3936

Simultaneous in vivo Detection of Cystathionine and 2HG at 7T and Simulation of MEGA and SLOW-editing performance1Support Center for Advanced Neuroimaging (SCAN), University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 2Translational Imaging Center, sitem-insel, Bern, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Pulse Sequence Design, Spectroscopy, Spectral editing

2-Hydroxyglutarate (2HG) is a biomarker for IDH-mutant glioma, and previous studies have shown that cystathionine (Cys) can be a potential biomarker for 1q/19q co-deletion of glioma. Previous studies used SVS based MEGA-editing MRS to detect 2HG and co-edited Cys, but editing efficiency of Cys is not optimal due to the narrow bandwidth of the applied MEGA editing-pulses. This work shows that SLOW-editing is able to detect both 2HG and Cys in an optimal way with whole-brain coverage.

INTRODUCTION

Two important factors that determine the prognosis of glioma patients are (i.) the isocitrate-dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status [1] and (ii.) codeletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q (1p/19q codeletion) [1]. In IDH-mutated glioma patients, accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG) can be detected [2], [3], whereas in 1p/19q co-deleted glioma a potential accumulation of cystathionine (Cys) can be detected using SVS MR-spectroscopy [4]–[6]. However, the editing efficiency for Cys was not optimal in previous studies if the center frequency of the MEGA pulses was set to 1.9 ppm [5]. This is because the target hitting J-coupled spin of Cys is at 2.16 ppm, and the passband of MEGA pulses is too narrow to cover both 1.9 and 2.16 ppm. In this study performed at 7T, we investigated whether it is possible to simultaneously and optimally detect both 2HG as well as Cys. We choose SLOW-editing based EPSI sequence (SLOW-EPSI) which was originally designed and used in the past for detection of 2HG only [7]. However, this study shows that SLOW-editing is able to detect both 2HG and Cys in an optimal way. In contrast to SVS or 2D-MRSI techniques where the VOI must be selected at measurement time, SLOW-EPSI sequence allows flexible analysis of multiple tumor subregions at analysis time, further enlarging the diagnostic precision of MRSI.METHODS

Simulations — Simulation of SLOW- and MEGA- editing performance at 7T was performed using an in-house developed program using MATLAB (R2019b). The program solves the relaxation-free Liouville-von Neumann Equation [8]. The MEGA-pulses were Sinc Gaussian shaped with 8.3 ms duration and 128 Hz full width at half maximum (HWHM) [9]. The center frequency of MEGA-on pulses was set at 1.9 ppm. The SLOW-pulse were listed below.Measurements — The MRSI was performed on a Siemens 7T scanner (MAGNETOM Terra, Germany) using the Nova 1Tx 32Rx head coil. One patient with glioma suspected glioma has been prospectively examined, and followed by surgery and neuropathology to determine the IDH-status and 1p/19q status.

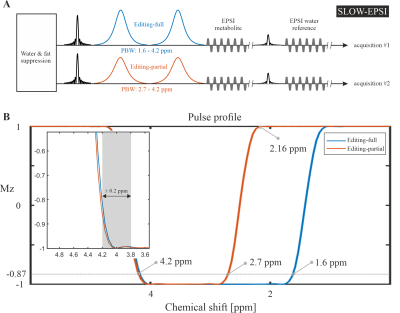

The SLOW-EPSI sequence [7], [10] (Figure 1) was applied on a glioma patient with following parameters:

TE = 68 ms, TR = 1500 ms, matrix = 65 × 23 × 9 (4.3 × 7.8 × 7.8 mm), FOV = 280 × 180 × 70 mm, averages = 1, and TA = 9 min. The refocusing/editing chemical-selective adiabatic pulse (CSAP) for SLOW-editing is 24 ms duration. The bandwidth (full width at 87% maximum) of editing-full and editing-partial ranges from 1.6 – 4.2 ppm and 2.7 – 4.2 ppm, respectively (Figure 1B). The editing result was obtained by the subtraction of editing-full (acquisition #1) and editing-partial (acquisition #2). In SLOW-editing, the 2π- CSAP acts at the same time as both refocusing and editing pulse.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

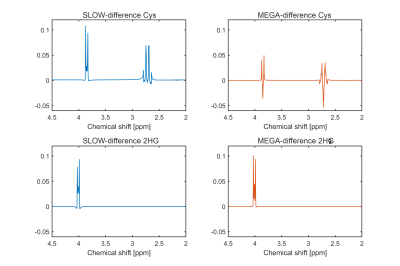

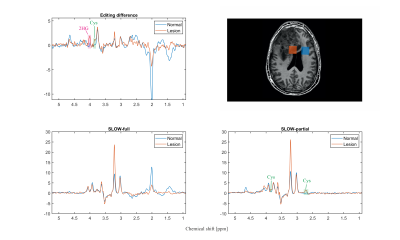

Simulation results — The simulation (Figure 2) shows SLOW and MEGA have a similar editing pattern for 2HG at 4.01 ppm, but quite different patterns for Cys at 3.85 and 2.72 ppm. The significant difference for Cys is due to the center frequency of MEGA-pulses being 0.26 ppm (2.16-1.9) away from the target J-coupled spin at 2.16 ppm, resulting in a reduction in editing efficiency [5].Patient measurement — The Cys and 2HG were both detected in the patient with SLOW-EPSI, as shown in Figure 3. The editing peak of Cys at 3.85 ppm appears as a “shoulder” in the editing difference spectrum. In contract, the editing peak of Cys at 2.72 ppm is not seen in the editing difference spectrum, but clearly present in the SLOW-partial spectrum. This could be mainly due to the lipid contamination affecting the baseline of the SLOW-full spectrum from 1.3-2.8 ppm, resulting in a fluctuation of the baseline in the editing difference spectrum. However, the baseline of the SLOW-partial spectrum is much less affected by lipids. Therefore the peak of Cys at 2.72 ppm is present in the SLOW-partial spectrum.

Discussion — The simulation result shows that SLOW-editing is relatively robust to B1+/B0-inhomogeneities compared to MEGA-editing (Figure 4). The editing peak for Cys at 3.85 ppm is robust and has the optimal editing efficiency in the range of [-0.4 ppm, 0.3 ppm] and [40%, 220%], and the peak at 2.72 ppm is robust and has the optimal editing efficiency in the range of [-0.1 ppm, 0.3 ppm] and [40%, 220%]. In contrast, MEGA-editing is highly sensitive to B1+/B0-inhomogeneities, and its optimal editing efficiency is obtained at a shift of ~0.26 ppm.

CONCLUSION

This work shows that SLOW can be used for the simultaneous in vivo detection of both Cys and 2HG in glioma patients and maintains optimal editing efficiency for both Cys and 2HG. In contrast to MEGA, one must select one of the two metabolites to be optimally edited. Furthermore, SLOW-editing performance (i.e. efficiency) is significantly more insensitive to B1+/B0-inhomogeneities occurring in vivo as compared to MEGA-editing efficiency.Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF-182569).References

[1] D. N. Louis et al., “The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary,” Neuro Oncol, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 1231–1251, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab106.

[2] O. C. Andronesi et al., “Detection of 2-Hydroxyglutarate in IDH-Mutated Glioma Patients by In Vivo Spectral-Editing and 2D Correlation Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 4, no. 116, pp. 116ra4-116ra4, Jan. 2012, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002693.

[3] C. Choi et al., “2-Hydroxyglutarate detection by magnetic resonance spectroscopy in IDH-mutated patients with gliomas,” Nat Med, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 624–629, Apr. 2012, doi: 10.1038/nm.2682.

[4] F. Branzoli et al., “Cystathionine as a marker for 1p/19q codeleted gliomas by in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy,” Neuro Oncol, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 765–774, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.1093/NEUONC/NOZ031.

[5] F. Branzoli, D. K. Deelchand, M. Sanson, S. Lehéricy, and M. Marjańska, “In vivo 1 H MRS detection of cystathionine in human brain tumors,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 82, no. 4, pp. 1259–1265, Oct. 2019, doi: 10.1002/mrm.27810.

[6] F. Branzoli et al., “The influence of cystathionine on neurochemical quantification in brain tumor in vivo MR spectroscopy,” Magn Reson Med, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1002/MRM.29252.

[7] G. Weng et al., “SLOW: A novel spectral editing method for whole‐brain MRSI at ultra high magnetic field,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 88, no. 1, pp. 53–70, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1002/mrm.29220.

[8] J. Slotboom, A. F. Mehlkopf, and W. M. M. J. Bovee, “The Effects of Frequency-Selective RF Pulses on J-Coupled Spin-1/2 Systems,” J Magn Reson A, vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 38–50, May 1994, doi: 10.1006/JMRA.1994.1086.

[9] C. Chen et al., “Activation induced changes in GABA: Functional MRS at 7 T with MEGA-sLASER,” Neuroimage, vol. 156, pp. 207–213, Aug. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.05.044.

[10] A. Ebel and A. A. Maudsley, “Improved spectral quality for 3D MR spectroscopic imaging using a high spatial resolution acquisition strategy,” Magn Reson Imaging, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 113–120, 2003, doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(02)00645-8.

[11] J. Slotboom et al., “Proton Resonance Spectroscopy Study of the Effects of L-Ornithine-L-Aspartate on the Development of Encephalopathy, Using Localization Pulses with Reduced Specific Absorption Rate,” J Magn Reson B, vol. 105, no. 2, Oct. 1994, doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1114.

Figures