitive scores in all ROIs, as well as with the domain-specific cognitive scores in most of ROIs. Significantly positive WMH×QSM interactions were found for global cognitive scores in parietal cortex (β = 0.17, p = 0.03), temporal cortex (β = 0.16, p = 0.047), amygdala (β = 0.18, p = 0.02), and for executive scores in parietal cortex (β = 0.17, p = 0.04) and occipital cortex (β = 0.18, p = 0.03).

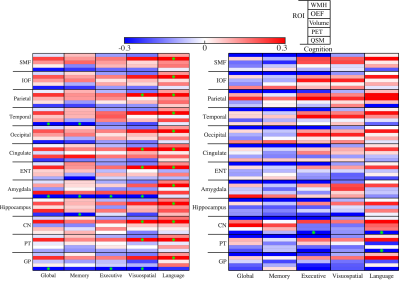

Figure 3 compares the models in low versus high WMH volume group (n = 106 v.s. n = 53). In low WMH group, OEF was positively associated with global cognitive scores in all ROIs except parietal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus (Fig. 3(A)). Susceptibility in amygdala and hippocampus were negatively associated with global cognitive performance (β = -0.24, p = 0.01 in amygdala, β = -0.23, p = 0.02 in hippocampus) and episodic memory (β = -0.24, p = 0.02 in amygdala, β = -0.24, p = 0.02 in hippocampus). Furthermore, negative association was observed in GP (β = -0.28, p = 0.006) between susceptibility and executive function. In high WMH group, there were no associations between susceptibility and cognitive performance; however, significant negative associations were observed between WMH volume and global cognitive scores in all ROIs except ENT, CN and PT. Similar results were obtained in regression without the WMH variable.

In the PET group, significant interaction effects were observed in WMH×PET, WMH×QSM, and OEF×PET. Further group dichotomization with WMH volume confirmed OEF positively associated with cognitive function especially language and more negative associations were found between regional tissue susceptibility and cognition in the low compared to the high WMH group (Fig. 4).

Discussion and conclusion

WMH is a primarily marker of small-vessel cerebrovascular disease.9 In our cognitively normal participants, WMH burden showed associations with regional tissue susceptibility, suggesting potential vascular contributions to increased iron deposition. Second, more negative associations between regional susceptibility and cognitive performance were observed among participants with low compared to high levels of WMH burden, suggesting that the detrimental effects of iron deposition on cognitive performance may be more evident when WMH burden is low. In addition, higher global OEF was associated with higher cognitive performance in the low compared to the high WMH group, suggesting that higher OEF may be related to cognition more strongly when vascular burden is low.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIBIB (P41EB031771) and NIA (R03AG065527, R01AG063842).References

[1] Maillard P, Carmichael O, Fletcher E, et al. Coevolution of white matter hyperintensities and cognition in the elderly. Neurology 2012;79(5):442-448.

[2] Chen L, Soldan A, Oishi K et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping of brain iron and β-amyloid in MRI and PET relating to cognitive performance in cognitively normal older adults. Radiology 2021;298(2):353-362.

[3] Chiang GC, Cho J, Dyke et al. Brain oxygen extraction and neural tissue susceptibility are associated with cognitive impairment in older individuals. J. Neuroimaging 2022;32(4):697-709.

[4] Albert M, Soldan A, Gottesman R, et al. Cognitive changes preceding clinical symptom onset of mild cognitive impairment and relationship to ApoE genotype. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2014;11(8):773-784.

[5] Soldan A, Pettigrew C, Cai Q, et al. Cognitive reserve and long-term change in cognition in aging and preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2017;60:164-172.

[6] Zhou Y, Resnick SM, Ye W, et al. Using a reference tissue model with spatial constraint to quantify [11C]Pittsburgh compound B PET for early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage 2007;36(2):298-312.

[7] Lin Z, Sur S, Soldan A, et al. Brain oxygen extraction by using MRI in older individuals: Relationship to Apolipoprotein E genotype and amyloid burden. Radiology 2019;292(1):140-148.

[8] Soldan A, Pettigrew C, Zhu Y, et al. White matter hyperintensities and CSF Alzheimer disease biomarkers in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2020;94(9):e950-e960.

[9] Attems J, Jellinger KA. The overlap between vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease: lessons from pathology. BMC Med. 2014;12:206.

Figures