3806

Assessment of Donor Kidney Storage Using a Porcine Model1Sir Peter Mansfield Imaging Centre, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, 3Big Data Institute, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Kidney, Transplantation

Here, we investigate in a porcine model how MR parameters change as donor kidneys are cold stored, by studying the effect of temperature, cold ischaemia time and compare static cold storage (SCS) with hypothermic machine perfusion (HMP).Variation in relaxometry measurements with temperature has been modelled allowing the comparison of in-vivo and ex-vivo datasets, especially important when considering T1 measurements. The effects of cold ischemia time on relaxometry measures have also been quantified allowing this confounding factor to be accounted for in larger studies of human deceased donor organs. Susceptibility Weighted Imaging observed blood products in an SCS porcine kidney.

Introduction

Deceased kidney donor organs are the most common type of organ used for transplant. Donor kidneys are flushed during retrieval to remove blood and transported in University of Wisconsin (UW) preservation solution on melting ice, a process termed static cold storage (SCS). The length of time from retrieval to transplantation is termed cold ischaemia time (CIT) and varies widely, particularly in kidneys declined for transplant but offered for research. Further, hypothermic machine perfusion (HMP), where preservation solution is continually pumped through the kidney while it is stored in an ice bath has been shown to be beneficial as a kidney preservation method over traditional SCS, but the underlying mechanisms are still not fully understood1,2. The ADMIRE (Assessing Donor kidneys and Monitoring Transplant Recipients) study is currently underway to assess the quality of human kidneys declined for transplant using ex-vivo MRI. Here, we investigate in a porcine model how MR parameters change as kidneys are cold stored, by studying the effect of temperature, cold ischaemia time and compare SCS with HMP.Methods

All kidneys were acquired from an abattoir with minimum warm ischemia time and flushed to remove blood. Kidneys were transported to the imaging centre either undergoing SCS or HMP preservation. Imaging of the kidney was performed on a Philips 3T scanner using a 32-channel head coil.Static cold storage compared to hypothermic machine perfusion

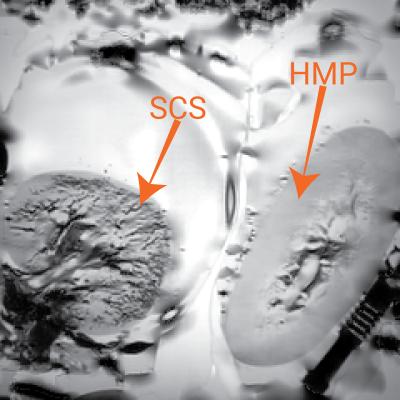

A comparison of SCS and HMP was performed to investigate the success of the flushing of blood products from the kidney. A susceptibility weighted image (SWI) (TE=10ms, echo-spacing=10ms, 4 echoes, flip-angle=55°, voxel-size=0.5x0.5x1mm3, FoV=160x160x15mm3, NSA=3) was collected due to its sensitivity to the presence of paramagnetic haemoglobin causing a signal intensity reduction.

Temperature Dependence of MR relaxometry

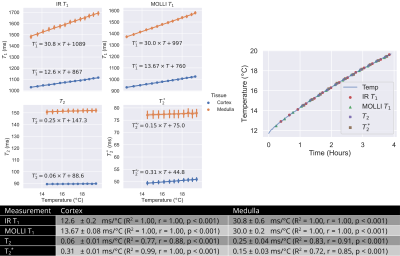

MR relaxation times vary with temperature3,4. Although kidney temperature remained relatively constant while stored on ice, temperature changes can occur during scanning (~+2.5°C over 2-hour scan session). The effect of temperature on renal T1, T2 and T2* was investigated. Kidney temperature was continually monitored while removed from SCS during scanning using a LumaSense fluoroptic thermometer5 whilst relaxometry measures of a SE-EPI T1 IR, MOLLI T1, GraSE T2 and multi-echo-GRE T2* were repeated. Each measurement block took ~15 minutes and was repeated for 4-hours as the kidney warmed. The cortex and medulla was segmented using a T2w-FSE scan and a Gaussian mixture model and the mean computed. A linear regression was fit to characterise the trend in each measure with temperature.

Cold Ischemia Time

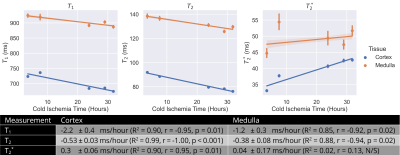

Human organs that are declined for transplant but accepted for research are transported from the donor hospital to a recipient hospital then the imaging centre, so kidneys have variable CIT at the point of imaging. To understand the impact of this, a SCS porcine kidney was scanned with variable CIT of 3.5 to 32 hours. The protocol comprised a T2w-FSE for registration of images between scan sessions, an IR T1, GraSE T2 and multi-echo GRE T2* at 2mm3 isotropic resolution, all collected in a 30-minute scan session to minimise any warming of the kidney. Mean cortex and medulla relaxometry parameters were calculated for each timepoint and a linear regression performed to characterise any trend with CIT.

Results

Figure 1 shows a SWI of two kidneys, one stored under SCS and one under HMP. Low signal intensity can be seen in the vessels of the SCS kidney indicating not all blood products were removed by the UW flush. As expected, relaxometry measures had a significant variation with temperature, Figure 2. T1 had the largest dependence at 12.6±0.2ms/°C and 30.8±0.6ms/°C in the cortex and medulla respectively using an IR sequence. T2 and T2* have a considerably lower dependence at 0.06±0.01ms/°C and 0.31±0.01ms/°C respectively for cortex, and 0.25±0.04ms/°C and 0.15±0.03ms/°C respectively for medulla. Figure 3 shows the change in T1 and T2 of the kidney with CIT was -2.0±0.4ms/hour and -0.53±0.03ms/hour respectively for the cortex and -1.2±0.3ms/hour and -0.38±0.08ms/hour respectively for the medulla. T2* increased at 0.30±0.06ms/hour in the cortex, no significant change was observed in medullary T2*.Discussion

SWI successfully identified blood products remaining in the vasculature of the SCS kidney, an effect not observed in the HMP kidney, this could be a potential cause for lower function of the organs that are SCS compared to HMP prior to transplant6,7. The temperature dependence of relaxometry measures was established. Although, the range of temperatures was higher than for cold ex-vivo samples, the linear relationship between temperature and T1 has been show to hold over temperatures of 0°C-20°C in the liver3. Extrapolating values in Figure 2 to 0°C results in similar values to those measured in Figure 3, and the regression enables comparison of ex-vivo ~0°C data with in-vivo ~37°C measures. T1 and T2 of the cortex and medulla, and T2* of the cortex showed a relatively small but significant dependence on cold ischemia time.Conclusion

SWI has observed blood products remaining in the vasculature of a SCS porcine kidney. Variation in relaxometry measurements with temperature has been modelled allowing comparison of in-vivo and ex-vivo datasets, especially T1. The effects of CIT on relaxometry measures have been quantified allowing this confounding factor to be accounted for in group studies of human deceased donor organs.Acknowledgements

This work is funded by Kidney Research UK Grant KS_RP_002_20210111.References

1. O’Callaghan JM, Morgan RD, Knight SR, Morris PJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of hypothermic machine perfusion versus static cold storage of kidney allografts on transplant outcomes. Br. J. Surg. 2013;100:991–1001 doi: 10.1002/bjs.9169.

2. Taylor MJ, Baicu SC. Current state of hypothermic machine perfusion preservation of organs: The clinical perspective. Cryobiology 2010;60:S20–S35 doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.10.006.

3. Young LAJ, Ceresa CDL, Mózes FE, et al. Noninvasive assessment of steatosis and viability of cold-stored human liver grafts by MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;86:3246–3258 doi: 10.1002/mrm.28930.

4. Kraft KA, Fatouros PP, Clarke GD, Kishore PRS. An MRI phantom material for quantitative relaxometry. Magn. Reson. Med. 1987;5:555–562 doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910050606.

5. Williams HJ, Gao Y, Ian Scott A, Gross MH, Sun MH. Use of fluoroptic thermometer temperature sensing for high-resolution temperature-controlled NMR applications. J. Magn. Reson. 1969 1988;78:338–343 doi: 10.1016/0022-2364(88)90279-X.

6. Nicholson ML, Hosgood SA, Metcalfe MS, Waller JR, Brook NR. A Comparison of Renal Preservation by Cold Storage and Machine Perfusion Using a Porcine Autotransplant Model. Transplantation 2004;78:333–337 doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000128634.03233.15.

7. Matsuoka L, Shah T, Aswad S, et al. Pulsatile Perfusion Reduces the Incidence of Delayed Graft Function in Expanded Criteria Donor Kidney Transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2006;6:1473–1478 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01323.x.

Figures