4050

Safeguarded Deep Unfolding Network for Parallel MR Imaging1Medical AI Research Center, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Science, Shenzhen, China, 2Paul C. Lauterbur Research Center for Biomedical Imaging, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Science, Shenzhen, China, 3Pazhou Lab, Guangzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Image Reconstruction

This study proposes a safeguarded methodology for network unrolling. Specifically, focusing on parallel MR imaging, we unroll a zeroth-order algorithm, of which the network module represents a regularizer itself so that the network output can still be covered by a regularization model. Furthermore, inspired by the idea of deep equilibrium models, before backpropagation, we carry out the unrolled network to converge to a fixed point and then prove that it can tightly approximate the real MR image. In a case where the measurement data contain noise, we prove that the proposed network is robust against noisy interferences.Introduction

Recently, inspired by the tremendous success demonstrated by deep learning (DL), many studies have committed to applying DL to MR reconstruction (termed DL-MRI) and have achieved significant performance gains [1-6]. Particularly, [7] starts with a regularization model and resets the first-order information of the regularizer as learnable to unroll corresponding algorithms to deep networks[8-12]. Since the architecture of unrolled deep networks (UDNs) is driven by regularization models, it appears more explainable and predictable compared to data-driven networks. A large number of experiments have confirmed its competitiveness in reconstructed image quality.In theory, however, the following problems for UDNs are still not well studied. 1) Consistency: for the first-order (i.e., (sub)gradient or proximal operator) unrolled network module, there is no guaranteed functional regularizer whose first-order information matches it, which means that the output of the UDN is not consistent with the regularization models. In other words, the output of the UDN cannot inherit the explainable and predictable nature completely. 2) Convergence: although [13] showed that a first-order UDN with a nonexpansive constraint is guaranteed to converge to a fixed point, there is no theoretical guarantee that this fixed point is the solution of regularization models or a tight approximation of the real MR image. 3) Robustness: there is also no theoretical guarantee that existing UDNs are robust to noisy measurements. Furthermore [14] revealed that existing DL-MRI methods (including UDNs) typically yield unstable reconstruction, which severely hinders the clinical application of DL methods.

Methodology

In MRI, a forward model of parallel $k$-space data acquisition can be formulated as\begin{equation}\label{eq:1}y=\mathcal{M}{\widehat{x}}~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~(1)\end{equation}$$$\widehat{x},y\in\mathbb{C}^{N\times N_c}$$$, $$$N_c\geq1$$$ denotes the number of channels, $$$\widehat{x}$$$ is the full-sampled k-space data, $$$i$$$th column of which denotes the data acquired by the $$$i$$$th coil, $$$y$$$ is an undersampled measurement and $$$\mathcal{M}$$$ denotes the sampling pattern.SPIRiT [15] considers that every point in the grid can be linearly predicted by its entire neighborhood in all coils. Given this assumption, any k-space data $$$\widehat{x}_{i}$$$ at the $$$i$$$th coil can be represented by data from other coils with kernel $$$w_{i,n}$$$. Then, the k-space PI regularization model is:\begin{equation}\label{slr:1}\left\{\begin{aligned} \min_{\widehat{x}\in\mathbb{C}^{N\times N_c}} &R(\widehat{x}):=\sum_{i=1}^{N_c}\left\|\widehat{x}_i-\sum_{n=1}^{N_c}\widehat{x}_n\otimes{w_{i,n}}\right\|^2\\ \text{s.t.}~~&\mathcal{ M}\widehat{x}=y. \end{aligned}\right.~~~~~~~~~~~~(2)\end{equation}where $$$R$$$ is the so-called self-consistency regularizer. Algorithmically, the POCS is an effective zeroth-order algorithm for solving problem (2), which carries out the following updates:\begin{equation*}\left\{\begin{aligned} \widehat{x}_i^{k+\frac{1}{2}}&=\sum_{n=1}^{N_c}\widehat{x}_n^k\otimes{w_{i,n}}\\ \widehat{x}^{k+1}&=\mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{C}}(\widehat{x}^{k+\frac{1}{2}}) \end{aligned}\right.~~~~~~~~~~~~~(3)\end{equation*}where $$$\widehat{x}^{k}=[\widehat{x}_1^{k},\ldots,\widehat{x}_{N_c}^{k}]$$$ and $$$\mathcal{C}=\{\widehat{x}\in\mathbb{C}^d|\mathcal{M}\widehat{x}=y\}$$$. Looking closely at the above iterations, we can see that the POCS algorithm only calls the zeroth-order information of regularizer $$$R$$$ and does not call higher-order information. Leveraging the idea of a UDN, we release the linear convolution kernel (1-convolutional layer) in $$$R$$$ as a learnable multilayer CNN module $$$\Phi_{\phi}$$$ with parameters $$$\phi$$$ and train it in an end-to-end fashion. In particular, the recursion of the unrolled POCS algorithm is:\begin{equation}\label{gpocs}\left\{\begin{aligned} \widehat{x}^{k+\frac{1}{2}}&=\Phi_{\phi}({x}^k)\\ \widehat{x}^{k+1}&=\mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{C}}(\widehat{x}^{k+\frac{1}{2}}). \end{aligned}\right.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~(4)\end{equation}Specifically, the unrolled POCS (\ref{gpocs}) can be summed up as a zeroth-order algorithm for solving the following generalized PI regularization model:\begin{equation}\label{slr:1:1}\left\{\begin{aligned} \min_{\widehat{x}\in\mathbb{C}^{N\times N_c}} &R(\widehat{x}):=\|\widehat{x}-\Phi_{\phi}(\widehat{x})\|^2_F\\ \text{s.t.}~~&\mathcal{ M}\widehat{x}=y. \end{aligned}\right.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~(5)\end{equation}That is, the output of (4) can completely inherit the explainable and predictable nature of model (5). (5) is a generalization of the SPIRiT model (2), of which the linear predictable prior is extended to nonlinear predictability.

In particular, the network structure is shown in Fig. 1, and network training and testing are shown in Fig. 2.

Theoretical Results

Theorem 1: (Convergence) Suppose that $$$\Phi_{\phi_{i}}$$$ is $$$L$$$-Lipschitz continuous with $$$0<L<1$$$. The unrolled POCS (4) in Algorithms 1 and 2 converges to a fixed point globally.Theorem 2: (Stability) Suppose that $$$\Phi_{\phi_{i}}$$$ is $$$L$$$-Lipschitz continuous with $$$0<L<1$$$. When the measurement data contain noise, the noise in the reconstruction result of our method is amplified by a factor of up to $$$1/(1-L)$$$.

Experimental Results

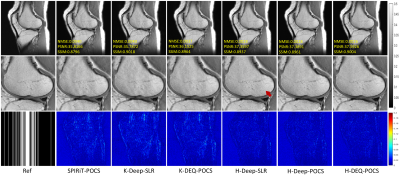

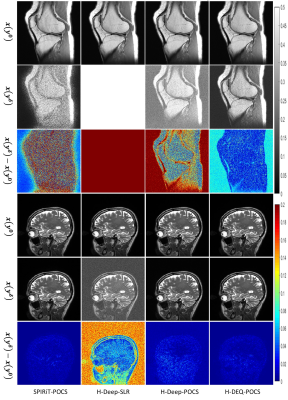

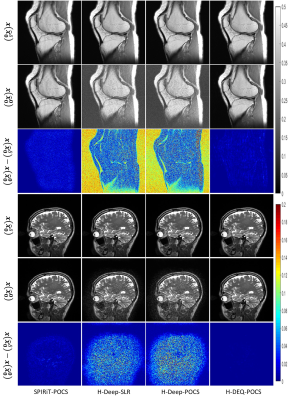

In this section, we test our proposed DEQ-POCS with k-space and hybrid architectures depicted in Figure 1, dubbed K-DEQ-POCS and H-DEQ-POCS for short, on the knee and brain datasets. To demonstrate the effectiveness of our methods, a series of extensive comparative experiments were studied. In particular, we compared the traditional k-space PI method (SPIRiT-POCS ) and SOTA k-space first-order UDN, i.e., Deep-SLR, based on k-space and hybrid architectures, dubbed K-Deep-SLR and H-Deep-SLR. In addition, we also compared the unrolled POCS (4) without convergent (DEQ) restriction, dubbed Deep-POCS, as an ablation study. We verified the accuracy, convergence and stability of the proposed method for reconstruction, and the corresponding results are shown in Figures 3-5.Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant No. 2020YFA0712200; the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 61771463, 81830056, U1805261, 61671441, 81971611, 12026603, 62106252 and 62206273.References

[1] S. Wang, Z. Su, L. Ying, X. Peng, S. Zhu, F. Liang, D. Feng, andD. Liang, “Accelerating magnetic resonance imaging via deep learning,”in 2016 IEEE 13th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging(ISBI), 2016, pp. 514–517.

[2] D. Liang, J. Cheng, Z. Ke, and L. Ying, “Deep magnetic resonance image reconstruction: Inverse problems meet neural networks,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 141–151, 2020.

[3] W. Huang, Z. Ke, Z.-X. Cui, J. Cheng, and D. Liang, “Deep low-rank plus sparse network for dynamic mr imaging,” Medical Image Analysis, p. 102190, 2021.

[4] J. Cheng, Z.-X. Cui, W. Huang, Z. Ke, L. Ying, H. Wang, Y. Zhu, and D. Liang, “Learning data consistency and its application to dynamic mr imaging,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 40, no. 11, pp.3140–3153, 2021.

[5] Z. Ke, W. Huang, Z.-X. Cui, J. Cheng, S. Jia, H. Wang, X. Liu, H. Zheng,L. Ying, Y. Zhu, and D. Liang, “Learned low-rank priors in dynamic mr imaging,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, pp. 1–1, 2021.

[6] Z. Ke, Z.-X. Cui, W. Huang, J. Cheng, S. Jia, L. Ying, Y. Zhu, and D. Liang, “Deep manifold learning for dynamic mr imaging,” IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging, pp. 1–1, 2021.

[7] K. Gregor and Y. LeCun, “Learning fast approximations of sparse cod-ing,” in Proceedings of International Conference on Machine Learning,2010, pp. 399–406.

[8] J. Adler and O.Öktem, “Learned primal-dual reconstruction,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1322–1332, 2018.

[9] K. Hammernik, T. Klatzer, E. Kobler, M. P. Recht, D. K. Sodickson,T. Pock, and F. Knoll, “Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated mri data,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 79, no. 6,pp. 3055–3071, 2018.

[10] M. Akc¸akaya, S. Moeller, S. Weingärtner, and K. Uˇ gurbil, “Scan-specific robust artificial-neural-networks for k-space interpolation (raki)reconstruction: Database-free deep learning for fast imaging,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 81, no. 1, pp. 439–453, 2019.

[11] T. H. Kim, P. Garg, and J. P. Haldar, “Loraki: Autocalibrated recurrent neural networks for autoregressive mri reconstruction in k-space,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09390, 2019.

[12] A. Pramanik, H. K. Aggarwal, and M. Jacob, “Deep generalization of structured low-rank algorithms (deep-slr),” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 39, no. 12, pp. 4186–4197, 2020.

[13] D. Gilton, G. Ongie, and R. Willett, “Deep equilibrium architectures for inverse problems in imaging,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.07944v1,2021.

[14] V. Antun, F. Renna, C. Poon, B. Adcock, and A. C. Hansen, “On instabilities of deep learning in image reconstruction and the potential costs of ai,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117,no. 48, pp. 30088–30095, 2020

[15] M. Lustig and J. M. Pauly, “Spirit: Iterative self-consistent parallel imaging reconstruction from arbitrary k-space,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 64, no. 2, pp. 457–471, 2010.

Figures

For training we carry out the unrolled POCS algorithm (4) to find a fixed point first and then update the network parameters $$$\phi$$$ by a certain optimizer with respect to the loss function $$$\ell(\mathring{\widehat{x}}^m,\widehat{x}^m)$$$. Note that to find the fixed point faster, we can use the Anderson algorithm to accelerate the unrolled POCS algorithm (4).

The testing process for the DEQ-POCS network is depicted in Algorithm 2. Insert the trained $$$\Phi_{\phi_{KM}}$$$ into the unrolled POCS algorithm (4) and execute it to converge to a fixed point.

Ideally, the selection of the initial input has little effect on the final solution for convergent algorithms.To verify the convergence of our method, in this experiment, we test various methods against interferences on the initial input. We can observe that the noisy initial input has very little influence on the performances of the traditional SPIRiT-POCS algorithm and our H-DEQ-POCS. This experimental result confirms the convergence property of the proposed H(K)-DEQ-POCS and reveals that the general UDN generally cannot reach convergence.