4003

Optimization of spin-lock preparation pulses for B1 and B0 insensitive cardiac T1ρ mapping1School of Biomedical Engineering, ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai, China, 2Shanghai Clinical Research and Trial Center, Shanghai, China, 3UIH America, Inc., Houston, TX, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Myocardium, Tissue Characterization

Cardiac T1ρ mapping is a promising technique for assessment of myocardial fibrosis without exogenous contrast agent. However, its wide application is hindered by the sensitivity of T1ρ preparation to B1 and B0 inhomogeneities. In this study, the state-of-the-art constant spin-lock methods including the composite and adiabatic excitation continuous-wave spin-lock methods were investigated using numerical simulations to assess their robustness to field inhomogeneities, and validated in phantoms and a preliminary subject. Two T1ρ preparation modules were found to generate superior T1ρ mapping quality in the presences of B0 and B1 inhomogeneities, indicating the potential of clinical application of cardiac T1ρ MRI.Introduction

Cardiac T1ρ mapping is an emerging technique for assessment of focal and diffuse myocardial fibrosis without exogenous contrast agent 1-5. However, T1ρ CMR is challenging due to the sensitivity of T1ρ preparation (T1ρ prep) to B1 RF and B0 inhomogeneities. Various spin-lock techniques have been proposed to mitigate the influence of B1 and/or B0 field inhomogeneities, including the composite spin-lock (CSL) pulses 6,7 and the adiabatically excited continuous-wave spin-lock (ACW-SL) method 8. Especially, the ACW-SL has recently shown promising results for cardiac T1ρ mapping at 3T 9, while the key component, adiabatic excitation pulse, has not been systematically optimized. In this study, we optimized the pulse parameters for two commonly used adiabatic excitation pulses using numerical simulations and compared the optimized ACW-SL with the state-of-the-art composite spin-lock methods in phantoms and in vivo cardiac T1ρ mapping.Methods

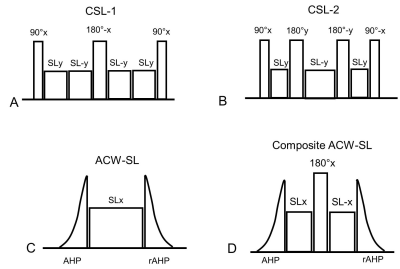

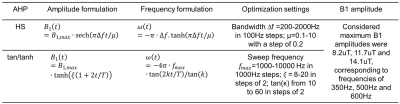

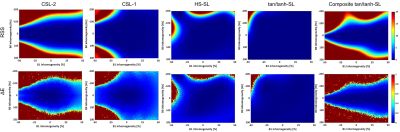

Four T1ρ prep modules were considered (Fig. 1): the composite spin-lock methods 7 with one (CSL-1) or two (CSL-2) 180° refocusing pulses for simultaneous B1 and B0 inhomogeneity compensation; the ACW-SL which consists of the adiabatic half-passage (AHP) tip-down pulse, the spin-lock pulse and the reverse AHP tip-up pulse (rAHP); the composite ACW-SL which has an additional refocusing pulse. The hyperbolic secant (HS) and tangent/hyperbolic tangent (tan/tanh) pulses were considered for the AHP. The amplitude and phase formulations of the two pulses are provided in Table 1. The pulse parameters were optimized in the following Bloch simulations.Numerical simulations: Bloch simulations were performed for B0 inhomogeneity ranging from -200Hz to 200Hz and for B1 inhomogeneity ranging from -50% to 50% 10. For each combination of B0 and B1 inhomogeneities, the longitudinal magnetizations (Mz) were calculated for a range of spin-lock durations (TSL) from 0 to T1ρ. The spin-lock frequency was set to 350Hz 9. The myocardial T1ρ was to 50ms, while T2ρ was assumed to be 75ms 11. The residual sum of squares (RSS) between Mz and the mono-exponentially decayed signal Mz,d was calculated to assess the banding susceptibility: $$$RSS=\sum_n(M_{z,d}(n)-M_{z}(n))^{2}$$$. For quantification error (ΔE) analysis, the simulated longitudinal magnetizations were divided into four equally spaced segments and one sample was randomly selected in each segment for T1ρ fitting. The random T1ρ fitting process was repeated for 100 times to calculate the mean quantification error.

Optimization of the AHP pulse: The AHP pulse duration was set to 4ms for a tradeoff between satisfying the adiabatic condition and reducing relaxation during the AHP. Table 1 summarizes the optimization settings for the HS and tan/tanh pulses. For each pulse design considered, the RSS was calculated for 30 frequencies across ±150 Hz and 20 B1 field amplitudes between 70% and 130% of the maximum constraint. The brute-force search selected the set of design parameters that had the lowest RSS.

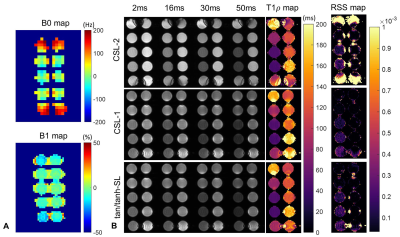

Imaging Experiments: The T1ρ prep methods of CSL-1, CSL-2 and ACW-SL with the optimized AHP pulse were implemented in a 3T United Imaging MR system, and compared in phantoms made of agarose and gadolinium contrast and in one healthy volunteer. The 2D T1ρ prep bSSFP 9 was performed with spin-lock frequency of 350Hz and TSL of 2, 16, 30 and 50ms under a single breath-hold of 10 heartbeats (two dummy cardiac cycles between TSL acquisitions). Volume shimming mode was adopted.

Results

Seeing from the RSS and ΔE maps in Fig. 2, the CSL-1 and ACW-SL with the optimized tan/tanh pulse are the two most robust methods, immune to a wide range of field inhomogeneities. The introduction of additional refocusing pulse to the ACW-SL degraded its performance. Figure 3 and 4 respectively shows the phantom and in vivo T1ρ mapping results and the B1 and B0 field maps. There are severe B0 inhomogeneities in the top and bottom phantoms, while the CSL-1 and tan/tanh-SL provided more reliable T1ρ-weighted images than the CSL-2, as evident by the T1ρ and RSS maps.Discussion

The state-of-the-art constant spin-lock methods were investigated using numerical simulations, and validated in phantoms and a preliminary subject. The CSL-1 and optimized tan/tanh-SL methods are able to generate superior T1ρ mapping quality in the presences of B0 and B1 inhomogeneities. The optimized B1 amplitude for the tan/tanh pulse is the same to the spin-lock pulse, which echoes the previous finding 8 that the ACW-SL is robust to both B1 and B0 inhomogeneities when the B1 amplitude of the AHP and the rAHP pulse is the same to that of the spin-lock pulse.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Bustin A, Toupin S, Sridi S, Yerly J, Bernus O, Labrousse L, Quesson B, Rogier J, Haissaguerre M, van Heeswijk R, Jais P, Cochet H, Stuber M. Endogenous assessment of myocardial injury with single-shot model-based non-rigid motion-corrected T1 rho mapping. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2021;23(1):119.

2. Han Y, Liimatainen T, Gorman RC, Witschey WR. Assessing Myocardial Disease Using T1rho MRI. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 2014;7(2):9248.

3. Qi H, Bustin A, Kuestner T, Hajhosseiny R, Cruz G, Kunze K, Neji R, Botnar RM, Prieto C. Respiratory motion-compensated high-resolution 3D whole-heart T1rho mapping. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2020;22(1):12.

4. Thompson EW, Kamesh Iyer S, Solomon MP, Li Z, Zhang Q, Piechnik S, Werys K, Swago S, Moon BF, Rodgers ZB, Hall A, Kumar R, Reza N, Kim J, Jamil A, Desjardins B, Litt H, Owens A, Witschey WRT, Han Y. Endogenous T1rho cardiovascular magnetic resonance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2021;23(1):120.

5. Witschey WR, Zsido GA, Koomalsingh K, Kondo N, Minakawa M, Shuto T, McGarvey JR, Levack MM, Contijoch F, Pilla JJ, Gorman JH, 3rd, Gorman RC. In vivo chronic myocardial infarction characterization by spin locked cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14:37.

6. Gram M, Seethaler M, Gensler D, Oberberger J, Jakob PM, Nordbeck P. Balanced spin-lock preparation for B1 -insensitive and B0 -insensitive quantification of the rotating frame relaxation time T1rho. Magn Reson Med 2021;85(5):2771-2780.

7. Witschey WRT, Borthakur A, Elliott MA, Mellon E, Niyogi S, Wallman DJ, Wang CY, Reddy R. Artifacts in T1p-weighted imaging: Compensation for B-1 and B-0 field imperfections. J Magn Reson 2007;186(1):75-85.

8. Chen W. Artifacts correction for T1rho imaging with constant amplitude spin-lock. J Magn Reson 2017;274:13-23.

9. Qi H, Lv Z, Hu J, Xu J, Botnar R, Prieto C, Hu P. Accelerated 3D free-breathing high-resolution myocardial T1rho mapping at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med 2022;88(6):2520-2531.

10. Kellman P, Herzka DA, Hansen MS. Adiabatic Inversion Pulses for Myocardial T1 Mapping. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2014;71(4):1428-1434.

11. Wheaton AJ, Borthakur A, Kneeland JB, Regatte RR, Akella SV, Reddy R. In vivo quantification of T1rho using a multislice spin-lock pulse sequence. Magn Reson Med 2004;52(6):1453-1458.

Figures