3897

High permittivity ceramics for improving detection of fMRI activation at 1.5T

Vladislav Koloskov1, Mikhail Zubkov1, Georgiy Solomakha1, Viktor Puchnin1, Anatoliy Levchuk1,2, Alexander Efimtcev1,2, Irina Melchakova1, and Alena Shchelokova1

1School of Physics and Engineering, ITMO University, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation, 2Department of Radiology, Federal Almazov North-West Medical Research Center, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation

1School of Physics and Engineering, ITMO University, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation, 2Department of Radiology, Federal Almazov North-West Medical Research Center, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation

Synopsis

Keywords: Hybrid & Novel Systems Technology, Hybrid & Novel Systems Technology, high permittivity materials, SNR enhancement

We show that high permittivity materials (HPMs) can improve functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) at 1.5T, increasing the receive sensitivity of a commercial multi-channel head coil. Both numerical simulations and experiment showed ~25% improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of a commercial head coil in the areas of interest when HPM blocks were placed in proximity. This led to an increase in the detected motor cortex fMRI activation volume by an average of 56%, thus resulting in more accurate functional imaging at 1.5T.Introduction

Reliable determination of regions with neuron activation during fMRI may be hindered due to the electric noise, often comparable in magnitude to the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) contrast. Practically, this requires a higher SNR1,2. To further improve the SNR of local volume coils, one can use artificial structures, such as HPMs3,4 or metasurfaces5. In particular, HPM pads have already proven themselves as a method to extend the field of view (FOV) and to improve the detection of BOLD activation in the cerebellum at 7T6. Here, we investigate numerically and experimentally with healthy volunteers the effect of HPM pads on receive (Rx) sensitivity of a commercial multi-channel head coil to improve the detection of brain activation regions in the motor cortex fMRI at 1.5T.Methods

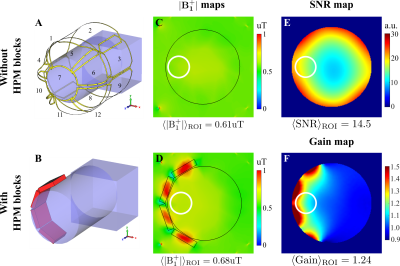

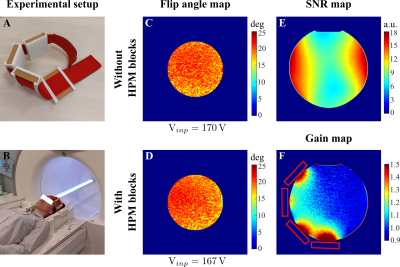

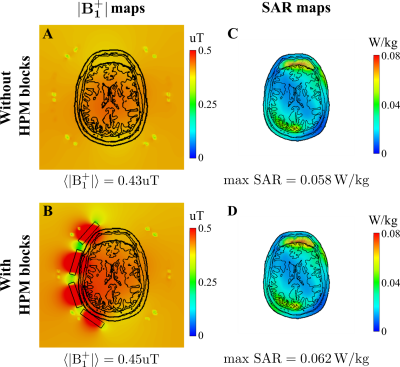

Electromagnetic (EM) simulations were performed in CST Microwave Studio 2021. To evaluate the transmit (Tx) efficiency and SNR, the following setups were considered: a whole-body birdcage coil (BC) and a receive-only multi-channel head coil with and without the HPM blocks in the presence of a homogeneous head phantom (Fig. 1A,B). The BC loaded with the phantom was matched and tuned to the working frequency at 63.64 MHz in the absence of the HPMs, the same was done with the head coil. Four HPM blocks4 based on BaTiO3 with permittivity ε=4500, tan δ=0.1 and dimensions of 57×71×13 mm3 were introduced into the models in single-side position relative to the phantom (Fig. 1B). MATLAB R2021b was used for SNR evaluation with passive blocks. In addition, to estimate the effect of the HPM blocks in fMRI, we performed EM simulations using a multi-slice head phantom. SNR maps were calculated without and with HPMs presence to obtain SNR gain maps for further fMRI simulations. Phantom imaging was performed on a whole-body 1.5T scanner (Magnetom Espree, Siemens) using the body BC in Tx mode and Siemens Head Matrix TIM coil in Rx mode. B1+ and SNR maps were obtained using a double-angle method7 with two gradient echo acquisitions and using data from one of the previous examinations divided by the standard deviation (SD) of noise in an MR image with no RF excitation, correspondingly. The homogeneity of the B1+-field distribution was calculated as the ratio of the SD of the angle value to its mean value. To investigate the radiofrequency safety with HPMs, simulations with a voxelized human body model placed in BC were performed. It was evaluated by as |B1+|RMS divided by max SARav.10g, where |B1+|RMS - the root mean squared value in the ROI, max SARav.10g – maximum local SAR averaged over 10 grams of tissues. The B1+-field and SAR distributions were normalized to 1W of the total accepted power. To investigate the impact of HPM blocks on the detection of neural activation in the motor cortex, we numerically simulated an fMRI study with a right-hand finger-tapping task using MATLAB-based STANCE toolbox7. fMRI experimental data were acquired for seven healthy volunteers with a right-hand finger-tapping task. To exclude the experiment order bias, the fMRI scans for three volunteers were performed first without blocks, then with blocks; for the remaining four volunteers, inverse order was used. Both numerical and experimental data were analyzed using group-level paired T-tests between acquisitions with and without HPM blocks in the MATLAB-based SPM toolbox8.Results

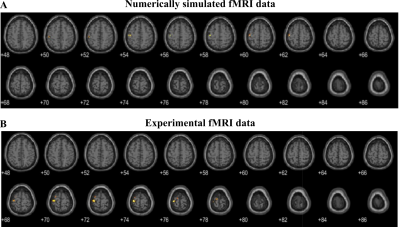

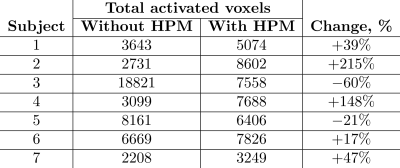

Figure 1C,D shows numerically calculated |B1+|RMS-maps for a homogeneous phantom placed inside BC without and with HPMs, correspondingly. HPM blocks led to a 12% Tx efficiency gain, whereas the SNR gain map demonstrated 24% enhancement in the ROI (Fig. 1F) in comparison to the reference case. Figure 2C,D showed an experimentally slight improvement of the Tx efficiency, insignificantly disturbing the B1+ homogeneity with HPM blocks in comparison to the reference case (91.2% versus 92.1%). The SNR gain map has a similar area of increase at the side of the phantom near the HPMs. Figure 3 demonstrates |B1+|RMS and SARav.10g maps for the human voxel model without and with HPMs. Similar to the phantom simulation’s results, one can observe an increase in the mean |B1+|RMS values with the presence of HPM blocks. The SAR efficiency with blocks was 1.09 uT/√W/kg compared to the reference case of 1.04 uT/√W/kg. The activation difference map between cases with blocks and cases without blocks for all volunteers, and the highest SNR simulations show statistically significant activation regions in the motor cortex for both numerical (Fig. 4, top two rows) and experimental (Fig. 4, bottom two rows) data. Figure 5 summarizes the results of fMRI experiments for all volunteers. The mean increase in the number of detected activation was 55% (from -60% to +215%).Discussion and conclusions

It was demonstrated that HPM blocks can inexpensively improve the detection of BOLD activation in lower clinical field MRI. Both simulation and experiment results showed an improvement in the Rx sensitivity of the dedicated RF coil, providing significant gain in detecting the BOLD contrast. This method can increase the utility of existing commercial head coils at 1.5T, leading to a more accurate mapping of functional brain regions.Acknowledgements

The part of the work related to the electromagnetic simulations and phantom studies was supported by a grant from the President of the Russian Federation for scientific school НШ-2359.2022.4. The part of the research devoted to the fMRI simulations and in vivo imaging was carried out with the support of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (075-15-2021-592).References

- Krüger G, et al. Neuroimaging at 1.5 T and 3.0 T: Comparison of oxygenation‐sensitive magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2001;45.4: 595-604.

- Fera F, et al. EPI‐BOLD fMRI of human motor cortex at 1.5 T and 3.0 T: Sensitivity dependence on echo time and acquisition bandwidth. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2004;19.1: 19-26.

- Webb A, et al. Novel materials in magnetic resonance imaging: high permittivity ceramics, metamaterials, metasurfaces and artificial dielectrics. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 2022:1-20.

- Zivkovic I, et al. High permittivity ceramics improve the transmit field and receive efficiency of a commercial extremity coil at 1.5 Tesla, Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2019;299:59–65.

- Schmidt R, et al. Flexible and compact hybrid metasurfaces for enhanced ultra high field in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Scientific reports 2017;7.1:1-7.

- Vaidya MV, et al. Improved detection of fMRI activation in the cerebellum at 7T with dielectric pads extending the imaging region of a commercial head coil, Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2018;48(2):431–440.

- Cunningham CH, et al. Saturated double‐angle method for rapid B1+ mapping. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2006;55.6:1326-1333.

- Hill JE, et al. A task-related and resting state realistic fMRI simulator for fMRI data validation, SPIE 2017;10133:748-759.

- Penny WD, et al. Statistical parametric mapping: the analysis of functional brain images, Elseiver;2011.

Figures

Figure 1: Numerical simulation setup: A, A head phantom placed inside Rx-only head coil; B, single-side placement of HPM blocks around the head phantom. C, D, Numerically calculated |B1+|RMS-maps normalized to 1W of total accepted power for a case without HPM blocks and with HPM blocks, respectively. E, Numerically calculated SNR map; F, SNR gain map for the setup in the presence of HPM blocks. White circles in panels C-F indicate the ROI, where |B1+|RMS, SNR, and SNR gain are calculated.

Figure 2: Experimental setup: A, A band with cases to fix the HPM blocks around the volunteer’s head. B, Photograph of the experimental setup with single-side HPM blocks around the volunteer’s head in an Rx-only head coil (only the bottom half of the coil is present in the image). Experimentally measured flip angle maps for the cases: C, without, and D, with HPM blocks placement. Experimentally measured E, SNR map for the reference case, and F, SNR gain map for the case with single-side HPM blocks placement.

Figure 3: Numerically calculated |B1+|RMS and SARav.10g maps for the voxel model inside whole-body birdcage coil A, C without and with B, D single-side HPM blocks placement, correspondingly. For each case, mean B1+ and maximum local SAR values were calculated in the slice crossing the center of HPM blocks with z=0. B1+ and SAR maps were normalized to 1 W of total accepted power.

Figure 4: fMRI activation maps show an improvement in functional activation in the motor cortex with HPM blocks in A, simulation, and B, experiment. Note that the activation areas might not coincide due to simulated data derived from single-subject data, while the experimental data shows the group-average contrast.

Figure 5: The total number of detected active voxels in the brain for each subject.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3897