3816

3D free-breathing renal DCE MRI with high spatial and temporal resolution using Multitasking1Radiology, Beichen Hospital, Tianjin, China, 2UIH America, Inc., Houston, TX, United States, 3School of Biomedical Engineering, ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai, China, 4Radiology, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Kidney, DSC & DCE Perfusion

A 3D, free-breathing renal DCE MRI technique is developed using MRI Multitasking. It produces motion-resolved, high spatial and temporal resolutions images, thus does not require image registration post-processing. The feasibility of this technique in renal DCE MRI is evaluated on healthy subjects.Introduction

Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI can be used to non-invasively characterize renal function by measuring renal blood flow, glomerular filtration rate and various transit times. However, its clinical adoption has been hindered by low spatial and temporal resolutions and the need for breath-hold [1,2]. MRI Multitasking is an emerging technique that can resolve multiple ‘tasks’ simultaneously using a low-rank tensor model [3,4], one benefit being accelerated reconstruction of multi-dimensional images. With free-breathing, Multitasking has been shown to produce images with high spatiotemporal resolution for multiple applications, including dynamic T1 mapping of pancreas, carotid vessel and breast, and myocardial mapping without electrocardiogram [5-8]. These abilities make Multitasking a potential technique for renal MRI. Here we seek to establish the feasibility of Multitasking, using a coronal scan strategy, as a 3D, free-breathing renal DCE solution with high spatial and temporal resolution.Methods

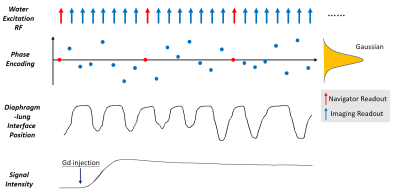

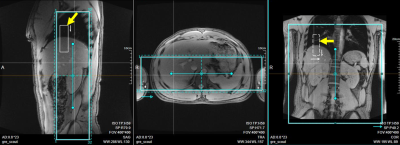

Sequence design: A 3D spoiled-GRE pulse sequence was developed featuring continuous data acquisition throughout the scan. The encodings along the slab and phase-encoding directions followed randomized Gaussian distribution, with every eighth readout being a navigator readout without encoding (Figure 1). Coronal orientation was used so that a thin slab can cover the kidneys efficiently. Water excitation was used for fat suppression. Read-out was along the head-foot direction. A cubic volume-of-interest (VOI) on the scanner console was carefully placed over the lung-diaphragm interface (Figure 2) and within the imaging volume for tracking respiratory motion.Reconstruction: Reconstruction followed similar procedures as in previous publications [5-7]. Specifically, the underlying multidimensional images are represented by a 3-way tensor $$$\bf \it A$$$ with its first dimension concatenating 3D voxel locations and other two dimensions indexing respiratory-motion and DCE time-course. Preliminary real-time reconstruction with 42 ms temporal resolution was first performed and the relative diaphragm-lung interface position was identified by an image post-processing algorithm, based on which each imaging readout was assigned to one of twelve respiratory states. Then a multi-dimensional temporal basis $$$\Phi$$$ can be determined from navigator readouts (Red circles in Figure 1) using high-order singular value decomposition. Applying the principle of partial separability, $$$A_{(1)}=U\Phi$$$ , where $$$A_{(1)}$$$ is the mode-1 matricization of $$$\bf \it A$$$ and $$$U$$$ is the spatial factors. $$$U$$$ can be recovered by solving the optimization problem:

$$\widehat{U}=argmin_{U}{\parallel d_{img} - \Omega F S U \Phi\parallel}_2^2 + R(U)$$

where $$$d_{img}$$$ is the acquired imaging readout (Blue circles in Figure 1), $$$\Omega$$$ is undersampling operator, $$$F$$$ is Fourier transform operator, $$$S$$$ is coil sensitivity operator, and $$$R$$$ is spatial total variation regularization operator. 12 respiratory motion states were used for reconstruction. Inline reconstruction was approximately 10 mins.

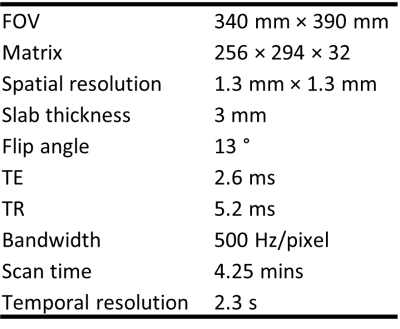

Study experiment: All data were acquired on a clinical 3T scanner (uMR790, United Imaging, Shanghai, China). Imaging parameters are summarized in Table 1. Twelve volunteers were recruited after IRB consent for kidney DCE imaging. Intravenous bolus injection of 3ml gadodiamide (Omniscan, GE Healthcare, Ireland) was performed with the flow rate of 3.0 ml/s. A temporal resolution of 2.3 sec was empirically chosen for this specific application, although the technique enables reconstruction using arbitrary temporal resolution. For kinetic modeling, images were imported to a vendor provided post-processing workstation. After manually placing ROIs in the aorta for the arterial input function, the Tofts model was employed for pixel-wise kinetic parameter fitting in the kidneys. In one subject a 1 sec temporal resolution reconstruction was also performed, to illustrate differences in contrast enhancement dynamics.

Results

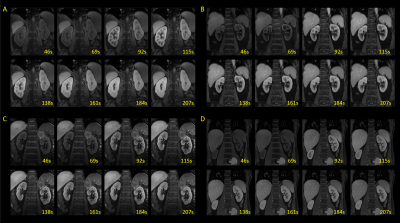

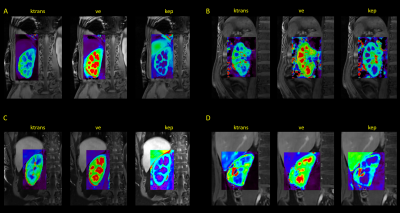

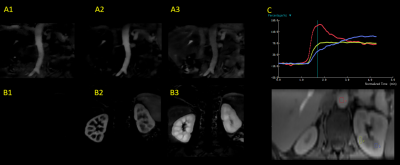

Typical DCE images are shown in Figure 3. The images demonstrate very high resolution that permits resolving fine structures in the FOV. The kidneys are automatically registered, showing distinct contrast in select time frames between cortex and medulla. Sample kinetic parameter maps are shown in Figure 4. Good and clear contrast between cortex and medulla reflects that any motion among the temporal frames was properly handled by the technique. Figure 5 shows images from one subject reconstructed with a 1 sec resolution. Subtracted images correspond to aortic, renal cortical, and renal medullary phases. Enhancement curves from different tissues exhibit unique patterns.Conclusion and discussion

A 3D, free-breathing renal DCE MRI technique with 1.3×1.3×3.0 mm3 spatial and 2.6 s temporal resolution was developed. Thanks to Multitasking’s low-rank tensor imaging strategy, this technique can produce motion-resolved, high quality dynamic images. These automatically co-registered images should eliminate the need for further post-processing, which potentially introduces errors in parameter mapping. The feasibility of kinetic modeling with this new technique was also demonstrated using Tofts model. Future studies should involve models more suitable for kidney kinetic fitting, and should focus on cross-validation this high temporal resolution MRI DCE technique with CT-based DCE in healthy and diseased populations.Acknowledgements

This work was partially facilitated by a non-exclusive license agreement between Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and United Imaging Healthcare.References

[1] Liu W, Sung K, Ruan D. Shape-based motion correction in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for quantitative assessment of renal function. Med Phys 2014;41:122302.

[2] Notohamiprodjo M, Reiser MF, Sourbron SP. Diffusion and perfusion of the kidney. Eur J Radiol. 2010;76(3):337-347.

[3] Shaw JL, Yang Q, Zhou Z, Deng Z, Nguyen C, Li D, Christodoulou AG. Free-breathing, non-ECG, continuous myocardial T1 mapping with cardiovascular magnetic resonance multitasking. Magn Reson Med. 2019 Apr;81(4):2450-2463.

[4] Christodoulou AG, Shaw JL, Nguyen C, Yang Q, Xie Y, Wang N, Li D. Magnetic resonance multitasking for motion-resolved quantitative cardiovascular imaging. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2(4):215.

[5] Wang N, Gaddam S, Wang L, et al. Six-dimensional quantitative DCE MR Multitasking of the entire abdomen: Method and application to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Magn Reson Med. 2020; 84: 928– 948.

[6] Wang N, Christodoulou AG, Xie Y, et al. Quantitative 3D dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MR imaging of carotid vessel wall by fast T1 mapping using Multitasking. Magn Reson Med. 2019; 81: 2302– 2314.

[7] Wang N, Xie Y, Fan Z, et al. Five-dimensional quantitative low-dose Multitasking dynamic contrast- enhanced MRI: Preliminary study on breast cancer. Magn Reson Med. 2021; 85: 3096– 3111.

[8] Cao T, Wang N, Kwan AC, et al. Free-breathing, non-ECG, simultaneous myocardial T1, T2, T2*, and fat-fraction mapping with motion-resolved cardiovascular MR multitasking. Magn Reson Med. 2022; 88: 1748- 1763.

Figures