3914

Longitudinal simultaneous fMRI and mesoscale calcium imaging in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease1Radiology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 2Radiology and bioimaging sciences, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 3Douglas Mental Health University Institute, McGill, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 5Neurology and Neuroscience, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Brain

Multimodal neuroimaging plays an active role in understanding clinically accessible biomarkers of health and disease. Using simultaneous mesoscopic calcium imaging and BOLD-fMRI, we examine spontaneous activity in a GCaMP-positive mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)—longitudinally—at 4, 6, and 9 months. We find that both imaging modalities show early wide-spread changes in connectivity in AD compared to controls, with diverging trends at 6months. Intriguingly, these neuroimaging changes precede typical behaviour deficits. Further, preliminary evidence of cross-modal uncoupling hints at a complex relationship between excitatory neural activity (calcium imaging data), and the BOLD signal that is affected by AD-related progression.Introduction

The simultaneous acquisition of wide-field fluorescent calcium (WF-Ca2+) and fMRI data affords us the ability to examine the cell-type specific underpinnings of the clinically accessible BOLD signal. There is evidence, from us1 and others2, that WF-Ca2+ imaging of excitatory neural activity and BOLD fMRI (or hemodynamic signals) shows a high level of correspondence in healthy tissue. Here, we extend our application of multimodal imaging to investigate changes in spontaneous brain activity longitudinally in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). To accomplish this goal, we applied a new technique for viral vector delivery which circumvents costly cross-breeding of animals bearing the desired disease and fluorophore phenotypes3, and developed a head-plate preparation that accommodates our longitudinal study design. We uncover evidence of wide-spread changes in functional connectivity, from both modalities, that emerge before gross pathological changes and behavioural deficits. Preliminary evidence also suggests that AD-related changes in functional connectivity diverge across modalities as disease progresses compared to wild-type (WT) controls.Methods

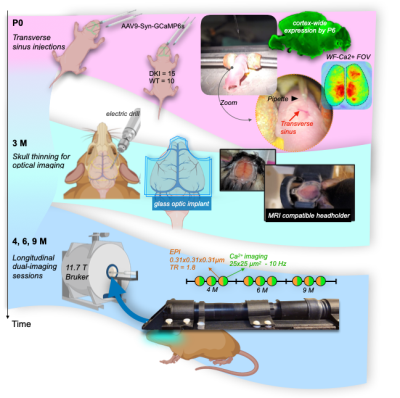

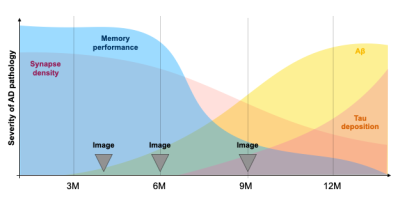

Experimental timeline, Fig.1.Mice. We use an amyloid-precursor-protein (APP) knock-in mouse model where amyloid-β-containing exons from human APP with the Swedish, Arctic and Iberian mutations have been included (APPNL-G-F)4. In addition, these mice were crossed with a strain in which the human microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) locus, with its full sequence and splice sites, has replaced the murine locus to generate APPNL-G-F/hMAPT homozygous double-knock-in (DKI) animals4. These mice develop plaques, synaptic density loss, phosphorylated Tau, and behavioural deficits (Fig.2).

Surgeries. Mice (NDKI=15, NWT=10) undergo two minimally invasive procedures (Fig.1, top and middle sections). (1) On postnatal day 0 (P0), mice are injected with AAV9-syn-GCaMP6s into the transverse sinuses2. This method of viral vector delivery imparts uniform whole-brain fluorescence by taking advantage of the underdeveloped blood-brain-barrier3. (2) At 3M, head-plates, for immobilization and optical access to the cortex, are affixed to the thinned but intact skull1. Animals recover for 1M before multimodal imaging.

MRI. Data were acquired on an 11.7T magnet (Bruker), under isoflurane, using a GE-EPI sequence TR/TE 1.8sec/9.1ms. Data were isotropic 0.31x0.31x0.31mm3. Each run was ~10mins (334 repetitions). In total, 30mins of data were acquired from each animal at each session. Additional structural images were acquired for multimodal registration1. Data were processed using RABIES (Rodent Automated BOLD improvement of EPI sequences)5.

WF-Ca2+ imaging. Concomitant with all fMRI recordings, WF-Ca2+ data were acquired (0.025x0.025mm2, at an effective 10Hz after baseline correction). Acquisition/processing was as we have described1,6.Data post-processing. Data were registered to a common-space using custom tools in BioImageSuite1. Connectivity matrices were computed using regions from the Allen Atlas7 and Pearson’s correlation. A T-test was computed to contrast groups (AD versus WT).

Results

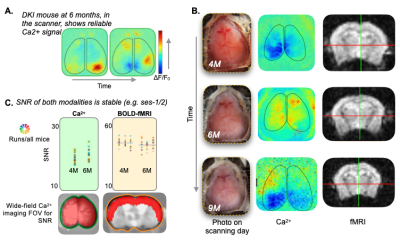

Transverse sinus injections of viral vectors work well in an AD model for WF-Ca2+ imaging. Here, we have successfully adopted and extended the transverse sinus injections method for viral vector delivery at P0 to a disease model (DKI, Fig. 3A). This approach accelerates the application of fluorescence imaging methods in models of human diseases by circumventing costly and time consuming cross-breeding. Here, N=25 mice were transfected with a 100% survival rate. Fluorophore signal was sufficient at 4, 6, and 9M for WF-Ca2+ imaging using our in-scanner optical set-up (Fig. 3B).Optically transparent implants for longitudinal WF-Ca2+ imaging. The WF-Ca2+ and fMRI signal-to-noise-ratio was stable (Fig.3C) throughout our protocol. This demonstrates the notable longevity of these implants. Whole-brain BOLD-fMRI connectivity shows AD-related changes at all timepoints. Relative to WT animals, we observe a decrease in connectivity in DKI mice at 4M (Fig.4, left). At 6M, this pattern reverses; DKI, relative to WT, mice show increased connectivity (Fig.4, middle). Finally, at 9M, the pattern flips again with DKI animals showing reduced connectivity relative to their WT counterparts (Fig.4, right). This triphasic trajectory indicates complex underlying changes in brain connectivity. Further, the emergence of differences in connectivity at 4M precedes evidence of gross pathology and behavioural differences (Fig.2).Cortical WF-Ca2+ imaging data also show AD-related changes in connectivity at early timepoints. AD, relative to WT mice, show changes in connectivity measured from fluorescently labelled excitatory neurons (Fig.5, top panel). At 4M, DKI, relative to WT, mice show globally decreased connectivity that becomes more pronounced at 6M.AD-related changes in connectivity do not show a simple intermodal relationship. Even when we consider just the BOLD-fMRI voxels that are within the cortex (match the field-of-view accessible to WF-Ca2+ imaging) (Fig.5, lower panel), we observe markedly different AD-related changes in connectivity across neuroimaging modalities. The different trajectories observed in these simultaneously acquired data are preliminary evidence of a complex relationship between these contrasts and the development of AD pathology.Conclusion

Through advancing the application of simultaneous multimodal neuroimaging, we uncover evidence of early AD-related changes in multimodal functional connectivity that precede typical behavioural changes. The ability to detect disease processes before potentially irreversible symptoms, has a clear clinical application: preventative treatments. Further, our preliminary analyses indicate an AD-related uncoupling of excitatory neural activity and BOLD. Pursuing this evidence may help uncover the cell-type specific underpinnings of BOLD-fMRI functional connectivity; a clinically accessible measure of brain function that is still poorly understood.Acknowledgements

Drs. Joel Greenwood and Omer Mano from Neurotechnology Core and Dr. Peter Brown from Magnetic Resonance Research Center Yale University for their technological expertise. Yale Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center Scholar’s Award Funding.References

1 - Lake EM, Ge X, Shen X, Herman P, Hyder F, Cardin JA, Higley MJ, Scheinost D, Papademetris X, Crair MC, Constable RT. Simultaneous cortex-wide fluorescence Ca2+ imaging and whole-brain fMRI. Nature methods. 2020 Dec;17(12):1262-71.

2 - Ma Y, Shaik MA, Kozberg MG, Kim SH, Portes JP, Timerman D, Hillman EM. Resting-state hemodynamics are spatiotemporally coupled to synchronized and symmetric neural activity in excitatory neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016 Dec 27;113(52):E8463-71.

3 - Hamodi AS, Sabino AM, Fitzgerald ND, Moschou D, Crair MC. Transverse sinus injections drive robust whole-brain expression of transgenes. Elife. 2020 May 18;9:e53639.

4 - Saito T, Mihira N, Matsuba Y, Sasaguri H, Hashimoto S, Narasimhan S, Zhang B, Murayama S, Higuchi M, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Humanization of the entire murine Mapt gene provides a murine model of pathological human tau propagation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2019 Aug 23;294(34):12754-65.

5 - Desrosiers-Gregoire G, Devenyi GA, Grandjean J, Chakravarty MM. Rodent Automated Bold Improvement of EPI Sequences (RABIES): A standardized image processing and data quality platform for rodent fMRI. bioRxiv. 2022 Jan 1.

6 - O'Connor D, Mandino F, Shen X, Horien C, Ge X, Herman P, Crair M, Papademetris X, Lake EM, Constable RT. Functional network properties derived from widefield calcium imaging differ with wakefulness and across cell type. bioRxiv. 2022 Jan 1.

7 - Wang Q, Ding SL, Li Y, Royall J, Feng D, Lesnar P, Graddis N, Naeemi M, Facer B, Ho A, Dolbeare T. The Allen mouse brain common coordinate framework: a 3D reference atlas. Cell. 2020 May 14;181(4):936-53.

Figures