4149

Measuring cellular-interstitial water exchange time in patients with head and neck cancer using time-dependent diffusion experiments

Eddy Solomon1, Gregory Lemberskiy2, Steven Baete2, Kenneth Hu3, Dariya Malyarenko4, Scott Swanson4, Amita Shukla-Dave5, Stephen E Russek6, Elcin Zan2, and Sungheon Gene Kim1

1Radiology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Radiology, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 3Radiation Oncology, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 4Radiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 5Medical Physics and Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, United States, 6National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, CO, United States

1Radiology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Radiology, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 3Radiation Oncology, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 4Radiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 5Medical Physics and Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, United States, 6National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, CO, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Cancer

Cellular-interstitial water exchange time has been suggested to be associated with a number of important cellular properties such as membrane permeability, tumor aggressiveness and treatment response. In this study we investigated the reliability of measuring water exchange times based on diffusivity and diffusional kurtosis at long diffusion times. We used two well-established diffusion phantoms and found that diffusion and kurtosis show stable values over a wide range of diffusion times. In head and neck cancer patients, we found that the Kärger model is a valid model for measuring water exchange time in metastatic lymph node voxels.KEYWORDS

Kärger model; Diffusion Phantom; Kurtosis; STEAM-EPIINTRODUCTION

Diffusion MRI (dMRI) has become the modality of choice to assess the cellular properties of tumors, as the diffusion of water molecules is highly sensitive to tissue microstructure1. However, the diffusivity derived from dMRI acquisition is not a constant for a given biological tissue, but a function of measurement conditions. Specifically, it is important to consider the dependency of dMRI derived parameters on diffusion time2 when a higher-order term of diffusion signal, such as diffusional kurtosis3, is included. Our work investigates how reliably diffusivity and diffusional kurtosis can be measured for long diffusion times (100 - 800 ms). To carry out these experiments, we developed an in-house Stimulated Echo (STEAM-EPI) sequence that can achieve long diffusion time while keeping echo time and b-value constant. Based on well-established diffusion and kurtosis phantoms, we found that time-dependent dMRI measurements can provide stable diffusion and kurtosis values over a wide range of diffusion times. Moreover, estimation of cellular-interstitial water exchange time can be achieved using Kärger model (KM) for the metastatic lymph nodes in head and neck cancer patients.METHODS

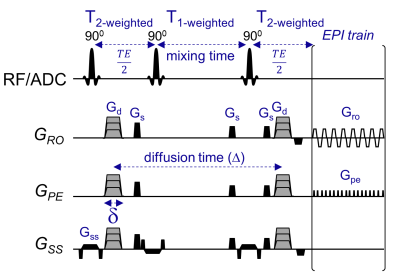

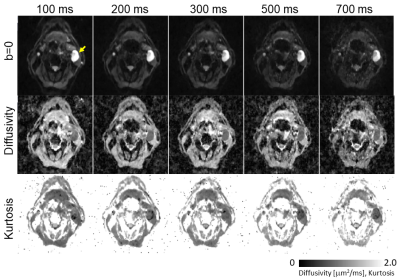

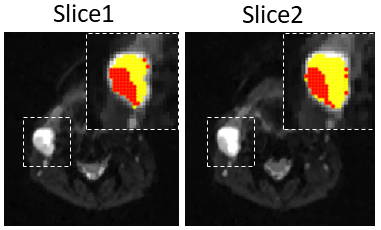

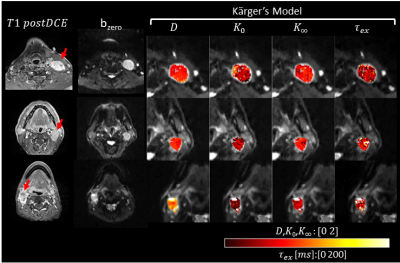

We tested the time-dependent dMRI on two diffusion phantoms. The first phantom is a diffusion phantom provided by National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)4, composed of thirteen 30 ml vials with different polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) concentrations: 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40% and 50%, bathed in ice water. The second phantom is a kurtosis phantom5, composed alcohols and surfactants, creating nanoscopic vesicles, measured at room temperature. Five tonsil biopsy-proven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) patients with metastatic lymph nodes were recruited. All data were acquired with our in-house STEAM-EPI sequence (Fig. 1) on a 3T MAGNETOM Prisma MRI system using a 20-channel head/neck coil array. The STEAM-EPI imaging parameters included: TR/TE=5000/60 ms, resolution=1.5x1.5x4.0 mm3, FOV=190 mm, partial Fourier 6/8, and GRAPPA with R=2. The STEAM-EPI diffusion parameters included $$$\delta$$$ = 15 ms with five diffusion times, [∆ = 100, 200, 300, 500, 700 ms], one b=0 and 4 b-shells [b = 200, 1000, 2000, 3000 s/mm2] with 3 diffusion directions along x, y, and z axes. Each set of images were registered, denoised, de-Gibbsed and corrected for Rician bias. Following post-processing, diffusion and kurtosis maps were generated via a weighted linear least square fit method (Fig. 2). Multi-slice regions of interest (ROI) were drawn for each patient. For each voxel in the ROIs, diffusion and kurtosis were also calculated via a model-based method assuming that for the range of diffusion times $$$D(t)$$$ remains constant (Fig. 3): $$D=(1-v_e ) D_e+v_e D_i=const$$ In this regime, $$$D$$$ is sensitive towards exchanging volume fractions, $$$v_e$$$, whose water exchange time could be determined by modelling $$$K(t)$$$ using the Kärger model (KM)6: $$K(t)=K_∞+K_0\frac{2τ_{ex}}{t} [1-\frac{τ_{ex}}{t} (1-e^{-t⁄τ_{ex}} )]$$ where $$$K_0+K_∞$$$ is the maximum of $$$K$$$ in the case of impermeable barriers and $$$ K_∞$$$ accounts for a partial volume effect. Furthermore, the time dependence of the cumulants $$$D$$$ and $$$K(t)$$$ can be used to estimate diffusion weighted signals: $$S_e (t,b)=S_{e0}(t)exp(-bD+\frac{1}{6}b^2 D^2 K(t))$$ The estimated signal $$$S_e (t,b)$$$ can be linearly scaled by adjusting $$$S_{e0}(t)$$$ to match the measured signal $$$S_m (t,b)$$$ for each diffusion time. Then, estimation of four KM parameters is conducted by minimizing the sum of squared differences between the estimated and measured signals for each voxel: $$\left\{K_0, K_∞, τ_{ex},D\right\}=arg min ∑_{t,b}(S_e (t,b) - S_m (t,b))^2 $$.RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

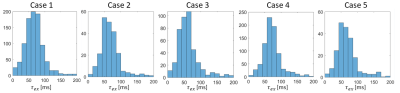

Overall diffusivity variation measured by the NIST phantom, across the diffusion times, was 5.4±3.0%. In the Kurtosis phantom, low concentration samples showed characteristic patterns of low permeability, while high concentration samples showed some permeability characterized by strong diffusivity and kurtosis dependency, over different diffusion time. Figure 2 shows b0 images from a patient with a metastatic cervical node with good SNR and estimated diffusivity and kurtosis maps for each diffusion time. Figure 3 shows a representative case with a lymph node that has a cluster of voxels suitable for KM (red) characterized by constant diffusivity over the diffusion times. For the two slices shown in Figure 3, 47% and 35% of the whole lesion voxels were found suitable for KM analysis, respectively. Figure 4 shows representative parameter maps of three patients using KM analysis. The KM analysis over all five cases, suggested median $$$K_0$$$ between 0.3 and 0.65 and median cellular-interstitial exchange time between 58.5 and 70.6 ms (Figure 5).CONCLUSION

Time-dependent dMRI measurements over a wide range of diffusion times can provide stable diffusion and kurtosis values. Moreover, estimation of cellular-interstitial water exchange time was achieved using Kärger model for the metastatic lymph nodes in patients with head and neck cancer. Future studies will evaluate the prognostic value of these imaging markers.Acknowledgements

NIH grants UH3CA228699, R01CA160620, R01CA219964 and R01EB028774.References

- Moffat BA., et al. Functional diffusion map: a noninvasive MRI biomarker for early stratification of clinical brain tumor response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102(15):5524-5529.

- Novikov DS., et al. Revealing mesoscopic structural universality with diffusion. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111(14):5088-5093.

- Jensen JH., et al. Diffusional kurtosis imaging: the quantification of non-gaussian water diffusion by means of magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 2005;53(6):1432-1440.

- Russek SE. NIST/NIBIB Medical Imaging Phantom Lending Library, National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2021.

- Malyarenko DI., et al. Multicenter Repeatability Study of a Novel Quantitative Diffusion Kurtosis Imaging Phantom. Tomography 2019;5(1):36-43.

- Karger J. Nmr Self-Diffusion Studies in Heterogeneous Systems. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 1985;23(1-4):129-148.

Figures

Figure 1. Time-dependent diffusion and kurtosis experiments using Stimulated-Echo sequence (STEAM). This in-house STEAM sequence allows to use a flexible range of long diffusion times by extending the mixing time. In this study, diffusion times ranging from 100 ms and above were used while keeping TE and b-values constant by adjusting the diffusion weighting gradients (Gd) accordingly.

Figure 2. Representative b=0, diffusivity and kurtosis

images acquired by time-dependent STEAM-EPI diffusion experiments.

Figure 3. Voxels

in the metastatic lymph node which show constant diffusivity (red), along the

different diffusion times, versus non-constant diffusivity (yellow).

Figure 4. Three representative oropharyngeal squamous cell

carcinoma (OPSCC) patients with metastatic lymph nodes, and their parametric

maps as calculated by Kärger model.

Figure 5. Histograms of exchange time values for all five head and neck patient

cases.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4149