3844

Using PINS pulses to saturate inflow effects from slice gaps in functional MRI

Shota Hodono1, Chia-yin Wu1,2,3, Carl Dixon1, Donald Maillet1, Jin Jin4, Jonathan R Polimeni5,6, and Martijn A Cloos1

1Centre for Advanced Imaging, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia, 2ARC Training Centre for Innovation in Biomedical Imaging Technology, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Australia, 3chool of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Australia, 4Siemens Healthcare Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Australia, 5Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 6Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

1Centre for Advanced Imaging, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia, 2ARC Training Centre for Innovation in Biomedical Imaging Technology, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Australia, 3chool of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Australia, 4Siemens Healthcare Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Australia, 5Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 6Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI, Velocity & Flow

In this work, we demonstrate the use of PINS pulses to mitigate unwanted inflow effects in 2D multi-slice sequences. A PINS pulse was played prior to slice-selective excitation to saturate the magnetization within all slice gaps. Bloch simulation and flow-phantom experiments show inflow effects can be removed completely. Functional scans using twice-refocused spin echo suggest that inflow effects may have noticeable contributions to SE-BOLD fMRI response. This PINS implementation allows us to further understand fMRI signal dynamics by modulating the inflow effect.introduction

Multi-slice acquisitions often use a slice gap to avoid cross-talk between adjacent slices1. However, the steady-state longitudinal magnetization in these gaps is can be substantially larger than in the slices themselves. Consequently, when fluids such as blood and cerebral spinal fluid move from these gaps into an image slice their large magnetization can cause a pronounced increase in signal. In some situations, inflow effects can be a desirable source of contrast2-5, in others it is a source of artifacts and bias6,7. In this study, we demonstrate that Power Independent of Number of Slices (PINS) pulses8,9 can be used to efficiently saturate the magnetization in the slice gaps. The proposed concept was evaluated using Bloch simulations, a flow phantom experiments, and in vivo in the brain.Methods

The PINS pulse is an undersampled sinc pulse, designed such that the produced aliasing pattern excites an infinite stack of gapped slices8,9. In this study, PINS pulses were designed to saturate the longitudinal magnetizations in all slice gaps. To demonstrate its use, the PINS module was incorporated into a twice-refocused spin-echo (TRSE) sequence (Fig.1). Since the PINS pulse is played before every excitation pulse (Fig.1) within each volume TR, all slice gaps ‘see’ the saturation pulse N/M times, where N is the number of slices and M is the multiband factor. Because all gaps are saturated multiple times per TR, it should be possible to efficiently and effectively saturate the inflow of fresh magnetization. All experiments were performed using a 3T MAGNETOM Prisma(Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 64-Ch head coil.Slice profile simulations validations: Bloch simulations were performed to evaluate the available longitudinal magnetization before the excitation pulse in a TRSE sequence with and without PINS saturation module. In addition, the ‘saturation’ profile was experimentally measured in a phantom. During these experiments the excitation slice was shifted ±6 mm from isocenter without moving the PINS pulse. The acquired MRI signal was then plotted as a function of the shift distance. The PINS pulse parameters are reported in the Fig.1 caption.

Flow phantom scan: To evaluate saturation of inflow, a home-built cylindrical flow phantom10 was scanned (Fig.3b). Three scans were compared: SE without slice gap, SE with a 50% slice gap, and PINS-SE with a 50% slice gap.

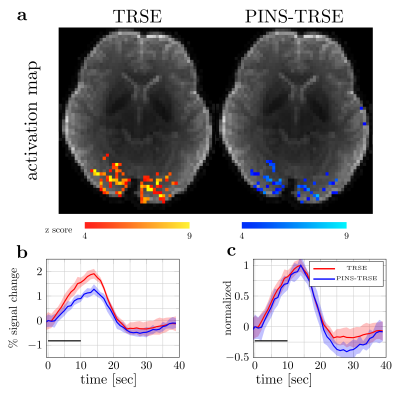

Functional MRI (fMRI) experiment: A healthy volunteer was scanned, having provided written informed consent. Functional data were acquired using TRSE and PINS-TRSE sequences. The same PINS parameters were used as in simulations. A visual stimulation was presented, consisting of a flickering checkerboard (8Hz: 10/30s ON/OFF). Each functional run lasted 8.5min. Two runs were acquired for each sequence. Slice timing and motion were corrected (SPM12)11. GLM analysis (FSL feat12) was performed to create activation maps. Voxels with a z-score above 4.0 were selected as the ROI. Signals within the ROI were averaged across runs, and the mean trial response was computed.

Results & Discussion

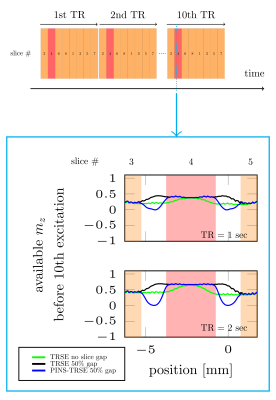

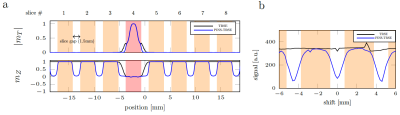

Simulation and saturation profile scan: When PINS pulse is not played, substantial longitudinal magnetizations are left in the adjacent to the excitation slice (Fig.2). However, they are highly saturated when PINS-TRSE is used, suggesting that magnetizations flowing into the target slice from the gap does not contribute to MR signal. Figure 3a shows the simulated slice profile. Within the slice of interest (slice # 4), no significant difference between TRSE and PINS-TRSE was observed. However, PINS-TRSE clearly shows the longitudinal magnetization in slice gaps is saturated. An experimentally acquired ‘saturation’ profile matched the indented saturation profile (Fig.3).Flow phantom scan: As expected, without the PINS saturation module, a bright signal is observed in the tubes with flowing water (Fig.4b). Removing the slice gaps does little to suppress inflow effects (Fig.2). Using a 1-s TR the slices, adjunct slices to the excitation slice were excited 375 and 500ms ago. Therefore, there still is ample time for fresh magnetization to flow into the imaging slice. When our PINS saturation module is used, inflow effects disappear from all slices without degrading signal intensity of the stationary spins in the slice.

FMRI experiment: The SAR as reported by the scanner console was increased from 53% (TRSE) to 57% (PINS-TRSE). Interestingly, with same z-score threshold, less activation was detected using PINS-TRSE. In addition, the percent signal change decreased when PINS pulses were played (1.90% vs 1.27% for TRSE vs PINS-TRSE (Fig.5b)), suggesting a non-negligible inflow effect. The PINS pulse may, in addition to the inflow saturation, also add more magnetization transfer effects, which might contribute to the percent signal change drop.

Conclusion

Inflow effects from slice gaps were successfully suppressed by our PINS inflow-saturation pulse. The PINS periodicity can be modulated by changing the pulse profile, therefore this strategy can be applied to arbitrary slice gaps. To fully remove inflow, it is recommended to use a slice gap in combination with our PINS saturation module, because even multi-slice sequences without gap can provide ample time for fresh magnetization to flow into the imaging slice. The inflow saturated fMRI data revealed that inflow has non-negligible contribution to the functional response. This PINS implementation allows us to further understand fMRI signal dynamics by tuning on and off the inflow effect.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by ARC Future fellowship grant FT200100329, by the NIH NIBIB (grants P41-EB03006, R01-EB019437 and R01-EB032746) and by the BRAIN Initiative (NIH NIMH grant R01-MH111419 and NINDS grant U19-NS123717). The authors acknowledge the facilities of the National Imaging Facility at the Centre for Advanced Imaging.References

1. Howseman, A. M., Grootoonk, S., Porter, D. A., Ramdeen, J., Holmes, A. P., & Turner, R. (1999). The effect of slice order and thickness on fMRI activation data using multislice echo-planar imaging. Neuroimage, 9(4), 363-376.2. Golay, X., Hendrikse, J., & Lim, T. C. (2004). Perfusion imaging using arterial spin labeling. Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 15(1), 10-27.

3. Miyazaki, M., & Lee, V. S. (2008). Nonenhanced MR angiography. Radiology, 248(1), 20-43.

4. Whittaker, J. R., Fasano, F., Venzi, M., Liebig, P., Gallichan, D., Möller, H. E., & Murphy, K. (2021). Measuring Arterial Pulsatility With Dynamic Inflow Magnitude Contrast. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15.

5. Fultz, N. E., Bonmassar, G., Setsompop, K., Stickgold, R. A., Rosen, B. R., Polimeni, J. R., & Lewis, L. D. (2019). Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science, 366(6465), 628-631.

6. Gao, J. H., & Liu, H. L. (2012). Inflow effects on functional MRI. Neuroimage, 62(2), 1035-1039.

7. Duyn, J. H., Moonen, C. T., van Yperen, G. H., de Boer, R. W., & Luyten, P. R. (1994). Inflow versus deoxyhemoglobin effects in BOLD functional MRI using gradient echoes at 1.5 T. NMR in Biomedicine, 7(1‐2), 83-88.

8. Norris, D. G., Koopmans, P. J., Boyacioğlu, R., & Barth, M. (2011). Power independent of number of slices (PINS) radiofrequency pulses for low‐power simultaneous multislice excitation. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 66(5), 1234-1240.

9. Barth, M., Breuer, F., Koopmans, P. J., Norris, D. G., & Poser, B. A. (2016). Simultaneous multislice (SMS) imaging techniques. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 75(1), 63-81.

10. Wu, C., Jin, J., Dixon, C., Maillet, D., Barth, M., & Cloos, M.. Velocity selective arterial spin labelling using parallel transmission. In Proc. of the 31st Annual Meeting of ISMRM. London, England UK.

11. Penny WD, Friston KJ, Ashburner JT, Kiebel SJ, Nichols TE, editors. Statistical parametric mapping: the analysis of functional brain images. Elsevier; 2011.5.

12. M.W. Woolrich, B.D. Ripley, J.M. Brady and S.M. Smith. Temporal Autocorrelation in Univariate Linear Modelling of FMRI Data. NeuroImage 14:6(1370-1386) 2001.6.

Figures

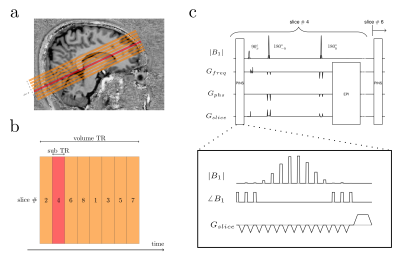

Fig1. (a) Slice positioning on visual cortex. Orange and red blocks show slice coverage. 50% slice gaps are seen in between. (b) 2D TRSE acuisition order. Usually, slices are acquired interleavedly like shown to mitigate slice cross-talk. (c) PINS-TRSE sequence. PINS pulse block is played before every excitation pulse. The PINS profile used for the simulation and phantom scan were; number of sub peaks = 14, flip angle= 90°, BW = 427.35 Hz, periodicity = 4.5 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm, pulse duration = 7ms.

Fig2. Bloch simulation results of available longitudinal magnetiations before 10th excitation. Here, slice number 4 (highloghted as red) is focused. In the 10th TR, each slice gaps was already excited more than 72 times (9TR x 8slices). Strong saturation in slice gap but not saturation in the target slcie arre seen. Simulation parameters were followings; slice thickness = 3 mm, number of slices=8, T1=1600ms, T2=75ms, and TR= 1 and 2sec respectively,

Fig3. (a) Slice profile of the target slice (highlighted as red, slice #4). (b) One slice acquisition using PINS-TRSE was performed to measure ‘saturation’ profile experimentally. When saturation and excitation slices are overlapped (shift = 0mm), there was minimum signal left, however when excitation slices do not ‘see’ the saturation (shift =±2.25mm), maximum signal was observed. The measured MRI signal was plotted as a function of the excitation pulse shift distance. Number of slice = 1, TR = 1s, TE = 75ms.

Fig4. (a) Flow phantom containing 4 tubes with flowing water. The red allows indicate the water flow direction. The flow was provided by a water tank and pump control system placed in a console room, refulated by an Arduino. The flow rate was approximately 1.5cm/sec. (b) Flow phantom images of all 8 slices. When PINS pulse is not played and there is no slice gap, each four tube shows high signal intensity, indicating inflow effect. However, when PINS pulse was played, the tubes show low signal intensity, indicating that inflow effect was suppressed.

Fig5. (a) z-score maps. Functional data were acquired with volume-TR=1s, 510 volumes, 8 slices, slice gap=1.5mm, TE=75mm, matrix size=76x76, 3mm iso voxel, covering the calcarine sulcus (Fig.1a). (b) Percent signal change. Black solid line represents ‘on’ block. (c) Normalized response. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. A faint response onset time difference is seen, however the difference is within the confidence intervals. The impact of this inflow on the temporal characteristics of the fMRI response will be further investigated in a larger group of subjects.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3844