3895

Low field Breast and Chest Wall Imaging for MR guided Proton Therapy

Neha Koonjoo1,2, Torben P.P Hornung1,2,3, Susu Yan3,4, Matthew S Rosen1,2,5, and Thomas R Bortfeld3,4

1Department of Radiology, A.A Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging / MGH, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Department of Physics, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, 4Department of Radiation Oncology, MGH, Boston, MA, United States, 5Department of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States

1Department of Radiology, A.A Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging / MGH, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Department of Physics, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, 4Department of Radiation Oncology, MGH, Boston, MA, United States, 5Department of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Low-Field MRI, Breast, Hybrid & Novel System Technology

The use of low field MRI guidance in proton therapy is a new area of research especially during treatment of breast cancer. In this study, we optimized and constructed five different breast/chest RF coils at low field as proof of concept for a future MR guided proton therapy system design. Different coil shapes and sizes were tested. Organs-at-Risk (OAR) and different anatomical regions were optimized for imaging. Using the five coils, phantom images were acquired at 6.5 mT and MR signal across slices were compared to the calculated optimized B1 field homogeneity. Human breast imaging was also carried out.Introduction

In the early 1990’s, designing efficient breast coils as a diagnostic tool for detecting human breast lesions at low field (< 1.0T) was of interest because of shorter T1 relaxation times and increased T1 tissue contrast1. Recent years, with the implementation of new hardware like improved magnetic gradient coil designs and amplifiers and in the hope of democratizing MR worldwide, low field MRI has gained even more interest2. While our goal is to design a hybrid system combining low field MRI and Proton Therapy for real-time breast cancer treatment, this study here focuses on the preliminary results of designing optimum breast RF coils having different shapes/sizes and wire winding patterns for both breast and chest wall imaging at ultra-low field. In that view, five different single channel breast-shaped coils were constructed, tuned/matched and 3D phantom imaging was conducted on a readily available scanner operating at 6.5 mT. The field homogeneity across the imaging volume were analyzed and SNR were compared among the different coils. One healthy female volunteer breast imaging was also carried out for the first time at 6.5 mT.Materials and Methods

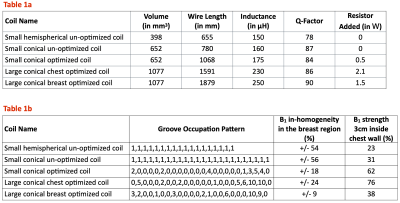

Coil designs and construction: A previous coil optimization method3 was further improved to adapt to any breast-shaped coil, imaging aim and a specific imaging region/volume requirement. Five different one channel volume breast coils were designed using CAD software (Fusion 360, Autodesk, USA) and 3D printed. Table 1a summarizes the characteristics of the five different coils which were labelled as follows: a) small hemispherical unoptimized coil, b) small conical unoptimized coil, c) small conical optimized coil, d) large conical chest optimized coil and e) large conical breast optimized coil. All the coils were wired and tuned to 276.18 kHz and matched to at least –35 dB measured on S11. The target Q-factor of the coils was between 78 to 90 to ensure that the coil passband is not narrower than the MRI readout bandwidth. This varies between coils owing to their different inductances. For fair SNR comparison between two specific coils, similar Q-factor values were achieved (see Table 1a). In Table 1b, B1 field inhomogeneity in the breast volume and B1 field strength 3cm inside the chest wall (for improved OAR imaging) relative to the target field of the breast volume were calculated by the optimization algorithm for each of the five breast coils.Data Acquisition and Reconstruction: All the phantom imaging was carried out using two 0.625 mg/ml CuSO4-DI solution-filled phantoms having either a hemispherical shape or a conical shape with a 3 cm base to simulate the chest wall. A 3D bSSFP sequence was used for imaging. The sequence parameters were as follows: acquired matrix size = 64×75, number of slices was 25 for conical coils and 20 for hemispherical coil, acquisition time were 14.2 minutes for conical coils and 12.5 minutes for hemispherical coil. The spatial resolution was kept the same for all the coils - 2.5 mm×3.5 mm×5.4 mm and NA=20. For each RF coil, the 10 repeated datasets were acquired and then reconstructed using 3D IFFT. One healthy female volunteer breast imaging was also carried out. The volunteer was in a standing position during the scanning. The 3D bSSFP sequence parameters were - matrix size: 64×75×15, spatial resolution = 2.5 mm×3.5 mm×8.5 mm, NA=40 and acquisition time = 16.7 minutes.

Image Analysis: To enable fair comparison between the different breast coils, the mean overall SNR was assessed in the entire volume of the phantom by calculating the mean signal in the phantom region divided by SD of the noise.

Results

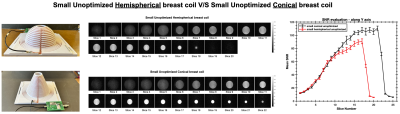

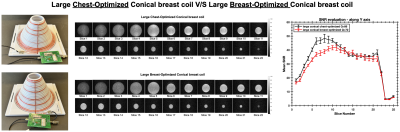

Figure 1 shows that even though the hemispherical-shaped former is a good match to the anatomical shape of the breast, the SNR is lower compared to the coil built on a more conical-shaped former. Of coils built in this conical shape, the optimized coil showed a more homogeneous B1 field with a homogeneous SNR across the different slices within the breast volume compared to the unoptimized coil (see Figure 2). As expected, the unoptimized coil showed higher intensities towards the peak of the coil. Since the optimized coil has a higher inductance, the coil bandwidth was broadened with a 0.5 Ω resistor, hence increasing the noise level and reducing the overall SNR. In Figure 3, the optimization algorithm was tested for a larger size coil and for different anatomical regions. The SNR across different slices for breast-optimized coil were consistent along the entire breast volume. For the chest-optimized coil, the SNR was higher at the base of the coil on the first 10 slices and then the SNR dropped to that of the breast-optimized coil. All the imaging results corroborate with the calculated B1 field homogeneity in Table 1b. Finally, Figure 4 shows the first breast images at 6.5 mT of a healthy female volunteer using either the breast-optimized coil or the chest-optimized coil.Discussion and Conclusion

The observed B1 field homogeneity, the relative ratio of the SNRs for all the five breast coils, and the stronger signal in the chest are in good agreement with the simulations. Further human breast imaging shall be carried out using the different optimized coils as well as different imaging positions shall be explored.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH R21CA267315-01A1. MSR acknowledges support of the Kiyomi and Ed Baird MGH Research Scholar award.References

1. Komu, M. and Kormano, M. (1992), Breast coil design for low-field mri. Magn. Reson. Med., 27: 165-170.

2. Marques, J.P., Simonis, F.F. and Webb, A.G. (2019), Low-field MRI: An MR physics perspective. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 49: 1528-1542.

3. Shen S, Xu Z, Koonjoo N, Rosen MS. Optimization of a Close-Fitting Volume RF Coil for Brain Imaging at 6.5 mT Using Linear Programming. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2021;68(4):1106-1114.

Figures

Table 1: a) Characteristics of the five single channel breast coils. b) The groove occupation pattern for each of the five breast coils, the calculated B1 field homogeneity in the breast volume and the calculated B1 field strength in chest region relative to the target field strength in the breast volume (using the optimization algorithm)

Figure 1: Comparison between hemispherical and conical breast coils – from left to right: Picture of the hemispherical coil (top) and picture of the conical coil (bottom). Both coils were unoptimized with an evenly spaced groove occupation pattern. Phantom images were acquired keeping the same spatial resolution. The graph shows the mean SNR across slices obtained with either the hemispherical coil (in red) or the conical coil (in black). The graph shows that the conical coil is more efficient.

Figure 2: Comparison between unoptimized and optimized conical breast coils – from left to right: Picture of unoptimized coil with evenly spaced groove occupation pattern (top) and picture of optimized coil with a specific groove occupation pattern (bottom). Phantom images show a more homogeneous signal across slices with the optimized coil. The mean SNR analysis across slices obtained with either the unoptimized coil (in black) or the optimized coil (in red) shows that the optimized conical coil has a higher B1 field homogeneity with lower SNR compared to the unoptimized coil.

Figure 3: Comparison between chest-optimized and breast-optimized conical breast coils – from left to right: Picture of the chest-optimized coil (top) and picture of the breast-optimized coil (bottom). Phantom images were acquired with the same imaging parameters. The overall mean SNR across the different slices were calculated for both coils: the chest-optimized coil (in black) or the breast-optimized coil (in red). The SNR evaluation shows a higher SNR at the base of the coil for the chest-optimized coil compared to a homogeneous plateau for the breast-optimized coil.

Figure 4: Human breast imaging using either the breast-optimized (top panel) or the chest-optimized (bottom panel) large conical breast coils.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3895