4175

Total Field Inversion for Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping Based on Boundary Element Modeling1Shanghai key lab of magnetic resonance, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2Department of Radiology, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Susceptibility, Quantitative Susceptibility mapping, Total Field Inversion

This study proposes a novel total field inversion method in which the background field is modeled by discrete boundary elements. In this method, the boundary value of background field and local tissue susceptibility are simultaneously estimated in one step. We validated our method with orthogonality numerical simulation and in vivo data.Introduction

Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) is a meaningful MRI technique that can map magnetic susceptibility of tissue.1,2 Traditional QSM algorithms execute background field removal and local field inversion sequentially, which causes error propagation across successive operations.2,3 Recently, several single step field-to-susceptibility inversion methods were proposed to calculate tissue susceptibility using total field as input.3,4 Preconditional total field inversion (pTFI) models the background field using the susceptibility distribution outside region of interest (ROI).4 Unfortunately, the local dipoles near boundary of ROI are not orthogonal to the background dipole.5 In this work, we propose a novel TFI method in which the background field is expanded with boundary values based on boundary integral equation.Theory

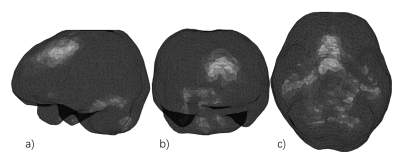

The background field satisfies the Laplace’s equation inside ROI.2,6 This field with smooth surface can be solved using boundary condition in the integral equations as follow7:$$\begin{cases} \frac{1}{2}f_{\varGamma}\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma} \right) =\iint_{\varGamma}{\left( G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma},\boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma}\prime \right) \frac{\partial f_{\varGamma}\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma}\prime \right)}{\partial n}-f_{\varGamma}\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma}\prime \right) \frac{\partial G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma},\boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma}\prime \right)}{\partial n} \right)}dS\prime\\ f\left( \boldsymbol{r} \right) =\iint_{\varGamma}{\left( G\left( \boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}\prime \right) \frac{\partial f_{\varGamma}\left( \mathbf{r}\prime \right)}{\partial n}-f_{\varGamma}\left( \boldsymbol{r}\prime \right) \frac{\partial G\left( \boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}\prime \right)}{\partial n} \right)}dS\prime\\\end{cases},\begin{cases} \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma}\in \varGamma\\ \boldsymbol{r}\in M\\\end{cases}\,\, \left[ 1 \right] $$ Where M is the domain of ROI, Г is the surface of M, f is the background field inside M, r is the location where the field is observed, r′ is the location of the source point and n is the outer normal vector of Г. The function $$$G\left( \boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}\prime \right) =\frac{1}{4\pi \left| \boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{r}\prime \right|}$$$ is the fundamental solution for the Poisson equation.7 In this study, the surface of brain is dispersed by a triangulation mesh. Fig.1 shows the mesh of the surface of brain. Using points located on the barycenter of the triangles on mesh as the discrete boundary elements and assuming that the boundary values within a triangular area are uniform, Eq.1 can be discretized as follow:$$\begin{cases} \frac{1}{2}f_{\varGamma i}\left( \boldsymbol{r} \right) =\sum_{j=1}^{N\,\,}{\left( \iint_{\varGamma j}{G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma i},\boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma j}\prime \right) dS\prime} \right) \frac{\partial f_{\varGamma j}}{\partial n}-\left( \iint_{\varGamma j}{\frac{\partial G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma i},\boldsymbol{r}_{\varGamma j}\prime \right)}{\partial n}dS\prime} \right) f_{\varGamma j}}\\ f\left( \boldsymbol{r} \right) =\sum_{i=1}^{N\,\,}{\left( \iint_{\varGamma i}{G\left( \boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}_i\prime \right) dS\prime} \right) \frac{\partial f_{\varGamma i}}{\partial n}-\left( \iint_{\varGamma i}{\frac{\partial G\left( \boldsymbol{r},\boldsymbol{r}_i\prime \right)}{\partial n}dS\prime} \right) f_{\varGamma i}}\\\end{cases}\,\, \left[ 2 \right] $$ Where the Гi and Гj is the area of the triangular mesh and fГi and fГi is the boundary value of triangle i and j. Eq.2 can be formatted in a matrix form:$$\begin{cases} \boldsymbol{T}\prime\left( \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}_{\varGamma}}{\partial n} \right) =\left( \boldsymbol{Q}\prime+\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol{I} \right) \boldsymbol{f}_{\varGamma}\\ \boldsymbol{f}=\boldsymbol{T}\left( \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}_{\varGamma}}{\partial n} \right) -\boldsymbol{Qf}_{\varGamma}\\\end{cases}\,\, \left[ 3 \right] \\\boldsymbol{T}_{i,j}^{\prime}\,\,=\,\,\iint_{\varGamma j}{G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_i,\boldsymbol{r}_{\mathrm{j}}\prime \right) dS\prime},\,\,\boldsymbol{Q}_{i,j}^{\prime}\,\,=\iint_{\varGamma j}{\frac{\partial G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_i,\boldsymbol{r}_{\mathrm{j}}\prime \right)}{\partial n}dS\prime}\\\boldsymbol{T}_{x,y,z,i}\,\,=\,\,\iint_{\varGamma i}{G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{x,y,z},\boldsymbol{r}_{\mathrm{i}}\prime \right) dS\prime},\,\,\boldsymbol{Q}_{x,y,z,i}\,\,=\iint_{\varGamma i}{\frac{\partial G\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{x,y,z},\boldsymbol{r}_{\mathrm{i}}\prime \right)}{\partial n}dS\prime}\,\,$$ Where I is unit diagonal matrix. Based on Eq.3, a matrix L-1 can be defined as $$$\boldsymbol{L}^{-1}=\boldsymbol{TT}\prime^{-1}\left( \boldsymbol{Q}\prime+\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol{I} \right) -\boldsymbol{Q} $$$. The cost function of our method is formulated as follow:$$\underset{\,\, \left[ \begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol{\chi }\\ \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\varGamma }}\\\end{array} \right]}{\boldsymbol{\chi }=argmin}\,\,\left\| \boldsymbol{m}\cdot e^{i\left( \boldsymbol{D\chi }+\boldsymbol{L}^{-1}\boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\varGamma }}\,\,-\,\,\boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{total}}\,\, \right)} \right\| _{2}^{2}+\lambda \left\| \boldsymbol{M}_G\boldsymbol{\nabla \chi } \right\| _1\,\, \left[ 4 \right] $$Where $$$\boldsymbol{\chi}$$$ is the local tissue susceptibility, m is weighting matrix,8 fГ is the boundary value of background field, ftotal is the total field, MG is the binary edge mask and ▽ denotes the gradient operation.8Methods

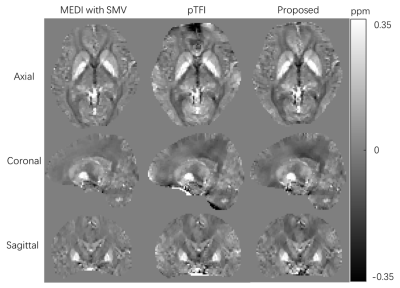

The following experiments were performed to validate the proposed method. We calculated the maximum absolute normalized inner product between the dipole kernel of local susceptibility and components of L-1 for all background field boundary element inside ROI on a typical brain ROI segmented from an actual brain using the following formula:$$c\left( \boldsymbol{r}_{\mathrm{Local}} \right) =\max \left| \left< \boldsymbol{Mask}\cdot \boldsymbol{d}_{local},\left( \boldsymbol{L}^{-1} \right) _{i} \right> /\left( \left\| \boldsymbol{Mask}\cdot \boldsymbol{d}_{local} \right\| _2\cdot \left\| \left( \boldsymbol{L}^{-1} \right) _{i} \right\| _2 \right) \right|$$We compared the susceptibility maps reconstructed by MEDI with SMV kernel,9 pTFI4 and our proposed method on in vivo brain data from a healthy subject. Scan parameters for QSM were as follows: TR/TE1/ΔTE=36/6.2/5.1ms, voxel size=2×2×2 mm3 and bandwidth=240Hz/pixel. The total field map was obtained by nonlinear fitting of the multi-echo GRE data followed by graph cut based phase unwrapping.9,10

Result

Fig.2 shows the good orthogonality between the background model and local dipole field in our method. Fig.3 shows the susceptibility maps reconstructed with three different methods. Our method had a good performance for background field removal. MEDI with SMV kernel suffers from a lack of low-frequency information. For pTFI method, parts of the background field were fitted as local field near the boundary.Discussion

We have implemented the algorithm and obtained preliminary results in a low spatial resolution. The orthogonality between our background field model and local dipole kernel were numerically verified. Good performance of our method was achieved for background field removal on in vivo low-resolution images. Its performance has not been verified on high-resolution images because the L-1 consists of four large scale dense matrixes. And there were still some artifacts in susceptibility map by our method, which may be caused by low precision of surface modeling. Those problems may be solved by using fast multipole method in further study.7Conclusion

This work introduces a novel total field inversion method based on boundary element method. It is shown to have great performance for the separation between background field and local susceptibility.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Rochefort L, Liu T, Kressler B, Liu J, Spincemaille P, Lebon V. Quantitative susceptibility map reconstruction from MR phase data using Bayesian regularization: validation and application to brain imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2010;63(1): 194-206.

2. Wang Y, Liu T. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM): Decoding MRI data for a tissue magnetic biomarker. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2015;73(1):82-101.

3. Chatnuntawech I, McDaniel P, Cauley SF, Gagoski BA, Langkammer C, Martin A, Grantc PE, Wald LL, Setsompop K, Adalsteinsson E. Single-step quantitative susceptibility mapping with variational penalties. NMR in Biomedicine, 2017;30 (4).

4. Liu Z, Kee Y, Zhou D, Wang Y, Spincemaille P. Preconditioned total field inversion (TFI) method for quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2017;78(1):303-315.

5. Liu T, Khalidov I, de Rochefort L, Spincemaille P, Liu J, Tsiouris AJ, Wang Y. A novel background field removal method for MRI using projection onto dipole fields (PDF). NMR in Biomedicine, 2011; 24 (9): 1129-1136.

6. Zhou D, Liu T, Spincemaille P, Wang Y. Background field removal by solving the Laplacian boundary value problem. NMR in Biomedicine. 2014; 27 (3): 312-319.

7. Liu Y. Fast multipole boundary element method: Theory and applications in engineering. Cambridge University Press, 2009: 17-46.

8. Liu J, Liu T, de Rochefort L, Ledoux J, Khalidov I, Chen WW, Tsiouris AJ , Wisnieff C, Spincemaille P, Prince MR. Morphology enabled dipole inversion for quantitative susceptibility mapping using structural consistency between the magnitude image and the susceptibility map. NeuroImage, 2012; 59 (3): 2560-2568.

9. Liu T, Wisnieff C, Lou M, Chen WW, Spincemaille P, Wang Y. Nonlinear formulation of the magnetic field to source relationship for robust quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2013; 69 (2): 467-476.

10. Dong JW, Liu T, Chen F, Zhou D, Dimov A, Raj A, Cheng Q, Spincemaille P, Wang Y. Simultaneous phase unwrapping and removal of chemical shift (SPURS) using graph cuts: Application in quantitative susceptibility mapping. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 2015; 34 (2): 531-540.

Figures