3884

Implicit CINE: a deep-learning super-resolution model for multi-planar real-time MRI1IADI, Université de Lorraine, INSERM U1254, Nancy, France, 2Institut für Medizinische Informatik, Universität zu Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany, 3CIC-IT, INSERM 1433, Université de Lorraine and CHRU Nancy, Nancy, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Cardiovascular

Cardiac CINE MRI plays an essential role in cardiac diagnosis, but not all patients are eligible for 3D imaging, which is associated with long acquisition times. We propose a deep-learning super-resolution model to generate 3D CINE from multi-planar 2D real-time MRI using external signals for cardiac and respiratory motion estimation. The proposed neural field model is trained on a single subject and performs non-rigid motion compensation and implicit representation learning in an end-to-end manner. A preliminary study with three healthy volunteers demonstrates promising reconstruction performance and computation times compared to traditional registration-based approaches.Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death globally, and arrhythmias are the main cause of sudden cardiac death1,2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is key for improving the diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias as it enables the assessment of cardiac morphology and function. While successful free-breathing 3D+t MRI reconstruction algorithms were proposed for normal heart rhythms3, the imaging of pathological beats is an unmet need as it requires the acquisition of multiple heart beats to achieve CINE images with full heart coverage. We study a reconstruction post-processing model that combines stacks of free-breathing, multi-planar 2D real-time MRI to a super-resolved 3D+t CINE using external motion signals as guidance. The proposed neural field provides a continuous, implicit representation of the subject heart by learning a consistent mapping from 5D input coordinates (3D location, cardiac phase, and respiration phase) to 1D intensity values that best reconstructs the pixels of the acquired 2D MRI frames. During inference, the continuous model can reconstruct isotropic volumes at arbitrary resolutions. Neural fields became particularly popular for novel scene synthesis in computer vision4 but also gained attention in medical imaging with promising performance in static super-resolution5 and implicit volume reconstruction6. Dynamic neural fields7 use a decoupled motion estimation which facilitates the explicit regularization of spatial and temporal consistency. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to explore neural fields for the super-resolution of cardiac CINE MRI.Methods

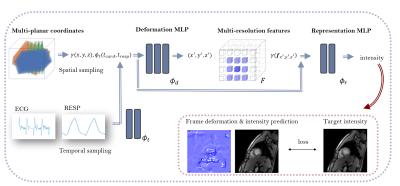

We study a dataset of three healthy subjects with real-time FLASH gradient echo MRI8 scanned in one short axis (SAX) and two long axis (LAX) views at a resolution of 20ms (TR/TE: 2.22-2.42/1.46ms, flip angle: 8°, bandwith: 1470, FOV: 296x296). The spatial resolution was $$$1.48\times1.48\times6-8$$$ mm and each view-plane stack consisted of 8 to 21 slices with 60 to 80 temporal frames. ECG signals were used for cardiac synchronization9, and respiration signals were estimated from the ECG using a low-pass filter. We compared four super-resolution models that were optimized for each subject individually: static super-resolution reconstruction as proposed by Odille et al.10 using rigid slice registration and Beltrami regularization to solve for an isotropic volume per cardiac phase (‘Beltrami’), rigid slice-to-volume registration and super-resolution using SVRTK11 (‘SVRTK’), a baseline neural field learning a direct 5D to 1D mapping (‘neural field’), and a dynamic neural field with explicit motion field estimation (‘dynamic neural field’). Figure 1 demonstrates the dynamic neural field architecture which consists of two multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) $$$\phi_d$$$ for the deformation field prediction, and $$$\phi_r$$$ for the representation learning. The networks $$$\phi_d$$$ and $$$\phi_r$$$ use ReLU activation functions and consist of three and two fully connected layers with 128 neurons, respectively. To reduce the bias towards low-frequency features, network inputs are passed through a positional encoding function. As proposed in 12, we encode the temporal inputs $$$t_{card}$$$ and $$$t_{resp}$$$ using a two-layer time-enhancement MLP $$$\phi_t$$$ and sample feature vectors $$$\mathbf{f}^{x,y,z}\in \mathbb{R}^{C}$$$ from a trainable grid $$$F\in \mathbb{R}^{C,N_x,N_y,N_z}$$$ using interpolation at three resolutions to speed up convergence. The grid sizes $$$N_x,N_y,N_z$$$ are increased in the course of training to achieve coarse-to-fine learning. The neural fields are optimized end-to-end using Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, exponential learning rate scheduling, MSE loss, and total variation grid regularization. We furthermore finetune the networks using a combination of MSE and LPIPS loss13.Results

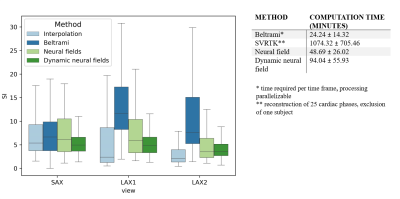

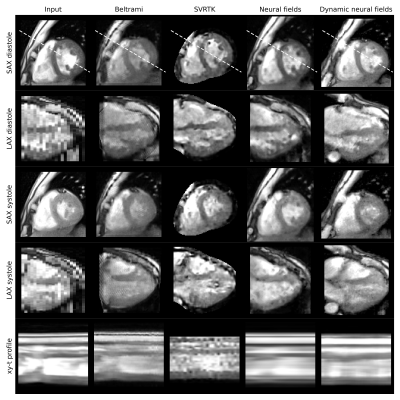

In this preliminary work, isotropic reconstruction quality was assessed visually and quantitatively, using the Sharpness Index (SI)14 as a non-reference metric. Figure 2 demonstrates that promising slice shift correction was observed for the proposed models. From the intensity profiles it can be seen that the contraction of the ventricles were better modelled by the dynamic neural field than by the baseline neural field, which under-estimated the cardiac motion. Best SI scores were achieved by the Beltrami model. Computation times are summarized in figure 3.Discussion

Despite complex architecture and long computation time, the SVRTK model demonstrated the worst performance, producing spatially inhomogeneous predictions. Even though the Beltrami model was optimized per cardiac phase, it demonstrated the most consistent intensity profiles. However, its rigid slice registration could not fully resolve respiratory motion shifts, with superior LAX reconstructions being observed for the neural fields with non-linear motion estimation. Using decoupled motion estimation in the dynamic neural field appeared to improve the reconstruction of the systolic phase, whose motion was under-estimated by the baseline neural field. While conditioning the network on $$$t_{card}$$$ and $$$t_{resp}$$$ could guide the disentanglement of cardiac and respiratory motion, other sources of motion were currently neglected. Our future work will focus on improving the supervision of the deformation model. We will, furthermore, explore synthetic datasets for quantitative evaluation with ground-truth knowledge, assess radiology scoring, and explore hypernetworks15 to avoid learning networks from scratch for every subject.Conclusion

The proposed dynamic neural field model optimizes motion estimation and super-resolution simultaneously and is thus able to exploit temporal and spatial redundancies for learning a consistent heart representation. Our findings suggest that neural fields show potential for 3D CINE reconstruction of abnormal rhythms as the models can be trained on flexible numbers of input frames and incorporate the information from external sensors, enabling real-time detection and processing of abnormal rhythms.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the ERA-CVD Joint Translational Call 2019, MEIDIC-VTACH (ANR-19-ECVD-0004).References

1. Global health estimates 2019: Life expectancy and leading causes of death and disability, 2000–Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/theme-details/GHO/mortality-and-global-health-estimates, accessed 31 October 2022).

2. Mehra R. Global public health problem of sudden cardiac death. Journal of electrocardiology 2007; 40(6): 118-122.

3. Menini A, Vuissoz P A, Felblinger J, et al. Joint reconstruction of image and motion in MRI: implicit regularization using an adaptive 3D mesh. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 2012; 264-271.

4. Mildenhall B, Srinivasan P P, Tancik M, et al. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Communications of the ACM 2021; 65(1): 99-106.

5. Wu Q, Li Y, Xu L, et al. Irem: High-resolution magnetic resonance image reconstruction via implicit neural representation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 2021; 65-74.

6. Yeung P H, Hesse L, Aliasi M, et al. ImplicitVol: Sensorless 3D Ultrasound Reconstruction with Deep Implicit Representation; 2021.

7. Pumarola A, Corona E, Pons-Moll G, et al. D-nerf: Neural radiance fields for dynamic scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2021; 10318-10327.

8. Uecker M, Zhang S, Voit D, et al. Real-time MRI at a resolution of 20 ms. NMR in Biomedicine 2010; 23(8): 986-994.

9. Isaieva K, Fauvel M, Weber N, et al. A hardware and software system for MRI applications requiring external device data. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2022.

10. Odille F, Bustin A, Chen B, et al. Motion-corrected, super-resolution reconstruction for high-resolution 3D cardiac cine MRI. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 2015; 435-442.

11. Van Amerom J F, Lloyd D F, Deprez M, et al. Fetal whole-heart 4D imaging using motion-corrected multi-planar real-time MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2019; 82(3): 1055-1072.

12. Fang J, Yi T, Wang X, et al. Fast Dynamic Radiance Fields with Time-Aware Neural Voxels; 2022.

13. Zhang R, Isola P, Efros A A, et al. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 2018; 586-595.

14. Blanchet G, and Moisan L. An explicit sharpness index related to global phase coherence. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing 2012; 1065-1068.

15. Sitzmann V, Zollhöfer M, and Wetzstein G. Scene representation networks: Continuous 3d-structure-aware neural scene representations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32; 2019.

Figures

Figure 2: Qualitative results for an example case showing a SAX and a LAX plane of the compared model outputs at two cardiac phases. The bottom row shows the intensity profile across cardiac phases. The profile is visualized as a white, dashed line in the SAX diastole plane. Note that the models used different regions of interest during optimization (intersecting region, cardiac segmentation region, and cardiac bounding box for Beltrami, SVRTK, and neural fields, respectively). As SVRTK failed to generate a solution for one of the cases, it was excluded from the quantitative evaluation.