3849

Bayesian and lagged general linear modelling strategies in breath-hold induced cerebrovascular reactivity mapping with muti-echo BOLD fMRI1Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2Basque Centre on Cognition, Brain and Language, Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain, 3Sir Peter Mansfield Imaging Centre, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI, Blood vessels, Cerebrovascular reactivity

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR), the ability of blood vessels to dilate and constrict in response to a vasoactive stimulus, is an important indicator of cerebrovascular health and can be estimated using BOLD functional MRI. In this work, we evaluated a novel variational Bayesian method for mapping CVR dynamics which yielded similar CVR results and reproducibility to a time-shifted, “lagged” general linear model approach, and uncovered the need for more research into negative CVR. This novel approach is more time efficient and has the potential to improve CVR mapping by incorporating non-linear modelling and physiologically meaningful information (in the form of priors).Introduction

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) reflects the intrinsic mechanism of blood vessels to alter their calibre in response to a vasoactive stimulus (e.g. a change in arterial CO2 content). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) based on blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) contrast acquired during breath-hold (BH) tasks is a non-invasive, robust method to derive CVR maps1, being increasingly used to assess various pathologies, including cerebrovascular diseases2, brain tumours3, and neurodegenerative disorders4. CVR is commonly quantified by its amplitude changes, but temporal features might provide information of interest. One way of retrieving both the temporal and amplitude information is by using a lagged general linear model with time-shifted regressors (lGLM)5. Recently, a variational Bayesian (VB) approach has been applied to CVR, allowing for non-linear model fitting and the incorporation of priors6. In this study, we evaluate the performance of these two methods on multi-echo BOLD fMRI data, acquired in ten subjects performing a BH task during ten repeated sessions7, to obtain subject-specific CVR and haemodynamic delay estimates, and their corresponding reproducibility metrics.Methods

Multi-echo BOLD fMRI data was acquired in ten subjects performing a BH task during ten sessions (3T Siemens PrismaFit; 340 scans, TR=1.5s, TEs=10.6/28.69/46.78/64.87/82.96ms, FA=70°, multiband=4, GRAPPA=2 with gradient echo reference scan, 52 slices with interleaved acquisition, Partial Fourier=6/8, voxel size=2.4×2.4×3mm3)7. The task involved eight repetitions of four paced breaths (6s each), a 20s BH, 3s exhalation, followed by a recovery period (11s without pacing)8. Partial pressure of end-tidal CO2 (PETCO2) levels were acquired throughout1. Four subjects were excluded due to poor BH performance. MRI data processing was performed using AFNI9, FSL10, and ANTS11, including multi-echo T2*-weighted combination12, followed by nuisance regression of up to fourth-order Legendre polynomials, parameter realignment, and temporal derivatives. The PETCO2 time-courses were processed and the end-tidal peaks selected (Python 3.6.7). The CVR toolbox in Quantiphyse13 was used for the lGLM and VB analyses to estimate the CVR amplitude and delay maps6 for each session/subject. To account for measurement delay, Quantiphyse applied a bulk shift to each PETCO2 trace to maximise its cross-correlation with the average whole-brain fMRI signal. We established a window for the candidate delays of ±8s from the bulk shift with a 1s timestep for the lGLM approach, whereas this information is not required in the VB approach. The estimated CVR maps were scaled to BOLD change over the change in PETCO2 (%BOLD/mmHg). The delay maps were centred with respect to the session-specific average delay within the brain’s voxels. To compare the results, the maps were transformed to the MNI152 template (nearest neighbour interpolation)14. A linear mixed effects (LME) model was then applied voxel-wise, taking into account variability within and across subjects15. An intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC(2,1)) was also computed voxel-wise for the standardised CVR and delay maps using AFNI’s 3dICC to assess each method’s reproducibility16, considering 6 subjects and 10 sessions per subject.Results and Discussion

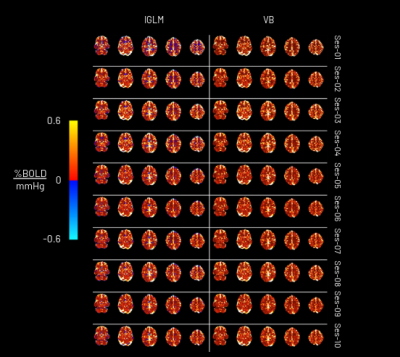

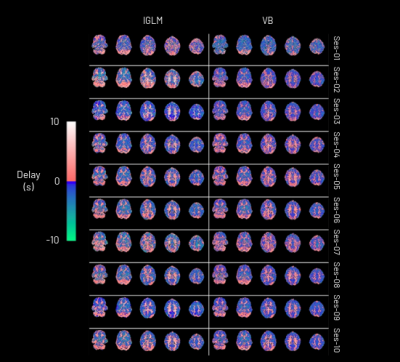

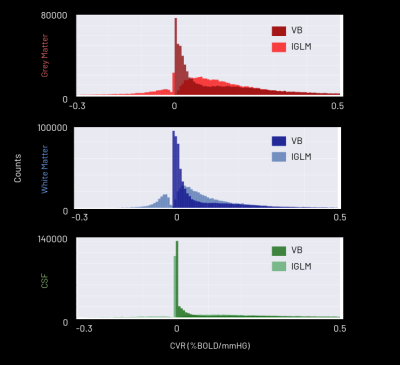

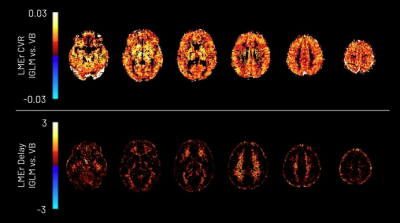

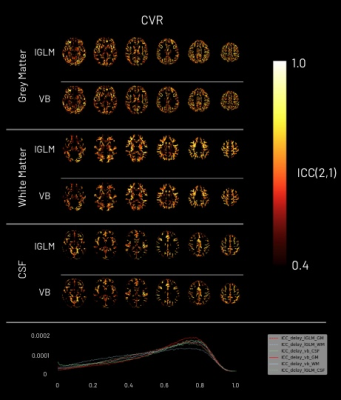

The CVR amplitude and delay maps derived for each session for one representative subject are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively, for each method. The CVR values in GM are highly comparable between methods and to previously reported values7. Notably, the lGLM approach reports negative CVR values, mostly in WM and ventricles CSF voxels, while the VB does not due to its non-negative prior on CVR amplitude as displayed in Figure 3. This negative CVR might originate from inaccurate modelling in noisy voxels with reduced CVR-related changes, the effect of “vascular steal”, and/or CSF flow and volume changes17. Figure 4 highlights statistically significant differences between methods in specific regions (e.g., WM and CSF). No significant differences were observed across grey matter. The high ICC scores (>0.6) in the CVR amplitude maps (Figure 5) indicate a high reproducibility with higher inter-subject variability than intra-subject variability in both methods. These ICC scores are lower than those reported in a previous work7, which applied ME-ICA denoising, simultaneous modelling and considered a finer time step for the lGLM approach, which warrants further investigation on the effect of these preprocessing and modelling choices, particularly for the VB approach. The lGLM approach was found to be less robust to noisy PETCO2 data when the automated bulk shift estimation is inaccurate since no shifting outside of the defined delay bounds is considered. Furthermore, the VB method can be more time efficient at scale as it fits the CVR amplitude and delay simultaneously, while the lGLM assesses the CVR amplitude for multiple delay values. These strategies offer robust quantification of CVR and can be particularly relevant for assessing patients with diseases where cerebral haemodynamics might be compromised.Conclusion

lGLM and VB modelling strategies provide robust CVR amplitude and delay maps for breath-hold BOLD fMRI data. Due to the priors incorporated in Bayesian regression, the VB analysis may provide a more accurate functional assessment of BOLD signals than the lGLM approach and may perform faster when high temporal resolution in the delay maps is necessary. More research is still required to better understand the physiology and implications behind negative CVR in BOLD fMRI. Future work will include testing different VB priors, including negative values.Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Clarendon Fund, the EPSRC

(EP/S021507/1), the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness

(RYC-2017-

415 21845), the Basque Government (BERC 2018-2021, PIB_2019_104), the

Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities

(PID2019-105520GB-100), and the GliMR 2.0 COST Action (CA18206).

References

[1] Pinto J, Bright MG, Bulte DP, Figueiredo P. Cerebrovascular Reactivity Mapping Without Gas Challenges: A Methodological Guide. Front Physiol. 2021;11. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.6084752.

[2] Webster MW, Makaroun MS, Steed DL, Smith HA, Johnson DW, Yonas H. Compromised cerebral blood flow reactivity is a predictor of stroke in patients with symptomatic carotid artery occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(2):338-345. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(95)70274-13.

[3] Pillai JJ, Zacá D. Clinical utility of cerebrovascular reactivity mapping in patients with low grade gliomas. World J Clin Oncol. 2011;2(12):397-403. doi:10.5306/wjco.v2.i12.3974.

[4] Glodzik L, Randall C, Rusinek H, Leon MJ de. Cerebrovascular Reactivity to Carbon Dioxide in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35:427-440. doi:10.3233/jad-1220115.

[5] Moia S, Stickland RC, Ayyagari A, Termenon M, Caballero-Gaudes C, Bright MG. Voxelwise optimization of hemodynamic lags to improve regional CVR estimates in breath-hold fMRI. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc Annu Int Conf. 2020;2020:1489-1492. doi:10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.91762256.

[6] Chappell MA, Groves AR, Whitcher B, Woolrich MW. Variational Bayesian Inference for a Nonlinear Forward Model. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2009;57(1):223-236. doi:10.1109/TSP.2008.20057527.

[7] Moia S, Termenon M, Uruñuela E, et al. ICA-based denoising strategies in breath-hold induced cerebrovascular reactivity mapping with multi echo BOLD fMRI. NeuroImage. 2021;233:117914. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.1179148.

[8] Bright MG, Murphy K. Reliable quantification of BOLD fMRI cerebrovascular reactivity despite poor breath-hold performance. NeuroImage. 2013;83:559-568. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.0079.

[9] Cox RW. AFNI: Software for Analysis and Visualization of Functional Magnetic Resonance Neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162-173. doi:10.1006/cbmr.1996.001410.

[10] Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. NeuroImage. 2012;62(2):782-790. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.01511.

[11] Tustison NJ, Cook PA, Klein A, et al. Large-scale evaluation of ANTs and FreeSurfer cortical thickness measurements. NeuroImage. 2014;99:166-179. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.04412.

[12] Posse S, Wiese S, Gembris D, et al. Enhancement of BOLD-contrast sensitivity by single-shot multi-echo functional MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42(1):87-97. doi:10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199907)42:1<87::aid-mrm13>3.0.co;2-o13.

[13] Quantiphyse — Quantiphyse 0.31 documentation. Accessed November 5, 2022. https://quantiphyse.readthedocs.io/en/v0.6/README.html14.

[14] Grabner RH, Neubauer AC, Stern E. Superior performance and neural efficiency: The impact of intelligence and expertise. Brain Res Bull. 2006;69(4):422-439. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.02.00915.

[15] Chen G, Saad ZS, Britton JC, Pine DS, Cox RW. Linear mixed-effects modeling approach to FMRI group analysis. NeuroImage. 2013;73:176-190. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.04716.

[16] Chen G, Taylor PA, Haller SP, et al. Intraclass correlation: Improved modeling approaches and applications for neuroimaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(3):1187-1206. doi:10.1002/hbm.2390917.

[17] Poublanc J, Han JS, Mandell DM, et al. Vascular Steal Explains Early Paradoxical Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Cerebrovascular Response in Brain Regions with Delayed Arterial Transit Times. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2013;3(1):55-64. doi:10.1159/00034884118.

Figures