3880

Deep Learning Reconstruction of Dynamic Free-breathing Fetal Heart MRI to Improve Clinical Pipeline1Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Department of Informatics, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 3Department of Computing, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Image Reconstruction

Dynamic free-breathing fetal heart MRI requires high spatial and temporal resolution, which could be reconstructed by kt-SENSE from undersampled data guided by priors of the same anatomy. Doubled acquisition time and uncontrolled fetal motion between the 2 acquisitions affects the data quality for reconstruction. We explored an alternative deep learning approach using a 3D U-Net based model with time-averaged skip connection and data consistency. Assessment of the model set a baseline for prior preconstruction and underlines important pitfalls that will drive further improvements to achieve optimal reconstruction quality.Introduction

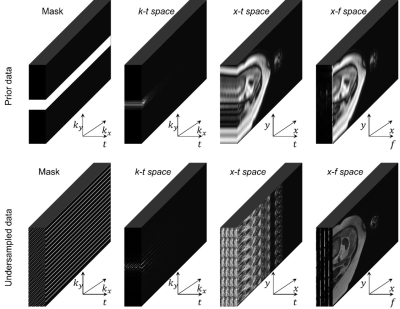

Dynamic free-breathing fetal cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (fcMRI) requires high spatial and temporal resolution to depict tiny structures and capture uncontrolled fetal motion as well as cardiac beating, which could be more than twice as fast as an adult heartbeat. A kt-SENSE approach1 can reconstruct dynamic fcMRI from acquired prior and undersampled sets shown in Figure 1. However, the required data doubles the acquisition compared to conventional cardiac imaging, and subject movement between the prior and undersampled sections can introduce inconsistency that degrades reconstruction.In this work, we explore and assess deep learning (DL) models to recover the prior from undersampled data focusing on dynamic features of fcMRI to try to eliminate the problem of motion between acquisition stages and accelerate the overall acquisition procedure and assess performance.

Methods

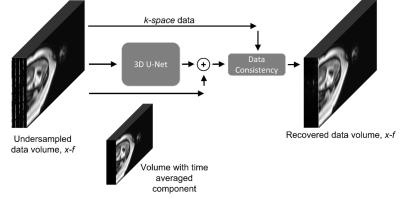

We study a U-Net2 like baseline model and recent state-of-the-art CTFNet3 in application to fcMRI reconstruction. An available fcMRI dataset with 55809 dynamic 3D coil volumes of fully-sampled prior with size 64x19x400 for 56 patients allows us to train the models to recover retrospectively undersampled data with acceleration factor 8.The baseline model in Figure 2 is a 3D U-Net2 upgraded with time-averaged skip connection and data consistency3-5, which operates in x-f domain, where data has a more sparse representation. To shift the optimisation from large values in the mean image onto reconstruction of dynamic features, the time averaged component is directly added to output, similarly to k-t SENSE1. Data consistency helps to enforce values where sampled3-5.

We use the baseline model to recover full data directly from the undersampled coil signal or augmented with short snippet (8 frames) of coil-combined fully-sampled data, zero-filled to match the size of the input, as an additional input channel to provide temporal context. Although the use of snippet keeps the prior acquisition in the pipeline, it requires much shorter acquisition. Both versions were trained by Adam6 optimiser on coil data normalised to the same noise level for 50 epochs with L1 loss functions.

As a gold standard we used CTFNet3 a state-of-the-art network designed for dynamic adult heart MRI, which mimics the k-t SENSE1 algorithm. The CTFNet is trained for 150 epochs on patched coil fetal data and sensitivity maps using Adam6 optimiser with L1 loss function similarly to the original implementation.

For all networks, performance was assessed using normalised mean squared error (NMSE) with respect to the fully sampled coil-combined ground truth testing dataset and reviewed qualitatively in the both the time and temporal frequency domains.

Results

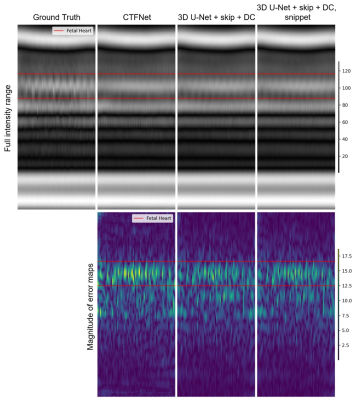

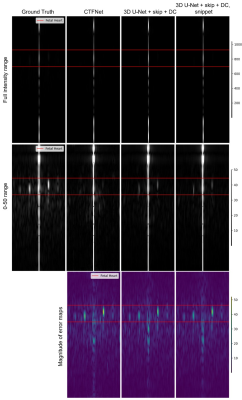

The quantitative assessment showed that both variants of 3D U-Net with time average skip connection and data consistency delivered the best performance with NMSE of 0.003, compared to 0.0052 for the CTFNet model.Figure 3 shows that all trained models deliver image frame representations of similar quality with overall anatomy structure recovered well. However, the models do not fully recover dynamic areas such as maternal blood vessels and fetal heart. Figures 4 and 5 show reconstructions of the fetal heart plane along time and temporal frequency axes, we observe excellent reconstruction quality for static anatomy and slowly changing parts. In the case of rapid changes such as periodic fetal cardiac motion, they do less well underestimating the amplitude of higher frequency harmonics with clear errors concentrated in these regions. As expected from the NMSE measure, the variants of 3D U-Net deliver similar reconstructions in these areas, and these are closer to the ground truth than CTFNet prediction.

Discussion

Our results show that all models recover static and slowly changing regions of fcMRI. Although, both variants of 3D U-Net with time-averaged skip connection and data consistency baseline model outperformed the recent CTFNet in terms of estimating the dynamics of fetal heart and maternal blood vessels, they still do not fully recover dynamic of fetal heart and maternal blood vessels, while including the snippet appears to provide only a marginal benefit.The dynamic fcMRI is probably more challenging than adult cardiac imaging, because the signal-to-noise ratio is lower and the dynamic region is a very small part of the field of view, making it a weak feature for training even the cutting-edge CTFNet. Paradoxically, the very feature of dynamic content occupying only a very small part of the imaged scene allowed kt-SENSE to be so successful might be a reason for poor performance of DL methods in this application. There remain obvious potential benefits for a DL approach for replacing the prior data, but further work will be needed to realise these.

Conclusion

Our work explored a new approach to dynamic fcMRI to improve overall clinical dynamic fetal cardiac MRI procedure. While the proposed DL approach unlocks reconstruction of densely sampled prior from undersampled data replacing the acquisition of the prior accelerating acquisition procedure and eliminating inconsistencies between 2 acquisitions, it faces the properties of fetal heart data making the task more challenging than expected. Our results show the performance baseline DL models and the pitfalls of the problem helping to drive further upgrades for fcMRI reconstruction and improving following studies of fetal heart development7,8.Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge funding from the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Smart Medical Imaging (EP/S022104/1).

References

1.Tsao, Jeffrey, Peter Boesiger, and Klaas P. Pruessmann. "k‐t BLAST and k‐t SENSE: dynamic MRI with high frame rate exploiting spatiotemporal correlations." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 50.5 (2003): 1031-1042.

2. Ronneberger, Olaf, Philipp Fischer, and Thomas Brox. "U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation." International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, Cham, 2015.

3. Qin, Chen, et al. "Complementary time‐frequency domain networks for dynamic parallel MR image reconstruction." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 86.6 (2021): 3274-3291.

4. Schlemper, Jo, et al. "A deep cascade of convolutional neural networks for MR image reconstruction." International conference on information processing in medical imaging. Springer, Cham, 2017.

5. Qin, Chen, et al. "k-t NEXT: dynamic MR image reconstruction exploiting spatio-temporal correlations." International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, Cham, 2019.

6. Kingma, Diederik P., and Jimmy Ba. "Adam: A method for stochastic optimization." arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

7. van Amerom, Joshua FP, et al. "Fetal whole‐heart 4D imaging using motion‐corrected multi‐planar real‐time MRI." Magnetic resonance in medicine 82.3 (2019): 1055-1072.

8. Roberts, Thomas A., et al. "Fetal whole heart blood flow imaging using 4D cine MRI." Nature communications 11.1 (2020): 1-13.

Figures