3926

Improved glutamine detection using diffusion-weighted SPECIAL at 14.1T1LIFMET, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2CIBM Center for Biomedical Imaging, Lausanne, Switzerland, 3Animal Imaging and Technology (AIT), EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Spectroscopy, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, brain, preclinical, sequence design

Brain glutamine (Gln) is a key biomarker of hepatic encephalopathy (HE). The estimation of its diffusion properties with diffusion-weighted MRS is of high interest in the field but remains challenging due to its low concentration. We propose a new diffusion-weighted MRS sequence, DW-SPECIAL, which enables to reach shorter echo times and is thus beneficial for strongly J-coupled metabolites such as Gln. DW-SPECIAL reduces the uncertainty in Gln diffusion decays and the standard deviation across animals for Gln diffusivity in a homogenous control population and paves the way for an in-depth study of Gln diffusion properties in HE.

Introduction

Among the MR spectroscopy-observable brain metabolites, glutamine (Gln) correlates most reliably with the severity of hepatic encephalopathy (HE)1. When diffusion-sensitizing gradients are added to single-voxel MR spectroscopy (MRS) sequences, cell-specific microstructure can be inferred by assessing the diffusion proprieties of the major brain metabolites2–5, complementary to the metabolic information. In the context of type C HE, diffusion-weighted MRS (DW-MRS) successfully probed changes in metabolite diffusivities, including in Gln, in the cerebellum of a rat model of the disease, both in adult6 and young rats7, confirming the loss of neuronal and astrocytic structure observed by histology. In this rat model, the excess of ammonia causes a brain Gln increase of more than 100%8, thus facilitating its quantification. However, reliable estimation of Gln diffusion properties in the control group, where its concentration is low, remains challenging. To tackle this issue, we propose a new diffusion-weighted MR spectroscopy sequence, the DW-SPECIAL sequence, based on the semi-adiabatic SPECIAL sequence9,10 already used for single-voxel spectroscopy. Overall, due to its shorter echo time (TE), DW-SPECIAL improves the quantification of strongly J-coupled metabolites. In particular, we show its superiority over STE-LASER11, the current gold standard preclinical DW-MRS sequence, for Gln diffusion decay estimation in the control group of HE rats.Methods

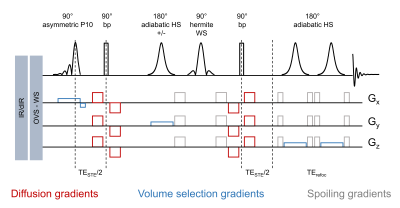

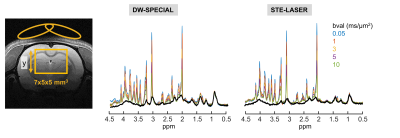

The sequence diagram and the pulse details are presented in Fig 1. DW-SPECIAL combines a stimulated echo (STE) diffusion block with a semi-adiabatic SPECIAL localisation. The on/off ISIS scheme performs a slice-selective adiabatic inversion (HS, 2 ms, 10 kHz) on the inhomogeneous direction (y), here perpendicular to the T/R quadrature surface coil, and requires a two-step phase cycling. Diffusion gradients are inserted in the STE block in a bipolar fashion.Diffusion-weighted MRS acquisitions on a Bruker 14.1T scanner were performed on N=3 SHAM-operated and N=3 bile-duct ligated (BDL) adult male Wistar rats, a model of type C hepatic encephalopathy, with the DW-SPECIAL and the STE-LASER, the latter being used as a reference. The shortest achievable total TE was used for each sequence: 18.5 ms for DW-SPECIAL and 33 ms for STE-LASER, with the following parameters: TR/Δ/δ=3000/43/3 ms, where Δ is the diffusion time and δ the duration of each diffusion gradient, set in the direction (1,1,1). 5 b-values between 0.05 to 10 ms/µm2 were acquired in a 175 µL voxel (Fig 2). Eddy currents correction using the water reference scan was applied, followed by B0 drift and phase corrections on individual shots. A metabolite basis-set was simulated with NMRScope-B12 (jMRUI) and a macromolecule (MM) spectrum was acquired in vivo with each sequence using double inversion recovery (TI=2200/800 ms) with b=5 ms/µm2 where residual metabolites were removed using AMARES (jMRUI)13,14. Concentrations were quantified with LCModel15 and the Callaghan’s randomly oriented sticks model16 was fitted to the individual animal metabolite decays.

Results and discussion

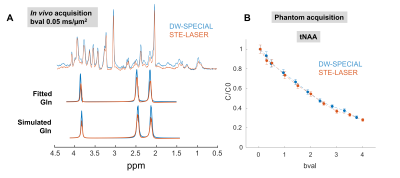

The newly proposed DW-SPECIAL sequence allows to halve the minimum echo time as compared to the one in STE-LASER (18 ms versus 33 ms), while preserving the advantages of the latter (Fig 1): the possibility to reach long diffusion times, a sharp volume selection thanks to asymmetric and adiabatic pulses, and a limited sensitivity to B1 inhomogeneities. Similarly to STE-LASER, no cross-terms between the diffusion and imaging/spoiling gradients contributed to the b-value in DW-SPECIAL, as long as the slice-refocusing gradient of the first 90° pulse and the first diffusion gradient are not applied simultaneously. This was confirmed experimentally in a phantom, where an identical total N-acetylaspartate (tNAA) free diffusion decay was observed for both sequences (Fig 3B).Good quality spectra were obtained with both sequences at all b-values (Fig 2). The MM background contribution was higher in DW-SPECIAL due to the shorter TE. For Gln which is strongly J-coupled, the shorter TE achieved in DW-SPECIAL yielded less signal loss by J-evolution, as predicted by simulations (Fig 3A).

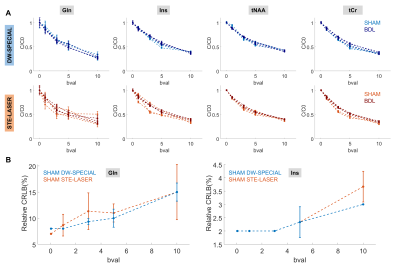

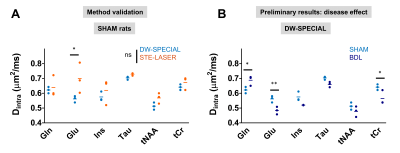

DW-SPECIAL reduced the standard deviation between diffusion decays (Fig 4A) and between estimated Dintra for J-coupled metabolites like Gln and myo-inositol (Ins) in the control group (Fig 5A), expected to be a homogeneous population. The relative Cramer Rao Lower Bounds (CRLB) are also reduced for Gln and Ins with DW-SPECIAL, irrespective of the b-value (Fig 4B). For future studies, such data quality may facilitate the quantification of the diffusion decays of the low-concentrated metabolites and/or the access to higher b-values.

Glutamate (Glu) Dintra showed a statistically significant difference between the two sequences (Fig 5A), which could originate from a biased quantification of low-concentrated Gln in STE-LASER together with the difficulty to separate Gln from Glu diffusion properties.

To additionally validate the performance of DW-SPECIAL in pathology, we assessed the preliminary differences between the BDL and the control group (Fig 5B). BDL rats show a higher Gln Dintra compared to the control group, echoing our previous DW-MRS results in the cerebellum, and lower Glu and tCr Dintra. Possible brain-regional differences should be further investigated by increasing the sample size.

Conclusion

We show a first implementation of the DW-SPECIAL sequence improving the quantification and subsequent diffusivity measurements of J-coupled metabolites, such as Gln and Ins. As a direct application, this new sequence paves the way for a better estimation of Gln diffusion properties in the control group of hepatic encephalopathy studies.Acknowledgements

Supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 813120 (INSPiRE-MED), the SNSF projects no 310030_173222, 310030_201218 and the Leenaards and Jeantet Foundations. We acknowledge access to the facilities and expertise of the CIBM Center for Biomedical Imaging, founded and supported by Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), University of Lausanne (UNIL), Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), University of Geneva (UNIGE) and Geneva University Hospitals (HUG). We acknowledge Stefanita Mitrea and Dario Sessa for the BDL surgeries, Analina Da Silva and Mario Lepore for veterinary support, Thanh Phong Lê for technical support and Vladimir Mlynarik for experimental advice.

References

1. Zeng, G. et al. Meta-analysis of magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurology 94, e1147–e1156 (2020).

2. Ronen, I., Ercan, E. & Webb, A. Axonal and glial microstructural information obtained with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 7T. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 7, 13 (2013).

3. Palombo, M., Ligneul, C., Hernandez-Garzon, E. & Valette, J. Can we detect the effect of spines and leaflets on the diffusion of brain intracellular metabolites? NeuroImage 182, 283–293 (2018).

4. Valette, J., Ligneul, C., Marchadour, C., Najac, C. & Palombo, M. Brain Metabolite Diffusion from Ultra-Short to Ultra-Long Time Scales: What Do We Learn, Where Should We Go? Front Neurosci 12, 2 (2018).

5. Najac, C., Branzoli, F., Ronen, I. & Valette, J. Brain intracellular metabolites are freely diffusing along cell fibers in grey and white matter, as measured by diffusion-weighted MR spectroscopy in the human brain at 7 T. Brain Struct Funct 221, 1245–1254 (2016).

6. Mosso, J. et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the cerebellum of a rat model of hepatic encephalopathy at 14.1T. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 29 (2021).

7. Mosso, J. et al. Diffusion MRI and MRS probe cerebellar microstructure alterations in the rat developing brain during hepatic encephalopathy. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30 (2022).

8. Braissant, O. et al. Longitudinal neurometabolic changes in the hippocampus of a rat model of chronic hepatic encephalopathy. J. Hepatol. 71, 505–515 (2019).

9. Mlynárik, V., Gambarota, G., Frenkel, H. & Gruetter, R. Localized short-echo-time proton MR spectroscopy with full signal-intensity acquisition. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 56, 965–970 (2006).

10. Xin, L., Schaller, B., Mlynarik, V., Lu, H. & Gruetter, R. Proton T1 relaxation times of metabolites in human occipital white and gray matter at 7 T. Magn Reson Med 69, 931–936 (2013).

11. Ligneul, C., Palombo, M. & Valette, J. Metabolite diffusion up to very high b in the mouse brain in vivo: Revisiting the potential correlation between relaxation and diffusion properties. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 77, 1390–1398 (2017).

12. Starčuk, Z. & Starčuková, J. Quantum-mechanical simulations for in vivo MR spectroscopy: Principles and possibilities demonstrated with the program NMRScopeB. Anal Biochem 529, 79–97 (2017).

13. Kunz, N. et al. Diffusion-weighted spectroscopy: a novel approach to determine macromolecule resonances in short-echo time 1H-MRS. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 64, 939–946 (2010).

14. Simicic, D. et al. In vivo macromolecule signals in rat brain 1H-MR spectra at 9.4T: Parametrization, spline baseline estimation, and T2 relaxation times. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 86, 2384–2401 (2021).

15. Provencher, S. W. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med 30, 672–679 (1993).

16. Callaghan, P. T., Jolley, K. W. & Lelievre, J. Diffusion of water in the endosperm tissue of wheat grains as studied by pulsed field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance. Biophys J 28, 133–141 (1979).

17. Tkác, I., Starcuk, Z., Choi, I. Y. & Gruetter, R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of rat brain at 1 ms echo time. Magn Reson Med 41, 649–656 (1999).

Figures

Fig 1. DW-SPECIAL sequence diagram. First 90° pulse: slice-selective asymmetric P10 (0.5 ms, 13.5 kHz, 18% refocusing factor), allowing to reduce the minimum TE. 2nd and 3rd 90° pulses: non slice-selective square (0.1 ms, 12.8 kHz). Bipolar diffusion gradients limit the effects of Eddy-Currents. The adiabatic inversion is performed on the y direction with strong B1 inhomogeneities. Water suppression: VAPOR17. No cross-terms between diffusion and imaging gradients contribute to the b-value. Spoiler gradients were adjusted empirically (arbitrary values displayed).

Fig 2. Voxel location and representative diffusion sets for the two sequences. 160 shots were acquired for b up to 5 ms/µm2 and 320 for b=10 ms/µm2. The water linewidth was ranging from 17 to 20 Hz and an additional 2 Hz line broadening was applied for display. The macromolecule spectrum (black) acquired with double-inversion recovery and additional diffusion-weighting (b=5 ms/µm2) with each sequence is overlapped.

Fig 3. Validation of the DW-SPECIAL sequence. A, top: overlapped spectra at b=0.05 ms/µm2. The difference for singlets is linked to slightly different voxel selections and underlying MM, the effect of T2 relaxation being minimal between 18 ms and 33 ms. A, bottom: Gln fit extracted from LCModel quantification and predicted patterns from the basis-set simulations, confirming a greater loss by J-evolution in STE-LASER. B: Diffusion decay of total N-acetylaspartate (tNAA) in a phantom, where the closely-matching diffusion decays confirm the absence of cross-terms in DW-SPECIAL.

Fig 5. Estimated Dintra with Callaghan’s model. A: Dintra estimation from the two sequences for SHAM rats and for a few metabolites of interest. No overall significant difference was observed between the sequences, except for Glu. B: Group comparison with DW-SPECIAL of Dintra in this brain region and disease effect. Despite the small sample size, BDL rats tentatively show higher Dintra for Gln and lower for Glu and tCr compared to the control group. Statistics: animal-matched 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).