3804

Restricted Water Diffusion in the Renal Cortex is Associated with Early Developmental Factors and Elevated Urinary Cytokines in Preadolescents1Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences, Singapore, Singapore, 2Khoo Teck Puat-National University Children's Medical Institute, National University Health System, Singapore, Singapore, 3Department of Paediatrics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore, 4Department of Radiology, NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, IL, United States, 5Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore, Singapore, 6Department of Reproductive Medicine, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Singapore, Singapore, 7Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore, 8Department of Maternal Fetal Medicine, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Singapore, Singapore, 9Academic Medicine, Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School, Singapore, Singapore, 10Department of Pediatrics, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Singapore, Singapore, 11Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore, 12Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Human Potential Translational Research Programme, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore, 13MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Centre and NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, University of Southampton and University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, United Kingdom, 14Liggins Institute, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 15Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 16Folkhälsan Research Center, Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 17School of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 18School of Molecular Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia, 19Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Kidney, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Intravoxel Incoherent Motion Imaging, Renal Inflammation

Developmental factors that impair nephrogenesis can increase risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The early stages of CKD are characterized by an increased infiltration of inflammatory cells into the renal interstitium, which can restrict the molecular diffusion of water. We found that maternal gestational diabetes and preterm birth were associated with 2-fold and 4-fold higher risk of having restricted water diffusion (IVIM diffusion coefficient < 10th centile) in the renal cortex of preadolescents, respectively. Preadolescents with restricted diffusion had elevated urinary pro-inflammatory, chemotactic and pro-fibrotic cytokines, without elevations in blood markers of systemic inflammation, which was suggestive of renal inflammation.Background

The burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is high in Singapore, with the country having the 4th highest prevalence and the 7th highest incidence of kidney failures, globally1. Current approaches for primary prevention of CKD have been focused on adults and on the two major upstream risk factors for CKD, diabetes and hypertension. There is considerable evidence that the risks for CKD can originate in-utero, and that perinatal perturbations can impair nephrogenesis, which ceases by the 36th week of gestation2, 3. The resulting nephron deficit can impose a higher filtration load on the remaining nephrons. The compensatory hyperfiltration and glomerular/tubular hypertrophy of the individual nephrons to meet the higher filtration load can increase the risk for renal injury and sclerosis. Given that early CKD is asymptomatic and can have early-life origins, there is an urgent need to develop better diagnostic and prevention strategies, particularly focused on the younger population. However, this is hampered by the fact that conventional clinical kidney function markers such as estimated glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria have a high intraindividual variability and substantial irreversible kidney damage (tubulointerstitial fibrosis/glomerulosclerosis) can occur before these markers become deranged. The early stages of progressive kidney diseases, irrespective of the initial insult, are characterized by an increased infiltration of inflammatory cells into the renal interstitium4 which can restrict the molecular diffusion of water5. Maladaptive responses can result in tubular atrophy and tubulointerstitial fibrosis which can further restrict water diffusion5. We hypothesized that restricted renal cortex water diffusion, assessed by intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) imaging is sensitive to early inflammatory changes in the renal cortex in preadolescents, and evaluate its association with urinary cytokines6. We also evaluated the association of restricted water diffusion in renal cortex with early developmental factors and markers of systemic inflammation.Methods

The study population consisted of 435 preadolescents (Chinese, Indian and Malay ethnicities) from the Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) mother-offspring cohort who attended an MRI visit at the 10.5-year time-point. Imaging was performed on a 3T MRI scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens). IVIM imaging of the kidneys7 was performed using a respiratory-triggered echo-planar imaging sequence (25 coronal slices, slice-thickness = 4mm, averages=1, parallel imaging factor =2, 7 b-values: 0, 30, 70, 100, 200, 400 & 800 s/mm2). Regions of interests (ROI) were manually drawn on the renal cortex of both left and right kidneys in the lowest b-value image. Biexponential fitting of the decay in mean cortical ROI signal intensity with increasing b-values was used to extract the true molecular water diffusion parameter, D. A diffusion value less than the 10th centile was used to identify subjects with restricted water diffusion. We evaluated the association of pre-pregnancy maternal overweight/obesity, gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain (GWG), small-for gestational age and pre-term birth with offspring restricted cortical diffusion in separate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models, each adjusted for sex, ethnicity and maternal educational status. Assessment of urinary cytokines from first morning urine samples was performed via a multiplex bead assay (Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 27-plex Assay), and was available in 225 preadolescents. Cytokine concentrations were adjusted for urinary dilution by normalizing for urinary creatinine and then converted to z-scores. Between children with normal and restricted renal water diffusion, we compared the levels of urinary cytokines, body mass index (BMI) and blood markers of systemic inflammation (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and glycoprotein acetyls (GlycA)) using a t-test.Results

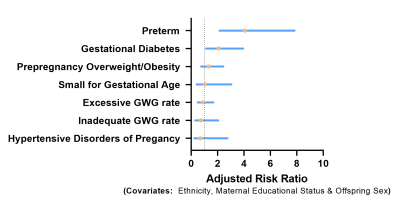

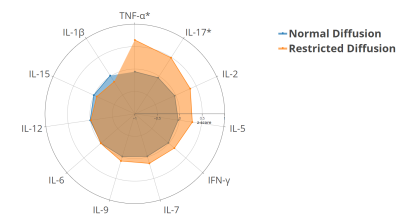

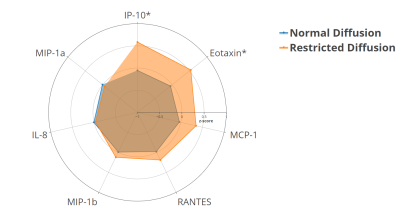

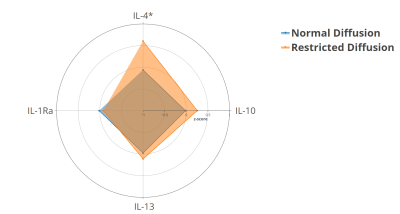

The mean±SD and 10th centile of cortical water diffusion (D) was 1.67±0.25 ×10-3mm2/s and 1.48×10-3mm2/s, respectively. Among early developmental factors assessed, we found gestational diabetes and preterm birth were associated with a 2-fold and a 4-fold higher risk of having restricted renal cortical diffusion, respectively (Fig. 1). We found that preadolescents with restricted cortical diffusion had elevations in urinary pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-17 (Fig. 2), chemotactic cytokines, IP-10 and Eotaxin (Fig.3) and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 (Fig.4), which has been associated with M2 macrophage infiltration and fibrosis in the kidney (all P<0.05). They also had significantly lower BMI, but no significant differences in blood markers of systemic inflammation (hs-CRP and GlycA) when compared to children with normal diffusion (Fig.5).Discussion & Conclusion

We found restricted renal cortex water diffusion in preadolescents to be associated with elevated urinary proinflammatory, chemotactic and pro-fibrotic cytokines. These changes were not accompanied by an elevation in clinical blood markers of systemic inflammation, which suggest that these changes may reflect renal inflammation. While increased body size and obesity are linked to an increased filtration load on the kidney, we found children with restricted cortical diffusion had a lower BMI. This suggests that the reported cortical microstructural changes in preadolescents may be related to early life factors rather than current body size. This is supported by our finding of 2-fold and 4-fold higher risk of restricted cortical diffusion in children born to mothers with gestational diabetes, and those born preterm, respectively. Both these early life factors have been associated with impaired nephrogenesis8,9. Our work highlights the utility of noninvasive MRI and urinary inflammatory markers for tracking early subclinical changes associated with developmentally programmed kidney dysfunction.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Medical Research Council, Singapore (NMRC)- Young Investigator Research Grant (OFYIRG18nov-0011) and the National University of Singapore Health System- SEED grant (NUHSRO/2020/024/T1/Seed-Aug/08). Additional funding was provided by Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences (SICS), Agency for Science Technology and Research, Singapore (A*STAR). Keith Godfrey is supported by UK Medical Research Council (UK MRC) (MC_UU_12011/4), National Institute for Health Research (NF-SI-0515-10042 & IS-BRC-1215-20004), European Union (Erasmus+ Programme ImpENSA 598488-EPP-1-2018-1-DE-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP), British Heart Foundation (RG/15/17/3174) and US National Institutes of Health’s National Institute On Aging (Award No. U24AG047867). The GUSTO cohort is supported by NMRC, Singapore [NMRC/TCR/004-NUS/2008, NMRC/TCR/012-NUHS/2014, OFLCG19May-0033]. The funding agencies had no role in the study’s design, conduct and reporting.References

1. Singapore Renal Registry Annual Report 2020.

2. Moritz KM, Singh RR, Probyn ME, Denton KM. Developmental programming of a reduced nephron endowment: more than just a baby's birth weight. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2009; 296: F1-F9.

3. Boubred F, Saint-Faust M, Buffat C, Ligi I, Grandvuillemin I, Simeoni U. Developmental origins of chronic renal disease: an integrative hypothesis. International journal of nephrology 2013; 2013.

4. Farris AB, Colvin RB. Renal interstitial fibrosis: mechanisms and evaluation in: current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension 2012; 21: 289.

5. Sułkowska K, Palczewski P, Furmańczyk-Zawiska A, et al. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of renal function and parenchymal changes in chronic kidney disease: a preliminary study. Annals of Transplantation 2020; 25: e920232-1.

6. Wong W, Singh AK. Urinary cytokines: clinically useful markers of chronic renal disease progression? Current Opinion in nephrology and hypertension 2001; 10: 807-11.

7. Ljimani A, Caroli A, Laustsen C, et al. Consensus-based technical recommendations for clinical translation of renal diffusion-weighted MRI. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 2020; 33: 177-95.

8. Amri K, Freund N, Van Huyen JD, Merlet-Bénichou C, Lelievre-Pégorier M. Altered nephrogenesis due to maternal diabetes is associated with increased expression of IGF-II/mannose-6-phosphate receptor in the fetal kidney. Diabetes 2001; 50: 1069-75.

9. Black MJ, Sutherland MR, Gubhaju L, Kent AL, Dahlstrom JE, Moore L. When birth comes early: effects on nephrogenesis. Nephrology 2013; 18: 180-2.

Figures