4057

Time-dependent diffusion in healthy adult human thigh muscle in a clinically feasible acquisition1Queen Square Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 22Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 3Medical Radiation Physics, National Physical Laboratory, London, United Kingdom, 4Developmental Imaging and Biophysics, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Muscle fibres are larger than axons with a complex hierarchical internal structure causing a decrease in the diffusion coefficient with diffusion time. Acquisition of larger field-of-view thigh-level images is challenged by increased distortion, higher B0 inhomogeneity, incomplete fat saturation and longer acquisition times. We optimised a protocol to study the time-dependence of diffusion indices in healthy human thigh muscle in a clinically feasible scan time. MD and FA showed strong time dependence but slight disparities from previous work in the calf, possibly due to differences in the musculature of the thigh, male/female ratio, or changes in the acquisition with optimisation.Introduction

Muscle fibres are much larger than white matter axons, a more common area of application of diffusion imaging, and have a complex hierarchical internal structure1. The hierarchical structure of muscle leads to a marked decrease in the observed diffusion coefficient with diffusion time, which has been demonstrated in mice2 and healthy adults, boys with Duchenne’s and age-matched controls in the calf3. Characterising the diffusion time dependence in larger field-of-view thigh-level images is challenged by increased distortion, higher B0 inhomogeneity, incomplete fat saturation and longer total acquisition time. We optimised a time-dependant diffusion acquisition protocol to study the time-dependence D(t) of diffusion indices in human thigh muscle in healthy volunteers in a clinically feasible scan time.Methods

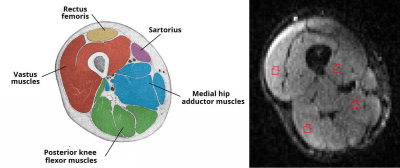

Six healthy adult volunteers (3 male, 3 female, average age 41, range 30-51 years) were imaged at 3T (MAGNETOM PrismaFit; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using a 36-channel peripheral-angiography leg coil with an 18-channel body coil to maintain signal coverage at thigh level. Volunteers were positioned feet first supine. Diffusion data were acquired using a prototype echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with a stimulated-echo (STEAM) preparation with diffusion-weighting gradient pulse duration (δ) 10 ms at 5 different diffusion times (Δ) (70, 130, 190, 270, 330 ms) for each acquiring 12 diffusion-gradient directions (equidistant on a sphere) at b-values of 0, 200, 400, and 600 s/mm2. A reversed phase-encoding volume at b-value 0 s/mm2 for image correction was also acquired. Acquisition time per Δ value was 5:16 mins with a total acquisition time of 26:20 mins for diffusion imaging. Voxel size was 2x2x4 mm3, TE 50 ms and TR 2800 ms, with Spectral Attenuated Inversion Recovery (SPAIR) fat suppression. Three-point Dixon images (gradient-echo TEs 3.45, 4.60, 5.75 ms, TR 101 ms, 1x1 mm2 pixels with slice thickness 1 mm) were acquired to provide anatomical reference images. Data were pre-processed using Tractor [http://www tractor-mri.org.uk/] and tensor fitting was performed at each diffusion time using FSL [https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/] using a weighted least-squares fit. Mean Diffusivity (MD), Fractional Anisotropy (FA) and principal eigenvectors were analysed in each voxel of interest. Regions of interest (ROIs) were then drawn on the b=0 s/mm2 (B0) images in the vastus, adductor and flexor muscles (Figure 1) with reference to the Dixon anatomical images. A simple t-test was used to demonstrate the difference in diffusion indices between 70 ms and 330 ms.Results

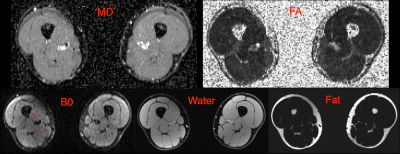

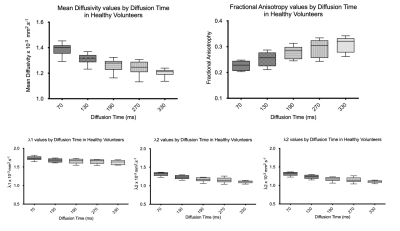

Example fat, water, B0, MD and FA images from one volunteer are shown in Figure 2. The B0 image shows good delineation of the muscle groups with acceptable distortion, although with incomplete fat suppression. Quantitative results are shown in Figure 3. The mean MD decreased from 1.39 x 10-3 mm2/s (SD ± 0.07 x 10-3 mm2/s) at Δ = 70 ms to 1.20 x 10-3 mm2/s (SD ± 0.09 x 10-3 mm2/s) at Δ = 330 ms. Mean FA increased from 0.23 (SD ± 0.03) at Δ = 70ms to 0.31 (SD ± 0.04) at Δ = 330 ms. Significance between the minimum and maximum diffusion times was P<0.0001 for MD and <0.0001 for FA.Discussion/Conclusion

We have successfully acquired time-dependent diffusion in the thigh in a clinically feasible scan duration. MD and FA show strong time dependence which is similar to our previous results in the calf in healthy adult volunteers4, there were however some differences in MD and FA (mean MD in the calf decreased from 1.31 x 10-3 mm2/s at Δ = 70 ms to 1.08 x 10-3 mm2/s at Δ = 330 ms and FA increased from 0.31 at Δ = 70 ms to 0.40 at Δ = 330 ms). This could be due to a difference in male/female ratio in the group, changes in the acquisition (12 directions were acquired in this work instead of 6) or differences in the musculature of the thigh to the calf. Further work to elucidate this is required.EPI distortion was not severe but sufficient that ROIs could not be drawn on the anatomical Dixon images and transferred directly to the diffusion images. The standard diffusion image correction methods of eddy and topup [https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/] failed, possibly due to the pseudo-cylindrical lower-limb anatomy being too different to the brain-oriented geometry FSL is optimised for. Future studies will focus on lower limb correction methods. Non-affine registration as an alternative to match anatomical and diffusion images would require further validation to ensure confident quantification.

Fat suppression in our data was not complete, visible EPI chemical shift artifact affecting peripheral parts of the vastus muscle and rectus femoris, but this did not affect the remaining thigh musculature which yielded useful data. A possible solution to this could be the use of fat saturation pads.

We expect this variable diffusion-time protocol to provide useful markers of microstructural change and pathology in neuromuscular diseases which can affect size, packing fraction and permeability of muscle fibres.

Acknowledgements

AM is funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. 179308). JT receives support from the UCLH NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.References

1. Feher J. Contractile Mechanisms in Skeletal Muscle. 2nd Edition ed: Elsevier; 2017.

2. Porcari P, Hall MG, Clark CA, Greally E, Straub V, Blamire AM. The effects of ageing on mouse muscle microstructure: a comparative study of time-dependent diffusion MRI and histological assessment. NMR in biomedicine 2018; 31(3).

3. McDowell AR, Feiweier T, Muntoni F, Hall MG, Clark CA. Clinically feasible diffusion MRI in muscle: Time dependence and initial findings in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2021.

4. McDowell AR, Hall MG, Feiweier T, Clark CA. Time-dependent diffusion in healthy human calf muscle in a clinically feasible acquisition time. 20th Annual meeting of ISMRM; 2020; Online; 2020.

Figures