4107

Robust and Automated Processing of Deuterium Metabolic Imaging (DMI) using Spatial Prior Knowledge1Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Deuterium

Deuterium Metabolic Imaging (DMI) is a novel method to generate spatial maps of dynamic metabolism. While DMI acquisition methods are simple and robust, DMI processing still requires expert user interaction, for example in the removal of extracranial natural abundance 2H lipid signals that interfere with metabolism-linked 2H-lactate formation. Here we pursue the use of MRI-based spatial prior knowledge to provide automated and objective lipid removal. Adequate lipid suppression without perturbation of brain voxels is achieved, thereby allowing the generation of distinct and reliable metabolic maps on patients with brain tumors.

Introduction

Deuterium Metabolic Imaging (DMI) is a novel method to map the spatial distribution of 2H-enriched substrates and their metabolic products, whereby DMI has shown promise for unique and clinically relevant metabolic insights in brain tumors (1). DMI sets itself apart from other metabolic imaging modalities through its simple and robust acquisition methods, making it ideally suited for integration in a clinical MR workflow, especially when acquired without prolonging the MR scan protocol through parallel MRI-DMI acquisitions (2). For full integration, the processing of DMI data also needs to become automated and robust. While DMI processing is generally straightforward, some considerations still require expert user intervention. For example, natural abundance 2H lipid signals originating from the skull can interfere with lactate detection, especially in superficial lesions detected with high-sensitivity receive arrays.Here we use the well-defined spatial origin of DMI signals in conjunction with anatomical detail provided by MRI to remove extracranial signals using the SLIM algorithm (3). The processing pipeline, including MRI brain/skull segmentation and SLIM-based regional signal removal, can be fully automated and provides a robust and objective tool to accelerate the inclusion of DMI in a clinical MR workflow.

Methods

DMI was acquired with a pulse-acquire method, extended with 3D phase-encoding according to a spherical k-space sampling pattern. A total of 491 phase encoding steps were acquired to generate a 13 x 9 x 11 DMI dataset in circa 30 min with 8 mL nominal resolution. On human subjects [6,6’-2H2]-glucose dissolved in water was administered orally (0.75 g/kg) after which the metabolic profile was sampled with DMI 90 – 120 min later. Brain and skull ROIs were semi-automatically segmented from 3D gradient-echo MRIs (TR/TE = 25/6 ms). The SLIM algorithm models the DMI data as a linear sum of ROI-specific signals, modulated according to the k-space sampling scheme (3). Signal heterogeneity across ROIs violates the linear model and leads to mixing of ROI-specific signals. To reduce the effects of spatial signal heterogeneity, the skull ROI was divided into 100-150 smaller ROIs. The brain and skull ROIs and the measured DMI data were the primary inputs to the SLIM algorithm, with the ROI-specific 2H MR spectra as the primary output. The ROI-specific 2H MR spectra were used to generate a ‘skull-only’ DMI dataset that was subsequently subtracted from the measured DMI dataset to provide effective lipid signal removal.Results

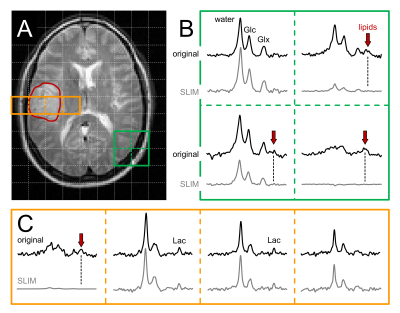

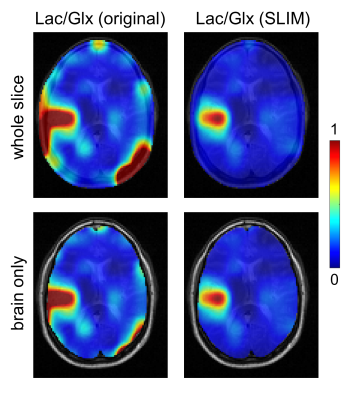

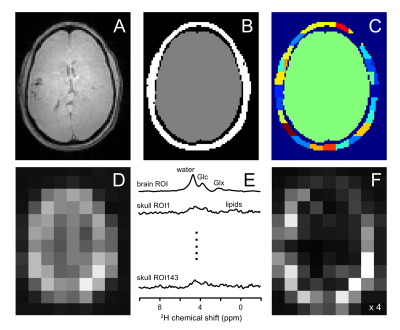

Fig. 1A-C shows MRI segmentation into a single brain ROI and multiple (100-150) skull ROIs. The ROIs in combination with experimental DMI data (Fig. 1D) are the primary inputs to the SLIM algorithm to produce ROI-specific MR spectra (Fig. 1E) that are used to generate skull-only DMI data (Fig. 1F). Subtraction of the skull-only DMI data from the original DMI data removes interfering signals from outside the brain (Figs. 2/3).Figs. 2 and 3 summarize the spectral and spatial performance of the lipid removal algorithm on 3D DMI data from a patient with a glioblastoma brain tumor. Multiple locations show a significant natural abundance lipid signal (red arrows). While the 2H lipid signals are four orders of magnitude lower than the corresponding 1H lipid signals, their amplitude is significant enough to give ambiguity in detecting metabolically produced 2H-lactate. Using prior knowledge on the spatial origins of the signals leads to removal of extracranial signals, while retaining the metabolic profile in brain and tumor tissue. Note that SLIM also removes lipid signals that contaminate brain voxels through PSF-based signal bleeding. However, this effect is generally minor due to the low-intensity of extracranial 2H lipid signals.

Conclusions

The use of spatial prior knowledge in DMI processing allowed the removal of extracranial lipid signals in human subjects to below the spectral noise level. Similar approaches have previously been used for lipid signal removal in 1H MRSI (4,5). However, 1H MRSI requires lipid signal suppression factors well in excess of 100. This puts much higher demands on accurate prior knowledge and signal homogeneity and may ultimately place a limit on the robustness for use on 1H MRSI data. DMI data only contains natural abundance 2H lipid signals that were adequately removed with suppression factors below 10 (Figs. 2 and 3), thereby removing ambiguities in detecting elevated lactate levels.The basic SLIM algorithm as presented here for DMI can be modified and extended in several ways to enhance the immunity to signal heterogeneity and improve the reliability. Sub-division of the skull ROI can be optimized in terms of number of ROIs, ROI shapes and ROIs based on signal heterogeneity. Sub-division of the brain ROI can be beneficial, especially when aimed to extract 2H MR signals from clinically relevant ROIs such as tumor core and rim. Inclusion of B0 and B1 maps can remove magnetic field heterogeneity and can be obtained separately with MRI or extracted from the measured DMI data to increase the performance of SLIM.

The proposed lipid signal removal strategy is a significant step in the overall goal of making DMI a robust metabolic imaging method viable in a clinical MR environment without expert user intervention.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded, in part, by NIH grant NIBIB R01-EB025840.References

1. De Feyter HM, Behar KL, Corbin ZA, Fulbright RK, Brown PB, McIntyre S, Nixon TW, Rothman DL, de Graaf RA. Deuterium metabolic imaging (DMI) for MRI-based 3D mapping of metabolism in vivo. Sci Adv 2018;4(8):eaat7314.

2. Liu Y, De Feyter HM, Fulbright RK, McIntyre S, Nixon TW, de Graaf RA. Interleaved Fluid-attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) MRI and Deuterium Metabolic Imaging (DMI) on human brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med 2022;88:28-37.

3. Hu X, Levin DN, Lauterbur PC, Spraggins T. SLIM: spectral localization by imaging. Magn Reson Med 1988;8:314-322.

4. Dong Z, Hwang JH. Lipid signal extraction by SLIM: application to 1H MR spectroscopic imaging of human calf muscles. Magn Reson Med 2006;55:1447-1453.

5. Adany P, Choi IY, Lee P. B0-adjusted and sensitivity-encoded spectral localization by imaging (BASE-SLIM) in the human brain in vivo. Neuroimage 2016;134:355-364.

Figures

Figure 1 – Spatial prior knowledge for skull-based lipid removal. (A) MRI and (B) binary brain/skull segmentation. (C) To accommodate spatial signal heterogeneity and satisfy the assumptions underlying SLIM, the skull ROI is sub-divided in 100-150 smaller ROIs (4-10 mL). (E) The ROI-specific MR spectra generated by SLIM are used to generate (F) a ‘skull-only’ DMI which is subtracted from (D) the original dataset to provide 3D DMI without contamination from extracranial lipids (see Figs. 2/3).