3935

Zero filling does not inherently improve precision of real relative to complex-domain fitting in 1H-MR spectra with physiological baselines1Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 2Radiology, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, Spectroscopy

There remains controversy surrounding the use of zero filling during spectral quantification of in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectra (1H-MRS) using linear combination model (LCM) fitting. We examine the potential mixing of real and imaginary information theorized with zero filling, and whether this is demonstrated by a comparable change in accuracy and precision provided by complex fitting. We show that application of zero filling does improve fitting precision when a baseline is not present; with an imperfectly modeled unknown in vivo baseline, however, zero filling does not necessarily reduce error in real relative to complex fits.Purpose

Spectral quantification of 1H-MR spectra commonly involves linear combination modeling (LCM) of the real spectrum1-6. Previously, we demonstrated that the application of complex fitting, in which both the real and imaginary spectra are fit in parallel, consistently improves metabolite quantification precision and even accuracy7.Some may argue, however, whether the application of zero filling can recuperate the differences in accuracy and precision provided by complex fitting. It is theorized that with the application of zero filling, the real and imaginary information become Hilbert pairs, allowing for full complex information in the real spectrum alone8. However, contradictory information is present regarding whether to apply zero filling during quantification1,9,10.

Here we systematically examine differences in spectral quantification errors between real and complex fitting across zero-filling conditions. This allows us to determine whether information exchange occurs when zero filling the real spectrum, and whether that is comparable to the accuracy and precision provided by complex fitting.

Methods

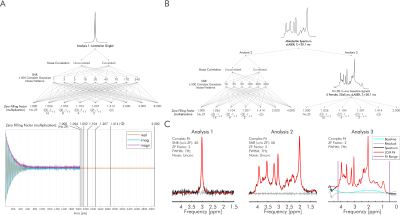

Previously simulated Lorentzian singlets, metabolite spectra, and metabolite spectra with in vivo baselines,7 were further processed to systematically compare LCM real and complex fitting with varying levels of applied zero filling. This was conducted using INSPECTOR11 with batch functionality12,13. For all analyses, the corresponding simulated noiseless basis set used for simulating the spectra was also used for fitting.All 9000 (500 spectra x 9 SNRs x 2 previously defined noise correlations7) previously simulated Lorentzian singlets were analyzed for each of 9 zero-filling conditions (Figure 1A). Fit optimization solely consisted of amplitude scaling (Figure 1C).

Similarly, all 6000 (500 spectra x 6 SNRs x 2 noise correlations) previously simulated in vivo-like metabolite spectra (MARSS14, 3 T, sLASER15, TE = 20.1 ms, 2048 complex points, 19 metabolites with physiologic T2 and concentration7), were analyzed at 7 zero-filling conditions (Figure 1B). Fit optimization included metabolite-specific amplitude scaling, Lorentzian broadening and frequency shift, as well as global zero-order phase and baseline offset (Figure 1C).

Finally, all previously developed spectra with baselines, consisting of noiseless simulated metabolite spectra combined with measured prefrontal and occipital cortex macromolecule baselines (20 total)16 using previously described methods13,17, were analyzed at 6 zero-filling conditions (Figure 1B). As before7, the basis spectra and fit optimization employed additional Gaussian shapes in the basis set and a cubic spline baseline (1-ppm knot interval, no smoothing) to account for macromolecules and baseline shape respectively (Figure 1C).

Percent error for metabolite estimations was determined relative to perfect (no residual), noiseless, no-baseline fits. Statistical tests (R version 4.1.218) involved ANOVAs, post-hoc Tukey's test, and F-tests for the equality of variances for analysis of average and standard deviation of percent error. All post-hoc comparisons were corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg method for the total number of pairs within that analysis’ zero-filling condition.

Results

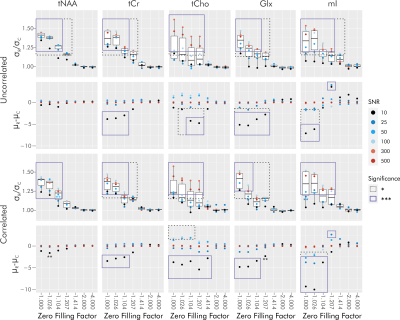

For singlets without zero filling, real fitting has a consistently higher standard deviation of percent error by a factor of approximately √2 (Figure 2A). As zero filling increases, the ratio of real to complex fit error standard deviation approaches unity, with a plateau at a zero-filling factor of √2 and a lack of statistical significance following a zero-filling factor of 1.026 (Figure 2A). No significant differences in average percent error were observed. Changes in complex fit results with zero filling were not observed (Figure 2B).For metabolite spectra without a baseline and without zero filling, complex fitting provides a consistently lower error standard deviation, with SNR- and metabolite-dependent variations in the degree of improvement (Figure 3). With increasing zero filling, the ratio of standard deviation approaches unity, with a plateau at a zero-filling factor of 2 and a lack of statistical significance with zero filling exceeding a factor of √2. Without zero filling, complex fitting provides an average percent error closer to zero for all but 1 (total-choline, tCho, at SNR 10) statistical difference. Statistical differences in average are no longer apparent with zero filling exceeding a factor of √2.

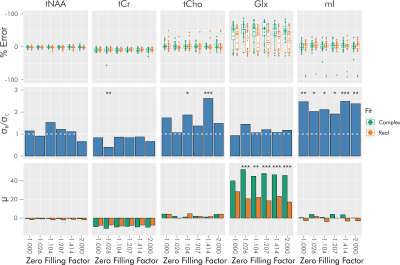

When considering baselines, differences between real and complex fitting vary heavily by metabolite, with maximal effects in myoinositol (mIns) (whose error standard deviation favors complex fitting) and glutamate plus glutamine (Glx) (whose error average favors real fitting) (Figure 4). This remains consistent across zero-filling conditions. For tCho and mIns, real fitting consistently provides more extreme estimates across zero-filling conditions.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that without zero filling, complex relative to real fitting consistently provides lower standard deviation and average percent error, improving precision and accuracy in a metabolite- and SNR-dependent manner.As zero filling is applied, the differences in precision and accuracy between real and complex fitting are attenuated, with a consistent plateau achieved around a zero-filling factor of √2. However, when considering spectra with in vivo baselines, zero filling does not inevitably reduce differences observed between real and complex fitting.

Altogether, although zero filling may theoretically recuperate improvements in accuracy and precision provided by complex fitting without zero filling, the presence of physiological baselines may provide confounding factors in the fit that make the application of zero filling largely ineffective. In addition, zero filling has been previously shown to complicate the calculation of Cramér-Rao Lower Bounds19. Further investigation is needed for generalization of these effects, including examination of additional baselines and baseline modeling methods.

Acknowledgements

This work was performed at the Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute MRI Platform, a shared resource. In vivo measurements were derived from research conducted in accordance with Columbia University Institutional Review Board protocol AAAQ9641.References

1. Near J, Harris AD, Juchem C, Kreis R, Marjańska M, Öz G, Slotboom J, Wilson M, and Gasparovic C. Preprocessing, analysis and quantification in single-voxel magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Experts' consensus recommendations. NMR in Biomedicine 34 (5) (2021).

2. Mierisova S and Ala-Korpela M. MR spectroscopy quantitation: A review of frequency domain methods. NMR in Biomedicine 14:247–259 (2001).

3. Zöllner HJ, Povazan M, Hui SCN, Tapper S, Edden RAE, and Oeltzschner G. Comparison of different linear-combination modeling algorithms for short-TE proton spectra. NMR in Biomedicine 34(4) (2021).

4. Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 30:672-679 (1993).

5. Provencher SW. LCModel & LCMgui User’s Manual 2021.

6. Swanberg KM, Landheer K, Pitt D, and Juchem C. Quantifying the metabolic signature of multiple sclerosis by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Current challenges and future outlook in the translation from proton signal to diagnostic biomarker. Frontiers in Neurology 10 (1173) (2019).

7. Campos LC, Swanberg KM, Gajdošík M, Landheer K, and Juchem C. Complex fitting of 1H-MR spectra improves quantification precision independent of SNR and noise correlation. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 0430 (2022).

8. R. R. Ernst and E. Bartholdi. Fourier Spectroscopy and the Causality Principle," Journal of Magnetic Resonance 11: 9-19 (1973).

9. Landheer K and Juchem C. The effects of cutting/zero-filling and linebroadening on quantification of magnetic resonance spectra via maximum-likelihood estimation. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 2834 (2021).

10. Manohar SM, Oeltzschner G, Barker PB, and Edden RAE. The value of zero filling in in vivo MRS. bioRxiv 93:1-2 (2022).

11. Gajdošík M, Landheer K, Swanberg KM, and Juchem C. INSPECTOR: Free software for magnetic resonance spectroscopy data Inspection, processing, simulation and analysis. Scientific Reports 11, 2094 (2021).

12. Swanberg KM, Prinsen H, and Juchem C. Spectral quality differentially affects apparent concentrations of individual metabolites as estimated by linear combination modeling of in vivo MR spectroscopy data at 7 Tesla. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 4327 (2019).

13. Swanberg KM, Landheer K, Gajdošík M, Treacy MS, and Juchem C. Hunting the perfect spline: Baseline handling for accurate macromolecule estimation and metabolite quantification by in vivo 1H MRS. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 2856 (2020).

14. Landheer K, Swanberg KM, and Juchem C. Magnetic resonance Spectrum simulator (MARSS), a novel software package for fast and computationally efficient basis set simulation. NMR in Biomedicine 34 (2021).

15. Landheer K, Gajdosik M, and Juchem C. A semi-LASER, single-voxel spectroscopic sequence with a minimal echo time of 20.1 ms in the human brain at 3 T. NMR in Biomedicine 33 (2020).

16. Landheer K, Gajdošík M, Treacy M, Juchem C. Concentration and effective T2 relaxation times of macromolecules at 3T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 84(5):2327-2337 (2020).

17. Swanberg KM, Gajdošík M, Landheer K, and Juchem C. Computation of Cramér-Rao Lower Bounds (CRLB) for spectral baseline shapes. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 2010 (2021).

18. R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/. version 4.1.2.

19. Landheer K, Juchem C. Are Cramer-Rao lower bounds an accurate estimate for standard deviations in in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy? NMR in Biomedicine (34) (2021).

Figures