4133

Improved 3T Adiabatic T2-Prep for Cardiac T2-Mapping

Ronald J. Beyers1 and Thomas S. Denney1

1MRI Research Center, Auburn University, Auburn University, AL, United States

1MRI Research Center, Auburn University, Auburn University, AL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Myocardium, Cardiomyopathy, T2prep, Mapping, Adiabatic

Cardiac T2-mapping allows quantifying myocardial edema resulting from events, such as, acute myocardial infarction, myocarditis and tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Many T2-mapping sequences exist in literature, however, most have design shortcuts that degrade their consistency, accuracy and prognostic value. We previously reported our sequence that T2-maps at end-systole (ES) for maximum wall thickness, minimized artifacts, and had four-point T2 curve-fits3. Here we present an improved 3T T2prep with four adiabatic pulses to eliminate prep inhomogeneity. This new 3T T2-mapping sequence produces T2maps at ES within 22 seconds breath hold. Pre-testing on phantoms and validation on healthy human volunteers demonstrated superior results.Introduction

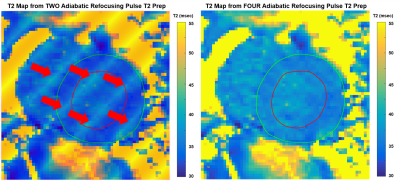

Cardiac MRI (CMR) T2-mapping allows quantified assessment of myocardial edema after such events as acute myocardial infarction, myocarditis and tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy1. CMR sequence must provide maximum diagnostic information with minimum operator effort, time and cost2. Many T2-mapping sequences exist, but most designs have performance-reducing shortcuts including: 1) Imaging during end-diastole (ED) to produce left ventricle (LV) T2maps of the thinnest transmural wall thickness and high wall motion. 2) Acquire only three T2 time-points that give poor three-point curve fits. 3) Includes an ill-defined non-T2prep “time-zero” point that further corrupts the three-point curve-fit. All these features effectively shorten the scan time, but they also degrade the consistency, accuracy and prognostic value of the T2map results.Responding to these shortcomings we previously presented our x4-accelerated, adiabatic T2prep sequence that produces T2 maps at end-systole (ES) for maximum wall thickness, minimum wall motion, and true four-point curve-fits3. However, we found our original 3T T2prep, as well as others in literature4, 5, exhibit prep inhomogeneity when using two adiabatic refocusing pulses under some scan conditions -- corrupting the T2map (see Figure 3, left). Here we present a robust 3T T2prep design that corrects the prep inhomogeneity.

Methods

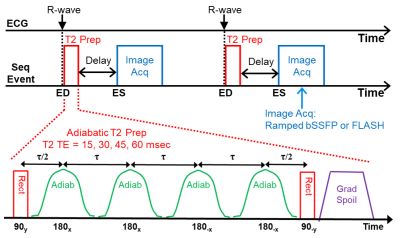

We developed a prospectively ECG R-wave triggered sequence with adiabatic T2prep module, ramped flip angle readout module, and GRAPPA for 3T CMR (see Figure 1). Our original design used hard-rect (flip-down/up) and two adiabatic RF refocusing pulses in the T2prep module that in some conditions exhibited prep inhomogeneity. Our new T2prep module includes four adiabatic pulses run with Malcolm Levitt phase weighting for consistent phase characteristics6. The readout module acquires four successive “mini-cine” images and with selectable balanced steady-state (bSSFP) or fast low-angle shot (FLASH) readout methods. An added adjustable time-delay placed the readout at or just after LV ES. We ran T2 accuracy tests on a myocardium-simulating, CuSO4-doped agar phantom and compared performance to gold-standard T2 spin-echo (SE) results. We ran in vivo scans on four healthy volunteers, 19-26 yo, with informed consent. All scans were run on a 3T Verio clinical scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-chan anterior/posterior RF coil array (Invivo, Gainesville, Florida). All analyses were performed offline with custom Matlab programs (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The T2Prep image at the shortest TE time (TEmin=15ms) had highest blood/tissue contrast and was used to manually segment the LV epi and endocardial boundaries; thereby defining the total LV myocardial ROI for T2map calculation. These ROI were processed by Neider-Mead Simplex Method to per-pixel curve-fit the four T2 time points into T2maps, mean, and standard deviation within the slice and across the four volunteers.Imaging parameters: T2prep TE = 15, 30, 45, 60 ms; T2prep to Readout Delay = 0.33 x ECG RR (typically 280 ms); FOV = 264x246 mm; Pixel size = 2.75x2.75 mm; Matrix = 96x96 (interpolated to 128x128); Slice thickness = 8 mm; GRAPPA accel factor = 4; Flip angle = 35°/10° (bSSPF/FLASH); TE=1.63 ms, TR = ECG RR (typically 850 ms); Bandwidth = 1048 Hz/Pixel; Averages = 1. For human subjects: three mid-LV, short-axis, T2map slices, 8 mm spacing gap, sequentially positioned and scanned. For one subject we repeated the T2prep with two versus four adiabatic pulses to compare performance.

Results

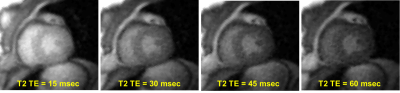

Preliminary T2 quantification on the agar phantom gave T2 = 42.4±3.1 ms and 40.5±1.5 ms (Mean±StdDev) respectively for the T2prep versus T2 SE. Assuming T2 SE as the accurate reference, this made the T2prep result a +4.7% higher (error). All human volunteers completed successful T2prep mapping scans with three slices per subject for a total of nine slices. Each T2map acquisition required a maximum 22 seconds breath hold.Figure 2 presents result T2prep images at the four T2 time-points where successive images show expected magnitude decline as T2prep time increased.

Figure 3 presents a comparison of T2maps using two adiabatic pulses (left) versus four pulses (right). These representative mid-LV T2map images include LV segmentation lines (green and red) transferred after being drawn on the T2Prep TEmin=15 ms image. The left two-pulse T2map shows significant corruption (red arrows) from prep inhomogeneity while the right four-pulse T2map shows good consistency and minimal “bad” mapping pixels.

The three-slice mean T2 results for the three volunteers were 42.5±6.2, 39.6±10.2 and 39.9±8.7 ms and the overall total mean for all nine slices from all three volunteers was 40.7±10.1 ms. The RF specific absorption rate (SAR) with the four-pulse T2prep was high, but still within FDA limits.

Discussion

The change from two to four adiabatic pulses in our T2prep eliminated the prep inhomogeneity with acceptable increase of SAR. The phantom T2prep accuracy as +4.7% higher than SE is acceptably close to validate this adiabatic T2prep method.The in vivo cardiac T2maps with thickened LV walls at ES were easier to segment and process compared to thin-walled ED maps. Interestingly, our T2prep in vivo overall mean myocardial T2 result of 40.7±10.1 ms in young healthy volunteers was lower than the in vivo 50-55 ms range reported by previous literature.

Conclusions

This improved four-pulse adiabatic T2prep CMR T2-mapping sequence creates sufficiently accurate and consistent T2maps at end-systole with a 22 seconds breath hold. This may provide improved prognostic value.Acknowledgements

Special thank you for project support goes to Julie Rodiek, Steven Nichols and Clayton Ridner.References

1. Giri S, et al "T2 quantification for improved detection of myocardial edema", JCMR 2009; 11(56).

2. Edelstein WA, et al “MRI: Time Is Dose—and Money and Versatility”, J Am Coll Radiol 2010;7(8): 650–2.

3. Beyers RJ, Denney TS “Consistent and Accurate 3T Cardiac…” Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 31, 2022

4. Nezafat R, et al “B1-insensitive T2 preparation for improved coronary…”, doi:10.1002/mrm.20835, MRM 55(4) 2006

5. Jenista ER, et al “Motion and flow insensitive adiabatic T2-preparation…”, doi:10.1002/mrm.24564, MRM 2012

6. Beyers RJ, et al "T2-weighted MRI of post-infarct myocardial edema in mice", MRM 2012; 67(1)

Figures

Figure 1: Adiabatic T2Prep T2-mapping Sequence.

ECG-triggered with

a four adiabatic pulse T2prep module, followed by a delay, then a ramped flip

angle readout module (bSSFP or FLASH) acquires four successive images at or

soon after end-systole.

Figure 2: Representative result adiabatic T2prep

image set at the four T2prep times. Note

the image magnitudes show the expected decline as the T2 prep time increases.

Figure 3: T2map comparison of corrupted two-pulse

(left) and nominal four-pulse (right) T2prep. These are mid-LV T2maps with LV

segmentation lines (green and red) transferred after being drawn on a T2Prep TEmin=15

ms image. The four-pulse T2map (right) has

good consistency and minimal “bad” mapping pixels.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4133