4111

Comparing supraclavicular brown adipose tissue fat fraction changes between mild cold and thermoneutrality in healthy adults1Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Endocrine, Fat, Supraclavicular brown adipose tissue

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) is considered a therapeutic target in cardiometabolic health for its capacity to combust triglyceride-derived fatty acids into heat. Previous MRI studies consistently reported reductions in fat fraction (FF) in supraclavicular BAT (scBAT) after cold exposure. However, there is limited research on the validity of this outcome against thermoneutral conditions. We compared scBAT FF dynamics and thermal perception scores between mild-cold and thermoneutrality. Cold exposure decreased scBAT ΔFF (-0.73±0.19%), accompanied with colder thermal perceptions during cooling. At thermoneutrality, two out of three participants also showed a scBAT ΔFF decrease (-0.39±0.06%), yet normal thermal perceptions were reported.Introduction

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) combusts triglyceride-derived fatty acids into heat, and is therefore considered a potential therapeutic target in cardiometabolic health1,2. Cold exposure is a well-established stimulus for BAT activation3, while pharmacological compounds have gained attention as well4. BAT activity is commonly quantified using [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET-CT scans, but the dependence on harmful radiation and its invasive nature hamper its use in clinical stettings5. Alternatively, MRI fat fraction (FF) mapping is a promising, safe and non-invasive method for the assessment of supraclavicular BAT (scBAT) FF6. Previous MRI studies have consistently reported FF reductions in response to cold exposure, but with varying magnitude6,7. However, there is limited research on the validity of this outcome with respect to thermoneutral conditions8. Here, we aimed to compare scBAT FF dynamics and thermal perception scores between 1-hour of mild-cold exposure and thermoneutral control conditions.Methods

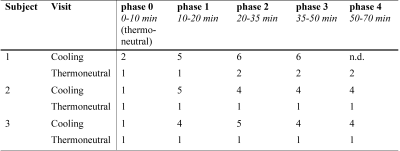

Three healthy volunteers (two females and one male; age: 21.7±1.5 years; BMI: 21.3±1.4 kg/m2) visited the research center twice: participants first underwent a standardized cooling protocol using a water circulating blanket, and 24-48 h later a control measurement was performed at thermoneutrality. During the first visit, the water temperature was initially set to 32°C for 20 min followed by 1-h of mild-cold exposure (18°C). During the second visit, the water temperature was kept constant at 32°C for the entire duration of the experiment. During both visits, thermal perception scores were self-reported every 10-20 minutes throughout the measurement using a numeric rating scale ranging from 1 = “thermoneutral” to 10 = “extreme cold”.Images were acquired during cooling and thermoneutrality at 3T using a 16-channel anterior and 12-channel posterior array and a 16-channel head-and-neck coil. Scans were acquired using a 3D gradient-echo 12-point chemical shift based water-fat separation (Dixon) sequence: TR/TE1/ ΔTE/FA/resolution/FOV/breath-hold duration=12ms/1.12ms/ 0.87ms/3°/2.1 mm isotropic/400x×229×134 mm3/16 s. The acquisition time per scan was 1.03 mins, which yielded 70 dynamics per visit.

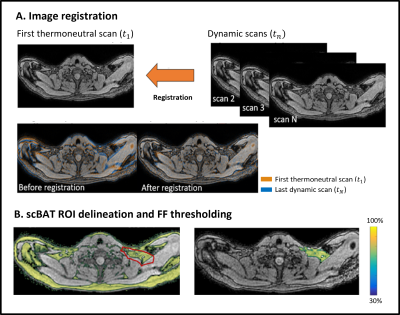

For analysis, the following steps were performed to obtain scBAT FF changes from the cooling visit and thermoneutral measurement separately. First-echo magnitude images of each dynamic were co-registered to the first thermoneutral scan (reference scan) using Elastix12 (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, ROIs were coarsely delineated in the scBAT area on the reference scan. A mutual FF thresholding approach was used to extract scBAT FF, where voxels were included if their FF was above 30% in both the reference scan and in the registered dynamic (Fig. 1B). Voxel-wise FF differences between the reference scan and each dynamic at time point i: ΔFFi (x,y,z) = FFi (x,y,z) - FFTN1 (x,y,z) were calculated and averaged across the ROI. For each participant, a trendline was fitted along the ΔFF scBAT time series for both visits separately. To quantify any decreasing or increasing trends, the vertical distance was determined between the last and first time point along the fitted trendline.

Results

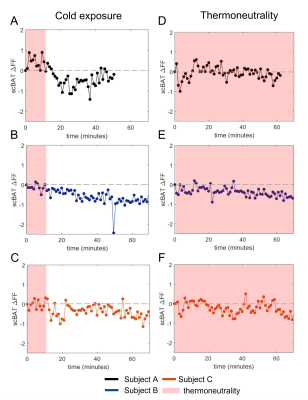

scBAT ΔFF gradually decreased during cooling in participants A and B (-0.92% and -0.76%, respectively; Fig. 2A, B). Participant C also showed a scBAT FF reduction during cooling, yet this response seemed less gradual after the onset of cooling (-0.55%; Fig. 2C). During thermoneutral conditions, scBAT ΔFF decreased in participants B and C (-0.43% and -0.34%, respectively; Fig. 2E, F), whereas no decreasing FF trend was seen for participant A (-0.12% FF; Fig. 2D). Thermal perception scores are provided in Table 1. Participants scored colder perceptions during cooling, whereas normal perceptions were scored during thermoneutral measurements.Discussion

Our data show that scBAT FF decreased during mild-cold exposure, which is most likely attributable to the intracellular combustion of lipids, in agreement with literature6,7. During thermoneutral conditions, two out of three participants also showed a decrease in scBAT FF, albeit in apparently smaller magnitude than during mild-cold exposure. Similarly, a previous report8 showed decreasing scBAT FF trends in 5 out of 11 healthy volunteers during thermoneutral conditions. In their study, cold perception was not determined, and thus no associations between scBAT ΔFF and cold perception could be established. In our study, a normal perception was reported during the entire thermoneutral session. This could be due to BAT activation during the thermoneutral session, but this will need to be confirmed in a larger cohort. Given that active BAT rapidly replenishes intracellular lipid stores by taking up lipids from the circulation, we will compare the scBAT FF changes to plasma lipid measurements at a later stage.Conclusion

Our preliminary results show that scBAT FF decreases in response to mild-cold exposure, but also during thermoneutral conditions in seemingly smaller magnitude. Results of more participants are awaited, and we will focus on exploring the physiological mechanisms that drive the scBAT FF changes during cold exposure and thermoneutrality.Acknowledgements

M.R. Boon is supported by the Dutch Heart Foundation (02-001-2021-B020).References

1. Berbeé JFP, Boon MR, Khedoe PPSJ, et al. Brown fat activation reduces hypercholesterolaemia and protects from atherosclerosis development. Nat Commun. 2015;6. doi:10.1038/ncomms7356

2. Becher T, Palanisamy S, Kramer DJ, et al. Brown adipose tissue is associated with cardiometabolic health. Nat Med. 2021;27(1):58-65. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1126-7

3. Reber J, Willershäuser M, Karlas A, et al. Non-invasive Measurement of Brown Fat Metabolism Based on Optoacoustic Imaging of Hemoglobin Gradients. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):689-701.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.002

4. Cypess AM, Kahn CR. Brown fat as a therapy for obesity and diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17(2):143-149. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e328337a81f

5. Ouellet V, Labbé SM, Blondin DP, et al. Brown adipose tissue oxidative metabolism contributes to energy expenditure during acute cold exposure in humans. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(2):545-552. doi:10.1172/JCI60433

6. Karampinos DC, Weidlich D, Wu M, Hu HH, Franz D. Techniques and Applications of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Studying Brown Adipose Tissue Morphometry and Function. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2019;251:299-324. doi:10.1007/164_2018_158

7. Wu M, Junker D, Branca RT, Karampinos DC. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Techniques for Brown Adipose Tissue Detection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:421. doi:10.3389/FENDO.2020.00421/FULL

8. Gashi G, Madoerin P, Maushart CI, et al. MRI characteristics of supraclavicular brown adipose tissue in relation to cold-induced thermogenesis in healthy human adults. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(4):1160-1168. doi:10.1002/jmri.26733

Figures

FF, fat fraction; scBAT, supraclavicular brown adipose tissue.

Figure 2. Supraclavicular brown adipose tissue (scBAT) fat fraction (FF) changes (A-C) during mild-cold exposure and (D-F) thermoneutral conditions. Red boxes denote thermoneutrality and participants are presented with different colors. For subjects A and B, FF differences of the cooling visit were taken relatively to the second thermoneutral scan, due to an erroneous water-and fat reconstruction and because of an outlier, respectively.