4021

Pharmacological Inactivation of the Inhibitory Zona Incerta Decreased Resting-state Functional MRI Connectivity1Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China, 2Laboratory of Biomedical Imaging and Signal Processing, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China, 3Department of Diagnostic Radiology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China, 4School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI (resting state), Neuroscience

In the recent decade, resting-state functional MRI (rsfMRI) has emerged as the most invaluable, non-invasive imaging technique to map long-range, brain-wide functional connectivity networks. Despite the enormous potential inherent in this technique, our present knowledge of the neural underpinnings of rsfMRI connectivity remains generally incomplete given the lack of studies examining the role of the inhibitory neural population, which is the counterpart of the excitatory neurons. In this study, we directly examine the role of zona incerta, which is one of the major source of inhibitory drive to the cortex.INTRODUCTION

As part of the caudal prethalamus (formerly known as subthalamus)1, zona incerta (ZI) is widely connected to different cortical regions, especially the somatosensory and motor cortices2,3. It is one of the major sources of inhibitory inputs to the cortex and plays a significant role in sensory information coordination. Apart from the sensory cortical regions, ZI also projects to numerous other cognitive-related brain regions and has been associated with many behavioral functions, such as predation, feeding, pain, freezing response, and movement4-6. Research showed that optical silencing of ZI eliminated remote cortical inhibition10, which has been considered an essential component distributed across local brain circuits and large-scale brain networks for information processing14,15. Moreover, another study showed that spindle-like oscillations were evoked in ZI when stimulating the central thalamus, whereby feedforward thalamo-cortical inhibition is generated to evoke suppression in the cortex, suggesting strong inhibitory inputs to thalamo-cortical networks from ZI11. Given the widespread projections to the cortex, thalamus, midbrain, hypothalamus, pons, and medullary7, ZI has been postulated to greatly influence brain-wide functional connectivity8,9 but the extent of its influence and contribution remains unclear. In this study, we deployed resting-state functional MRI (rsfMRI) to examine changes in brain-wide functional connectivity when the neurons of zona incerta were pharmacologically inactivated with tetrodotoxin (TTX).MATERIALS AND METHOD

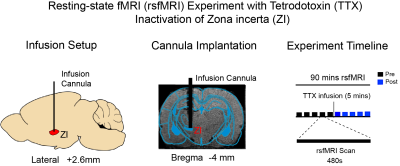

Animal preparation: Before conducting rsfMRI experiments, a glass cannula was first implanted into the left zona incerta (-4mm anterior/posterior, 2.6mm medial/lateral, and -7.2mm dorsal/ventral from Bregma, respectively; Figure 1) of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (~500g; 8~10 weeks old; N=4). RsfMRI experiments were subsequently conducted under 1.0% isoflurane.TTX infusion: 0.5μl 5ng/μl)16,17 TTX was delivered into the left ZI to deactivate the neurons in ZI. Typically, 5 rsfMRI scans were conducted before TTX is delivered to left ZI. TTX infusion lasts for 5 minutes. 5 rsfMRI scans were performed immediately after cessation of TTX infusion.

RsfMRI Data Acquisition: All data was acquired on a 7T Bruker scanner with a single-channel brain surface coil. RsfMRI data was acquired using a single-shot GE-EPI sequence with TR/TE = 750/20ms, FOV=32×32 mm2, 64×64 matrix and 16 contiguous 1-mm slices. High-resolution T2 image were acquired to show the site of injection in the zona incerta.

RsfMRI Data Analysis: GE-EPI images from each animal were realigned, co-registered to a T2 anatomical template, averaged across animals, smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 0.5mm FWHM and high-pass filtered (>128s) using SPM12. The group-averaged rsfMRI interhemispheric connectivity maps were generated by applying seed-based analysis (SBA)16,17. For SBA, two 3×3 voxel regions were chosen as the ipsilateral and contralateral seed, respectively, in the primary somatosensory (S1), secondary somatosensory (S2) and motor cortices (MC), superior colliculus (SC), primary auditory cortex (A1), cingulate cortex (Cg), and prelimbic cortex (PrL). Two-tail paired t-test were applied to compare the rsfMRI connectivity strength before and after TTX infusion.

RESULT

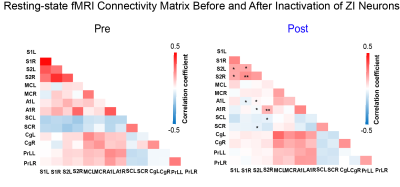

As expected, we observed robust interhemispheric rsfMRI connectivity at S1, S2, MC, SC, A1, Cg, and PrL during baseline conditions (i.e., before TTX infusion; Figure 2)16-19. Interhemispheric connectivity decreased significantly following TTX infusion across sensorimotor cortices (S1, S2, MC, A1, and SC; Figure 2). For inter-regional rsfMRI connectivity, the connectivity strength significantly declined in the sensorimotor network (Figure 3), specifically between S1&S2 (left hemisphere: 0.33±0.03 to 0.17±0.01, p<0.05; right hemisphere: 0.40±0.03 to 0.21±0.01, p<0.01), S1&A1 (left hemisphere: 0.08±0.01 to -0.04±0.01, p<0.05; right hemisphere: 0.16±0.02 to 0.05±0.03, p<0.058), S2&A1 (left hemisphere: 0.15±0.01 to 0.01±0.01, p<0.05; right hemisphere: 0.29±0.03 to 0.15±0.02, p<0.01), and S2&SC (left hemisphere: -0.14±0.01 to -0.05±0.01, p<0.053; right hemisphere: -0.15±0.01 to -0.08±0.01, p<0.058) after inactivation of left ZI neurons.DISSCUSION AND CONCLUSION

Our findings demonstrate that ZI plays a role in regulating brain-wide functional connectivity, particularly within the sensorimotor network. Inhibitory/GABAergic pathways7 such as the efferent pathways from ZI to the cortex has been shown to significantly modulate synchronous slow neural activities/oscillations12. Further, resting-state connectivity has long been shown to be associated with slow neural oscillations13. Neural oscillations at any specific brain region are dependent on balanced inhibitory and excitatory drive1. Our findings suggest that the deactivation of ZI neurons likely disrupted the expression of endogenous slow spontaneous neural oscillations due to the removal of inhibitory drive to the cortex11. However, further electrophysiological investigations are warranted to examine the changes in the underlying neural activities to better infer how they modulate rsfMRI connectivity. In conclusion, ZI plays an important role in neural information coordination in brain-wide functional connectivity, and deactivation of ZI via injecting TTX decreases resting-state cortical interhemispheric MRI functional connectivity.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Hong Kong Research Grant Council (HKU17112120, HKU17127121, HKU17127022 and R7003-19F to E.X.W., and HKU17103819, HKU17104020 and HKU17127021 to A.T.L.L.), Lam Woo Foundation, and Guangdong Key Technologies for AD Diagnostic and Treatment of Brain (2018B030336001) to E.X.W..References

1. Fratzl A, Hofer SB. The caudal prethalamus: Inhibitory switchboard for behavioral control? Neuron. 2022; 110(17):2728-2742.

2. Nicolelis MA, Chapin JK, Lin RC. Development of direct GABAergic projections from the zona incerta to the somatosensory cortex of the rat. Neuroscience. 1995; 65(2):609-31.

3. Chometton S, Barbier M, Risold PY. The zona incerta system: Involvement in attention and movement. Handb Clin Neurol. 2021;180:173-184.

4. Zhang X, van den Pol AN. Rapid binge-like eating and body weight gain driven by zona incerta GABA neuron activation. Science. 2017;356(6340):853-859.

5. Zhao ZD, Chen Z, Xiang X, et al. Zona incerta GABAergic neurons integrate prey-related sensory signals and induce an appetitive drive to promote hunting. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(6):921-932.

6. Chou XL, Wang X, Zhang ZG, et al. Inhibitory gain modulation of defense behaviors by zona incerta. Nat Commun. 2018; 9(1):1151.

7. Yang Y, Jiang T, Jia X, et al. Whole-Brain Connectome of GABAergic Neurons in the Mouse Zona Incerta. Neurosci Bull. 2022.

8. Lee JH, Liu Q, Dadgar-Kiani E. Solving brain circuit function and dysfunction with computational modeling and optogenetic fMRI. Science. 2022; 378(6619):493-499.

9. Michel T, Stephanie J. The Emergent Properties of the Connected Brain. Science. 2022; 378(6619):505-510

10. Weitz AJ, Lee HJ, Choy M, et al. Thalamic Input to Orbitofrontal Cortex Drives Brain-wide, Frequency-Dependent Inhibition Mediated by GABA and Zona Incerta. Neuron. 2019;104(6):1153-1167.e4.

11. Liu J, Lee HJ, Weitz AJ, et al. Frequency-selective control of cortical and subcortical networks by central thalamus. Elife. 2015; 4:e09215.

12. Dienel SJ, Lewis DA. Alterations in cortical interneurons and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis. 2019; 131:104208.

13. Chuang KH, Nasrallah FA. Functional networks and network perturbations in rodents. Neuroimage. 2017; 163:419-436.

14. Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011; 72(2):231-43.

15. Halassa MM, Acsády L. Thalamic Inhibition: Diverse Sources, Diverse Scales. Trends Neurosci. 2016; 39(10):680-693.

16. Wang X, Leong ATL, Chan RW, et al. Thalamic low frequency activity facilitates resting-state cortical interhemispheric MRI functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2019 ;201:115985.

17. Chan RW, Leong ATL, Ho LC, et al. Low-frequency hippocampal-cortical activity drives brain-wide resting-state functional MRI connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 ;114(33):E6972-E6981.

18. Grandjean J, Buehlmann D, Buerge M, et al. Psilocybin exerts distinct effects on resting state networks associated with serotonin and dopamine in mice. Neuroimage. 2021;225:117456.

19. Lu H, Jaime S, Yang Y. Origins of the Resting-State Functional MRI Signal: Potential Limitations of the "Neurocentric" Model. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1136.

Figures