4023

Behavioural Relevance modulates BOLD-fMRI responses in the rat Visual Cortex1Champalimaud Research, Champalimaud Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI, Multimodal, NEURO

Neuronal responses are shaped by experiences. Plasticity can occur at single neuron level or at the full population level. Here, we established a novel behavioural task requiring rats to distinguish between continuous and flickering lights. We then performed fMRI in trained vs naive animals and investigated BOLD-fMRI responses along the visual pathway. When light flashes become meaningful in trained animals, the BOLD activation patterns are significantly modulated compared to naive counterparts, in particular in higher visual cortex and associative areas. BOLD-fMRI signals are thus capable of deciphering plasticity arising from strong associations with actions and rewards.Introduction

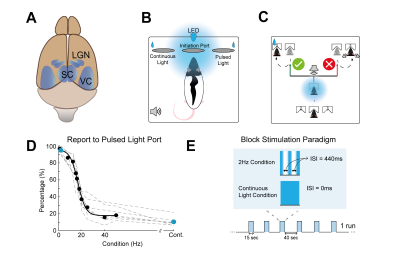

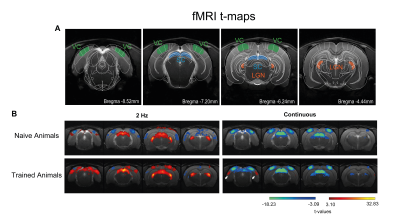

Neuroplasticity is a multifaceted process that occurs during development, upon learning, and in response to injury and loss of function. In humans, changes in BOLD-fMRI signals upon learning have been reported1,2 but their underlying mechanisms are not well understood. In rodents, neuroplasticity is typically studied using fMRI in animal models of development, enrichment3 or disease, where effects are large4,5. However, neuronal responses can be strongly modulated when stimuli become behaviourally relevant6-9 and detecting learning-induced fMRI modulations in rodents could be paramount for better understanding the mechanisms underpinning neuroplasticity as well as for following these processes noninvasively over time.In recent work, flashing lights with decreasing Inter Stimulus Intervals (ISIs) drove a transition from positive to negative BOLD responses (PBRs and NBRs) in the rat visual pathway10 (Fig. 1A), which reflected an attenuation of visually evoked potentials in the visual cortex (VC) and superior colliculus (SC). Here, we hypothesized that this paradigm can be used to infer on whether such activation/suppression signals could be affected by experience. To this end, we designed a novel task and trained animals to discriminate flashing from continuous light (Fig1.B&C), thus creating an association between the stimuli and actions/reward (Fig1D). We then ask whether this training affects the BOLD-fMRI signals in the brain.

Methods

Animal experiments were pre-approved by institutional and national authorities and were carried out according to European Directive 2010/63.Behaviour: Water-deprived rats had to poke in the central port of a behavioural box (Fig1A) to initiate a continuous or a flickering blue LED. After 1sec, a pure-tone was played (10KHz) signaling the response time-window. Correct choices were rewarded with water and incorrect choices were penalized with a timeout and a burst of noise (Fig.1E).

Animal Preparation for MRI: Adult Long-Evans rats were sedated with medetomidine; temperature and respiration rate were monitored.

MRI experiments: A 9.4T BioSpec scanner (Bruker, Germany) with an 86mm quadrature resonator for transmittance and a 4-element array cryoprobe11,12 for signal reception was used. fMRI data was acquired under 95%O2 with a SE-EPI sequence (TE/TR=40/1500ms, FOV=18x16.1mm2, resolution=268x268μm2, slice thickness=1.5mm, tacq=6min 45s).

Stimulation: A blue LED (𝜆=470nm) was used for binocular stimulation with ISI=490ms, and continuous light. The stimulation paradigm shown in Fig.1E.

Data analysis: fMRI pre-processing included manual outlier correction; slice-timing correction; smoothing (3D Gaussian kernel, FWHM=0.268mm isotropic); mean volume realignment and co-registration to the T2-weighted anatomical reference. GLM was performed using an HRF peaking at 1sec. A minimum significance level of 0.001 (FDR corrected) with a minimum cluster size of 20 voxels were used.

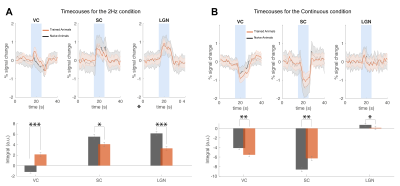

Atlas-based13 ROIs were manually drawn and signal time courses were detrended. The integral under the BOLD time courses during stimulation period were calculated and compared.

Results

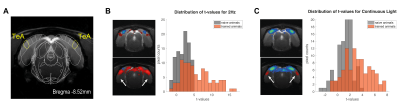

Our behavioural paradigm successfully elicited learning and after training, animals were capable of discriminating between a stimulus flashing at 2Hz and continuous light with very high success rates (Fig.1D). We then scanned trained vs. naïve animals that did not undergo any training. For the flashing 2Hz stimulus, naive animals exhibited little cortical involvement (Fig. 2B(top)). Strikingly, trained animals exhibited much stronger BOLD responses in the cortex Fig. 2B(bottom). For the continuous light condition, where cortical suppression takes place, the expected NBRs were observed both for the naïve and the trained groups. Strikingly however, clear PBRs were observed in the trained group in more lateral cortex (white arrows in the Fig.2B), identified as the TeA. An ROI analysis (Fig.3A) confirmed these trends and showed that the largest differences between the groups occur at the cortical level, while the other junctions along the pathway show similar BOLD curves. A simple quantification of these effects (Fig3B-D) also confirmed these trends; and we show that a distribution of t-values for TeA exhibits a positive shift when the animals are trained (Fig.4).Discussion

Perceptual-learning alters neuronal responses to stimuli at single cell and population level for somatosensory, auditory and visual cortices, as well as higher associative-areas6-9. Our findings clearly reveal differences in BOLD-fMRI activity along the visual pathway between the trained and naïve groups6-9 (Figs2&3), mainly in VC, with the largest differences for the lower frequency presented (Fig3). As the cortex is important for learned behaviours and responds mainly to lower frequencies10, our findings support the hypothesis of learning-induced plasticity in this model. The power and added-value of fMRI is demonstrated in this study by mapping the brain-wide responses, thereby enabling the discovery of the involvement of associative areas14-17 in the visual task. Indeed, the now meaningful flashes elicited responses in higher associative areas, mainly in Temporal Association Cortex (TeA), which is not usually activated during naive visual processing (Fig.4B&C). This likely indicates that these areas actively participate in neural computations during learning14,18-21. and potentially encode lower-level visual characteristics or predicted values associated with visual stimulus22,23 after learning.Conclusions

Modulation of BOLD responses following perceptual learning were investigated. Cortical BOLD responses became stronger for low frequencies and results also show activation of higher associative cortex TeA. These data suggest behavioural relevance of stimuli can cause visible changes to BOLD responses even for simpler stimuli.Acknowledgements

The first and second authors contributed equally to the presented work.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Cristina Chavarrías for the implementation of the fMRI in the acquisition MRI sequences and Ms. Francisca Fernandes for the fMRI analysis MATLAB code which was used for the generation of the BOLD t-maps.

References

[1] Herdener, Marcus, et al. "Musical training induces functional plasticity in human hippocampus." Journal of Neuroscience 30.4 (2010): 1377-1384.

[2] Garvert, Mona M., et al. "Learning-induced plasticity in medial prefrontal cortex predicts preference malleability." Neuron 85.2 (2015): 418-428.

[3] Zhang, Tie-Yuan, et al. "Environmental enrichment increases transcriptional and epigenetic differentiation between mouse dorsal and ventral dentate gyrus." Nature communications 9.1 (2018): 1-11.

[4] Dijkhuizen, Rick M., et al. "Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reorganization in rat brain after stroke." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98.22 (2001): 12766-12771.

[5] Pelled, Galit, et al. "Ipsilateral cortical fMRI responses after peripheral nerve damage in rats reflect increased interneuron activity." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106.33 (2009): 14114-14119.

[6] Yang, T., & Maunsell, J. H. (2004). The effect of perceptual learning on neuronal responses in monkey visual area V4. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(7), 1617-1626.

[7] Viswanathan, P., & Nieder, A. (2015). Differential impact of behavioral relevance on quantity coding in primate frontal and parietal neurons. Current Biology, 25(10), 1259-1269.

[8] Lee, T. S., Yang, C. F., Romero, R. D., & Mumford, D. (2002). Neural activity in early visual cortex reflects behavioral experience and higher-order perceptual saliency. Nature neuroscience, 5(6), 589-597.

[9] Recanzone, G. H., Schreiner, C. E., & Merzenich, M. M. (1993). Plasticity in the frequency representation of primary auditory cortex following discrimination training in adult owl monkeys. Journal of Neuroscience, 13(1), 87-103.

[10] Gil, R.; F. Fernandes, F.; Shemesh, N.; Increased negative BOLD responses along the rat visual pathway with short inter-stimulus intervals [abstract]. In: 2020 ISMRM and SMRT Annual Meeting and Exhibition; 08-14 August 2020; Virtual conference

[11] Niendorf, Thoralf, et al. "Advancing cardiovascular, neurovascular and renal magnetic resonance imaging in small rodents using cryogenic radiofrequency coil technology." Frontiers in pharmacology 6 (2015): 255;

[12] Baltes, Christof, et al. "Micro MRI of the mouse brain using a novel 400 MHz cryogenic quadrature RF probe." NMR in Biomedicine: An International Journal Devoted to the Development and Application of Magnetic Resonance In vivo22.8 (2009): 834-842;

[13] Paxinos, George, and Charles Watson. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates: hard cover edition. Elsevier, 2006;

[14] Gold, J. I., & Shadlen, M. N. (2007). The neural basis of decision making. Annual review of neuroscience, 30(1), 535-574.

[15] Briggs, F. (2020). Role of feedback connections in central visual processing. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci, 6, 313-334.

[16] Bullier, J., Hupé, J. M., James, A. C., & Girard, P. (2001). The role of feedback connections in shaping the responses of visual cortical neurons. Progress in brain research, 134, 193-204.

[17] Kar, Kohitij, and James J. DiCarlo. "Fast recurrent processing via ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is needed by the primate ventral stream for robust core visual object recognition." Neuron 109.1 (2021): 164-176.

[18] Roitman, J. D., & Shadlen, M. N. (2002). Response of neurons in the lateral intraparietal area during a combined visual discrimination reaction time task. Journal of neuroscience, 22(21), 9475-9489.

[19] Shadlen, M. N., & Newsome, W. T. (2001). Neural basis of a perceptual decision in the parietal cortex (area LIP) of the rhesus monkey. Journal of neurophysiology, 86(4), 1916-1936.

[20] Romo, R., Hernández, A., Zainos, A., Lemus, L., & Brody, C. D. (2002). Neuronal correlates of decision-making in secondary somatosensory cortex. Nature neuroscience, 5(11), 1217-1225.

[21] Hanks, T. D., Kopec, C. D., Brunton, B. W., Duan, C. A., Erlich, J. C., & Brody, C. D. (2015). Distinct relationships of parietal and prefrontal cortices to evidence accumulation. Nature, 520(7546), 220-223.

[22] Tasaka, G. I., Feigin, L., Maor, I., Groysman, M., DeNardo, L. A., Schiavo, J. K., ... & Mizrahi, A. (2020). The temporal association cortex plays a key role in auditory-driven maternal plasticity. Neuron, 107(3), 566-579.

[23] Ramesh, Rohan N., et al. "Intermingled ensembles in visual association cortex encode stimulus identity or predicted outcome." Neuron 100.4 (2018): 900-915

Figures

Figure4: A. Example anatomical scans with overlayed atlas scheme for the TeA region. B. Left - Comparison of BOLD maps for the Naive and Trained cohorts for the slices containing the TeA region, during 2Hz stimulation; Right - histograms of the distribution of t-values in the TeA ROI for naive and trained animals. C. same as B. but for the Continuous light regime. Naive cohort is shown in grey and trained cohort in orange.