4026

Default Mode Network is Not Related to Similarly Vigilance Dependent Slow Rhythms1Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI (resting state), Brain Connectivity

Several studies point to brain slow rhythms as the basis of rsfMRI signal. We recently reported that only vigilance/arousal dependent components of fMRI signal that are not specific to brain function networks (BFNs) decrease after suppression of slow rhythms, while BFNs increase in apparent strength. Default mode network (DMN) is a BFN that exhibits similar dependence on vigilance as slow rhythms. In this study, we examined the effects of slow rhythm suppression on the integrity of DMN. Our results show that DMN is not related to these rhythms and behaves just like other BFNs upon their suppression.INTRODUCTION

The neurophysiological basis underlying resting state fMRI (rsfMRI) signals are not completely understood, impeding accurate interpretation of rsfMRI studies. A number of studies [1, 2] point to slow rhythms (0.1-2 Hz) as the basis of rsfMRI signal. Slow rhythms exist in the absence of stimulation, propagate across the cortex [3], and are strongly modulated by vigilance [4] similar to parts of rsfMRI signals [5, 6] like quasi-periodic patterns (QPPs). These QPPs can complicate the estimation of functional connectivity (FC) via rsfMRI, either by existing as unmodeled signal or by inducing additional wide-spread correlation between voxel-time courses of functionally connected brain regions. However, unlike slow rhythms, the strength of FC in brain function resting state networks (RSNs) decreases with reductions in vigilance and arousal levels [7, 8]. We recently reported that putative suppression of slow rhythms suppresses QPPs [9]. This in turn enhances the detectability of canonical brain function networks by removing these signals from the rsfMRI data [9]. Default mode network (DMN) is a critical brain function network that exhibits similar dependence on vigilance [10] as QPPs and slow rhythms. If DMN is also diminished after suppression of slow rhythms, it would indicate that it is an artifact of these rhythms, which would upend current theories of brain function. In this study, we examined the effects of slow rhythm suppression on the integrity of DMN.METHODS

Slow rhythms are generated through interplay between cortico-cortical and thalamocortical rhythm generators. The thalamocortical generators are sustained by bursting activity in thalamic T-type calcium channels (TTCCs)[11]. In this study, slow rhythms were attenuated through administration of a selective TTCC blocker, TTA-P2 according to well-established methods [11]. All experiments were conducted with protocols approved by IACUC. Seven adult Sprague-Dawley rats were administered subcutaneous injections of TTA-P2 (3-6 mg/kg dissolved in vehicle (4% DMSO saline solution)), immediately before and after 40-90 min fMRI scans obtained under sedation induced by dexmedetomidine (which does not interfere with the action of TTA-P2 [12]). Five other rats were administered the vehicle. The effects of TTA-P2/vehicle on DMN was assessed by examining the last 40 min of the Baseline session and the first 40 min of the TTA-P2/vehicle session, in order to examine the same length of data across all rodents. MRI data were acquired on a 9.4 T Bruker animal MRI system with a custom-built surface coil. RsfMRI scans were obtained with a whole-brain respiration-gated gradient echo EPI (TR/TE/FA = 2000ms/25ms/90°, resolution = 0.5 mm isotropic voxels). Data was preprocessed with standard pipelines [13, 14], band-passed filtered (0.01-0.20 Hz) and aligned to Paxinos atlas space [15, 16]. The strength of DMN was assessed by examining the FC between different nodes of DMN (10), quantified by Pearson correlation between corresponding Paxinos atlas ROI-averaged rsfMRI time-series. Group analysis was conducted through between-session (TTA-P2 vs Baseline) paired t-tests on the z-transformed correlation coefficients of different intra-DMN connections as well as their mean.RESULTS & DISCUSSION

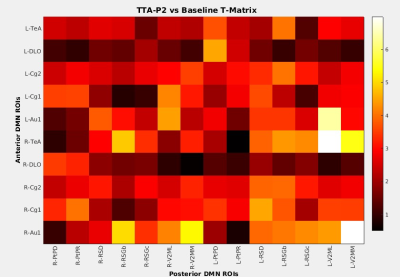

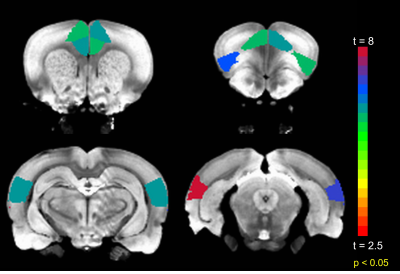

Anterior to posterior DMN connections are optimal for this investigation as they are the first to be compromised after sedation (11). The mean FC among all such connections significantly (p < 0.001) increased after TTA-P2 injection. Figure 1 shows the matrix of TTA-P2 vs Baseline t-scores of all anterior to posterior DMN connections. FC of 81/140 connections significantly (p < 0.05) increased after TTA-P2 administration. Retrosplenial cortex, which is the strongest hub of DMN in rats (10) exhibited (Figure 2) significant increase in FC to all anterior DMN connections. Vehicle had no appreciable effect on intra-DMN FC. TTA-P2 administration increased apparent FC in DMN, in contrast to QPPs which decreased in strength after TTA-P2 [9]. Thus, even though DMN increases in strength with decreasing vigilance like slow rhythms, suppression of these rhythms increases the strength of DMN like other canonical brain function networks examined in our last study [9].CONCLUSION

These results indicate that DMN is indeed a canonical brain function network, even though it exhibits similar dependence on vigilance as slow rhythms. DMN behaves just like other cognitive brain function networks and has a similar neural basis.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant NINDS 1R21NS122013-01A1 (PI: Gopinath/Keilholz).References

1. Chan, R.W., et al., Low-frequency hippocampal-cortical activity drives brain-wide resting-state functional MRI connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017.

2. Matsui, T., T. Murakami, and K. Ohki, Transient neuronal coactivations embedded in globally propagating waves underlie resting-state functional connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(23): p. 6556-61.

3. Sheroziya, M. and I. Timofeev, Global intracellular slow-wave dynamics of the thalamocortical system. J Neurosci, 2014. 34(26): p. 8875-93.

4. Steriade, M., Corticothalamic resonance, states of vigilance and mentation. Neuroscience, 2000. 101(2): p. 243-76.

5. Billings, J.C.W. and S.D. Keilholz, The Not-So-Global BOLD Signal. Brain Connect, 2018.

6. Thompson, G.J., et al., Short-time windows of correlation between large-scale functional brain networks predict vigilance intraindividually and interindividually. Hum Brain Mapp, 2013. 34(12): p. 3280-98.

7. Hutchison, R.M., et al., Isoflurane induces dose-dependent alterations in the cortical connectivity profiles and dynamic properties of the brain's functional architecture. Hum Brain Mapp, 2014.

8. Larson-Prior, L.J., et al., Cortical network functional connectivity in the descent to sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(11): p. 4489-94.

9. Khalilzad Sharghi, V., et al., Selective blockade of rat brain T-type calcium channels provides insights on neurophysiological basis of arousal dependent resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging signals. Front Neurosci, 2022. 16: p. 909999.

10. Raichle, M.E., et al., A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2001. 98(2): p. 676-82.

11. David, F., et al., Essential thalamic contribution to slow waves of natural sleep. J Neurosci, 2013. 33(50): p. 19599-610.

12. Horvath, G., et al., Drugs acting on calcium channels modulate the diuretic and micturition effects of dexmedetomidine in rats. Life Sci, 1996. 59(15): p. 1247-57.

13. Majeed, W., et al., Spatiotemporal dynamics of low frequency BOLD fluctuations in rats and humans. Neuroimage, 2011. 54(2): p. 1140-50.

14. Pan, W.J., et al., Resting State fMRI in Rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci, 2018. 83(1): p. e45.

15. Paxinos, G. and C. Watson, Paxino's and Watson's The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Seventh edition. ed. 2014, Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier/AP, Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier. 1 volume (unpaged).

16. Valdes-Hernandez, P.A., et al., An in vivo MRI Template Set for Morphometry, Tissue Segmentation, and fMRI Localization in Rats. Front Neuroinform, 2011. 5: p. 26.