4022

Whole-brain fMRI study of mice under medetomidine/ketamine anesthesia to identify brain regions activated by musk odors1Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan

Synopsis

Keywords: New Devices, Preclinical

Muscone, a major component of musk odor, attracts male mice. The odor-evoked behaviors are mediated by neural circuits activated by the stimulation. We have been working on whole-brain BOLD fMRI studies of mice, using a method that employs periodic odor stimulation and independent component analysis. In this study, we investigated the brain regions activated by muscone in mice under medetomidine and low-dose ketamine anesthesia. Ketamine reportedly exhibits disinhibition of glutamate signaling at a low dose. As the result, we identified numerous muscone-evoked activated regions located in the olfactory pathways and higher-order regions in the cerebrum.Introduction

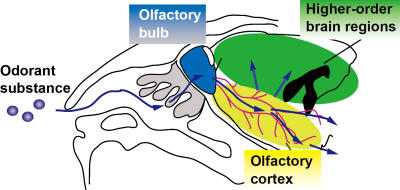

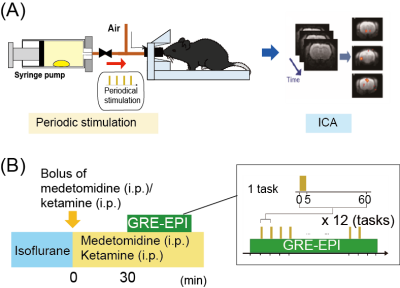

Musk odor is used in fragrances and perfumes and muscone is its major compound1. Interestingly, while muscone is derived from musk deer, it attracts male mice2. To understand how muscone induces the attraction behaviors for mice, the neural circuits activated by muscone must be elucidated. Olfaction starts from the binding of odorant substance to specific olfactory receptors, and then the signal is transduced to the olfactory bulb. Subsequently, the signals are relayed to the brain regions of the olfactory cortex, and then further transduced to higher-order brain regions in the cerebrum (Fig. 1). To elucidate the signal transduction pathways in the brain, BOLD fMRI is the method of choice. Indeed, odor-evoked activations in the mouse olfactory bulb were successfully detected by a BOLD fMRI study3. However, other brain regions in the cerebrum must be examined to identify the activated brain regions responsible for the behaviors. To address this issue, we employed the BOLD-ICA method, which combines periodic odor stimulation and independent component analysis (ICA)4. Odor stimulations are applied at constant intervals, using an automated odor stimulation system5. As a result, BOLD-derived signal increases occur periodically, and the signals are detected by the ICA method as task-relevant components (Fig. 2A)4. One problem is that the anesthetics used with mice influence the neural activations. Recently, a BOLD fMRI study of mice anesthetized with medetomidine and low-dose ketamine was reported6. Since a low dose of ketamine reportedly exhibits disinhibition of the olfactory pathways,6 we speculated that, by using the ketamine anesthesia, it would become possible to identify muscone-evoked neural activations that are otherwise difficult to detect. In this study, we sought to identify the brain regions activated by muscone, and for comparison isoamyl acetate (IAA), in mice under the medetomidine/ketamine anesthesia.Methods

An automated odor stimulation system (in collaboration with an ARCO SYSTEM) was used to apply the odor to mice in a strictly periodic manner5. The experimental design is shown in Fig. 2B. In this system, a drop of muscone solution was placed in a 50 mL syringe to fill it with muscone vapor. The syringe pump was then automatically operated to infuse the saturated vapor into the noses of the mice. MRI experiments were performed with a 7.0 Tesla Bruker BioSpec 70/20 scanner and a mouse brain 2-channel phased array surface cryogenic coil (Bruker BioSpin). Mice (male C57BL/6, 8–10 weeks old) were anesthetized with 2.0% isoflurane and then secured on the MRI cradle. A bolus of medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg) and ketamine (8 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally. The medetomidine and ketamine were then intraperitoneally infused at 0.05 mg/kg/h and 16 mg/kg/h, respectively. At 30 min after the bolus injection, the GRE-EPI image acquisition was started: TR/TE = 2000/21.4 ms; FOV = 1.92×1.92 cm2; matrix = 96×96; resolution = 200×200 µm2; slice thickness = 400 µm; number of slices = 22; NEX = 1; flip angle = 70°. During the experiment, muscone vapor was applied for 5 sec at 1 min intervals, and this task was repeated 12 times (Fig. 2B). Data from multiple mice (n=9, muscone; n=4, IAA) were combined and analyzed by group ICA. The scanned functional data were registered to a template7,8 and subjected to the group ICA method, using the FSL (FMRIB Software Library; www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) program. Signal transition components at the 16.7 mHz frequency were selected as the stimulation-relevant activations, and then positive components were manually selected.Results

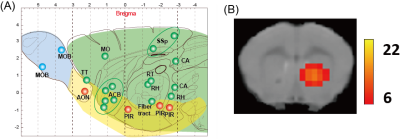

We applied the BOLD-ICA method for male mice stimulated by muscone or IAA. In the case of mice stimulated by muscone, numerous activated brain regions were detected. The identified regions were distributed over the whole brain, including olfactory bulb, olfactory cortex and other regions in the cerebrum (Fig. 3A). In the case of mice stimulated by IAA, activated brain regions were also distributed over the whole brain (data not shown). A comparison between the muscone and IAA stimulations revealed that the brain regions of the olfactory conduction pathways (i.e., the olfactory bulb, piriform cortex) were activated in both cases. In contrast, numerous muscone-specific activated regions were identified. For example, the nucleus accumbens was activated only in the case of muscone stimulation (Fig. 3B).Discussion

In this study, muscone- and IAA-evoked activated brain regions were identified in mice under medetomidine and low-dose of ketamine anesthesia by the BOLD-ICA method. In the case of mice stimulated by muscone, the brain regions identified in the olfactory bulb and olfactory cortex were roughly consistent with a previously performed analysis monitoring the c-Fos protein expression9. In addition, the nucleus accumbens was identified as a muscone-specific activated brain region. As the nucleus accumbens is associated with the reward system, it is potentially associated with behaviors evoked by odor stimulations.Conclusion

We detected brain regions activated by muscone and IAA in male mice under medetomidine and low-dose ketamine anesthesia by the BOLD-ICA method. In both cases, the identified brain regions were distributed over the whole brain, including the olfactory bulb, olfactory cortex and other regions in the cerebrum. We also detected muscone-specific activated brain regions.Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Mika Shirasu and Prof. Kazushige Touhara (The University of Tokyo) for fruitful discussion.References

1. Touhara K, Vosshall LB. Sensing odorants and pheromones with chemosensory receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:307–332.

2. Horio N, et al. Contribution of individual olfactory receptors to odor-induced attractive or aversive behavior in mice. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:209.

3. Xu F, et al. Odor maps of aldehydes and esters revealed by functional MRI in the glomerular layer of the mouse olfactory bulb. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11029–11034.

4. Funatsu H, et al. A BOLD analysis of the olfactory perception system in the mouse whole brain, using independent component analysis. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2017;25:5363.

5. Hayashi F, et al. Odor stimulation by automated syringe pumps in combination with independent component analysis for BOLD-fMRI study of mouse whole brain. Proc Intl. Soc Mag Reson Med. 2019;27:3685.

6. Zhao F, et al. fMRI study of olfactory processing in mice under three anesthesia protocols: Insight into the effect of ketamine on olfactory processing. NeuroImage. 2020;116725.

7. Hikishima K, et al. In vivo microscopic voxel-based morphometry with a brain template to characterize strain-specific structures in the mouse brain. Sci Rep. 2017;7:85.

8. Takata N, et al. Flexible annotation atlas of the mouse brain: combining and dividing brain structures of the Allen Brain Atlas while maintaining anatomical hierarchy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6234.

9. Shirasu M, et al. Olfactory receptor and neural pathway responsible for highly selective sensing of musk odors. Neuron. 2014;81:165–178.

Figures