3787

DIMOND:DIffusion Model OptimizatioN with Deep learning1Department of biomedical engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 3Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 4Department of Engineering Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

The accurate estimation of diffusion model parameter values using non-linear optimization is time-consuming. Supervised learning methods using neural networks (NNs) are faster and more accurate but require external ground-truth data for training. A unified and self-supervised learning-based diffusion model estimation method DIMOND is proposed. DIMOND maps diffusion data to model parameter values using NNs, synthesizes the input data from the predictions using the forward model, and minimizes the difference between the raw and synthetic data. DIMOND outperforms conventional ordinary least square regression (OLS) and has a high potential to improve and accelerate data fitting for more complicated diffusion models.Introduction

Fitting the microstructural model to diffusion MRI data often requires non-linear optimization, which is computationally expensive and prohibitively time consuming especially for large-scale studies. Non-linear optimization results also heavily rely on the implementation, such as the optimization algorithm and initialization strategy, which is therefore often specifically designed for each diffusion model, slowing down the development, deployment, and distribution of new models.Deep learning techniques, particularly neural networks (NNs), have demonstrated superior performance in improving and accelerating the estimation of model parameters1,2. NNs can also dramatically reduce the required q-space samples, thereby shortening the acquisition time to increase the feasibility of microstructure imaging.

Nevertheless, current deep learning methods are mostly supervised. NNs are trained to map diffusion data to ground-truth parameter values, which induces several challenges. First, training targets are often obtained from substantially longer scans of numerous subjects, which are difficult to acquire. Second, NNs trained on one dataset might be not optimal for another diffusion dataset acquired with different hardware systems, spatial resolutions, b-values, diffusion-encoding directions and so on.

We propose a unified and self-supervised deep learning-based method “DIMOND” (DIffusion Model OptimizatioN with Deep learning) to address these challenges. DIMOND’s NN maps input diffusion data to model parameter values and is trained to minimize the difference between the input data and synthetic data generated from the NN predictions via the forward model. This approach has been successfully used for 1D signal modeling in IVIM3,4 and relaxometry5-7. We demonstrate the efficacy of DIMOND for 3D signals in the diffusion tensor modeling, evaluate the effects of convolution and explore various strategies to shorten the training time.

Methods

HCP data. Pre-processed diffusion data (18×b=0, 90×b=1000 s/mm2) at 1.25×1.25×1.25 mm3 resolution of 10 subjects from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) WU-Minn-Ox Consortium8,9 were used. For each subject, one b=0 and the first 15 DWI volumes along uniform directions were used for evaluating and comparing ordinary least square regression (OLS) implemented in the “dtifit” function of FSL10 and DIMOND for fitting the diffusion tensor model. Brain tissue masks derived from T1-weighted data using FreeSurfer11,12 were re-sampled to the diffusion image space.DIMOND framework. DIMOND employs a NN to map input diffusion data to unknown parameters of a diffusion model (e.g., one b=0 image and six component maps for the diffusion tensor model), which are then used to synthesize the input data via the forward model (e.g., tensor model: S0=e-BAD where S0, B, A, D are the b=0 image intensity, a diagonal matrix of b-values, the diffusion tensor transformation matrix, and six tensor components) (Fig.1). DIMOND’s NN is optimized using gradient descent by minimizing the difference between the raw and synthesized image intensities within the brain tissue where the forward model is valid.

DIMOND deployment. DIMOND’s NN was implemented using Pytorch13 and trained using Adam optimizers14 with L2 loss on 64×64×64 image blocks (12 blocks per subject 0.1s training time per block) in three ways:

(1) initialized with parameter values of another NN pre-trained on all 10 subjects and fine-tuned on each subject (baseline);

(2) initialized with parameter values of another NN pre-trained on one subject and fine-tuned on each subject;

(3) initialized with random parameter values and trained on each subject, i.e., self-supervised, subject-specific training.

Evaluation. Ground-truth tensors were fitted with all available data using OLS. Ground-truth DWIs were synthesized from ground-truth tensors. The structural similarity index (SSIM) and mean absolute error (MAE) were used to quantify the similarity between image results and ground truth. The MAEs of DTI metrics within the brain tissue comparing to ground-truth values were computed.

Results

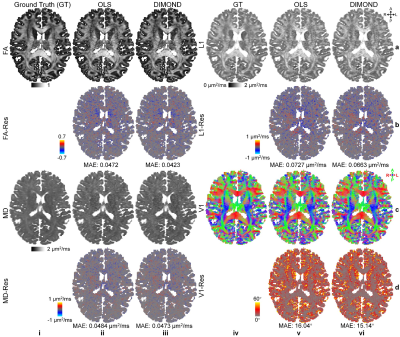

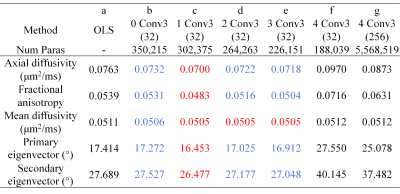

DIMOND generated cleaner tensor component maps (Fig.2a,b), b=0 image (Fig.2c), and DWI (Fig2.d) and maps of DTI metrics (Fig.3) than those from OLS while maintained the same level of sharpness and did not introduce structural bias compared to ground truth. Quantitatively, DIMOND-generated images were more similar to ground truth than raw images (SSIM: 0.9649 vs. 0.9647 for b=0 image, 0.9630 vs. 0.9073 for DWI shown in Fig.2). DIMOND-generated DTI metrics were more accurate than OLS results (Fig.4a vs. Fig.4c).Incorporating information of neighboring voxels improved DIMOND’s accuracy. DIMOND using NN with one 3×3×3 convolution layer (i.e., 3×3×3 receptive field) achieved lowest MAEs of DTI metrics (Fig.4b). Using more distant voxels (i.e., 2 to 4 3×3×3 convolution layers corresponding to 5×5×5 to 9×9×9 receptive field) hampered DIMOND’s performance (Fig.4d-f), which is not a result of the reduced number of model parameters (Fig.4c vs. Fig.4g).

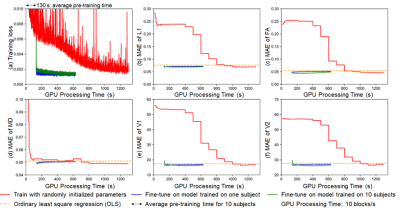

DIMOND’s MAEs of DTI metrics by directly applying the NN trained on one subject to another subject were lower than those from OLS (Fig.5b-f, orange). The high generalization rendered it feasible to fine-tune the NN pre-trained on one subject (Fig5, blue) or ten subjects (Fig5, green) to shorten the training from randomly initialized NN parameter values (Fig5, red). The training time was reduced to half, with slightly increased MAEs of DTI metrics.

Discussion and Conclusion

DIMOND is proposed to accelerate, improve and unify diffusion model fitting without the requirement for external ground-truth data. DIMOND’s NN is highly generalizable. Fine-tuning NN parameters on the data of each subject further improves the estimation accuracy. Future work will extend DIMOND to more complicated models like NODDI.Acknowledgements

The diffusion data were provided by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn-Ox Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; U54-MH091657) funded by the 16 NIH Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research; and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University.

References

1. de Almeida Martins JP, Nilsson M, Lampinen B, et al. Neural networks for parameter estimation in microstructural MRI: Application to a diffusion-relaxation model of white matter. NeuroImage. 2021;244:118601.

2. Golkov V, Dosovitskiy A, Sperl JI, et al. q-Space deep learning: twelve-fold shorter and model-free diffusion MRI scans. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2016;35(5):1344-1351.

3. Barbieri S, Gurney‐Champion OJ, Klaassen R, Thoeny HC. Deep learning how to fit an intravoxel incoherent motion model to diffusion‐weighted MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2020;83(1):312-321.

4. Vasylechko SD, Warfield SK, Afacan O, Kurugol S. Self‐supervised IVIM DWI parameter estimation with a physics based forward model. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2022;87(2):904-914.

5. Liu F, Kijowski R, El Fakhri G, Feng L. Magnetic resonance parameter mapping using model‐guided self‐supervised deep learning. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2021;85(6):3211-3226.

6. Chan K-S, Kim TH, Bilgic B, Marques JP. Semi-supervised learning for fast multi-compartment relaxometry myelin water imaging (MCR-MWI). Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM). 2022;

7. Kang B, Kim B, Schär M, Park H, Heo HY. Unsupervised learning for magnetization transfer contrast MR fingerprinting: Application to CEST and nuclear Overhauser enhancement imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2021;85(4):2040-2054.

8. Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage. 2013;80:105-124.

9. Glasser MF, Smith SM, Marcus DS, et al. The human connectome project's neuroimaging approach. Nature Neuroscience. 2016;19(9):1175-1187.

10. Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, et al. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage. 2009;45(1):S173-S186.

11. Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis: II: inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. NeuroImage. 1999;9(2):195-207.

12. Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis: I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage. 1999;9(2):179-194.

13. Paszke A, Gross S, Massa F, et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2019;32

14. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:14126980. 2014;

Figures