3773

Age Related Changes of Organs and Muscles Using a Deep Learning Based Whole Body Segmentation Technique Applied to a Healthy Adult Population

Ahmed Gouda1, Saqib Basar1, Yosef Chodakiewitz2, Rajpaul Attariwala1, Sean London2, and Sam Hashemi1

1Voxelwise Imaging Technology Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2Prenuvo, Vancouver, BC, Canada

1Voxelwise Imaging Technology Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2Prenuvo, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Aging, Volumetric Analysis, Organs, Visceral Fat, Skeletal Muscles

One of the vital indicators of normal functioning physiology and anatomy, is the volume and size of body organs and muscles. Overtime due to aging and chronic illnesses, the volume of organs and muscles decreases, and quantifying this reduction would help us in predicting the rate of decline, and making efforts to improve this rate. Artificial intelligence 3D segmentation techniques allow us to measure the average age-related volume loss over a large population. They provide statistical norms which help radiologists to identify abnormal volume changes, and establish a normal age related rate of volumetric decline.INTRODUCTION:

The process of aging is complex and is associated with a loss of tissue mass and diminished function of vital organs and muscles. In recent decades, medical imaging modalities such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computer Tomography (CT) have become a noninvasive technique of choice to measure volumetric and morphometric changes of the human anatomical structures. This gives us a picture of the current state of physiology and helps us to observe trends with aging. Subsequently radiologists will be able to monitor age-related deterioration in organs and musculoskeletal structures over longitudinal examinations. This will help identify key features of many chronic disorders, thereby creating a baseline for radiomics. Manual annotation across 3D volumes of different anatomical structures is a tedious and time-consuming task. To alleviate this issue, recent fully automated medical imaging segmentation approaches using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)1,2 have become an essential tool for anatomical measurements of the human body. In this research, we propose a fully automated whole-body segmentation model for different anatomical structures, and we carry out a population based study to measure the change in the volumes of vital organs, skeletal muscles and visceral fat per decade for our patient population.METHODS:

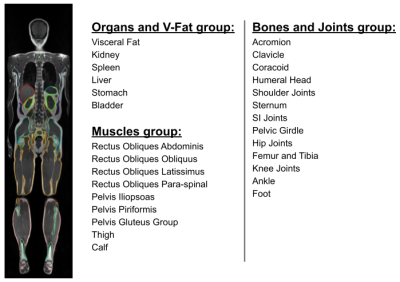

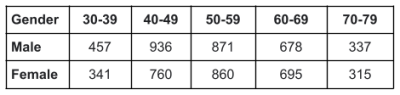

We segment 28 different anatomical classes of abdominal organs, visceral fat and skeletal muscles, bones and joints using a T1 whole-body weighted MRI acquisition, as shown in Figure 1. Two different datasets were used for segmentation and the population study. The segmentation dataset consists of 102 scans, and divided into 80 for training, 20 for validation, and 12 scans for testing. The ground-truth masks of the anatomical structures were manually annotated by radiologists. nnU-Net3,4 has been used as a fully supervised segmentation architecture for training and inferring different segmentation classes.The dataset for the population study consists of 6250 scans and the demographic distribution of the age and gender is listed in Table 1. The volumes for each anatomical structure was computed in milliliters (mL) by multiplying the number of the predicted voxels in the segmentation mask by the 3D MRI voxel space. We compute the volumetric change for some of the segmented anatomical structures, such as, visceral fat, abdominal organs (liver, kidneys, spleen), and the total muscles volume (TMV) by adding the volumes of the muscles group.

RESULTS:

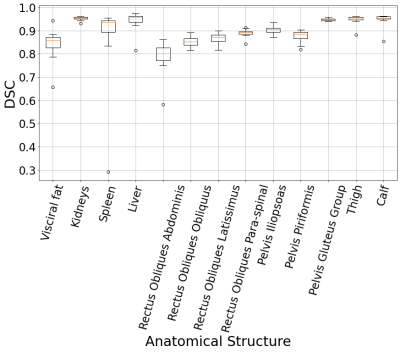

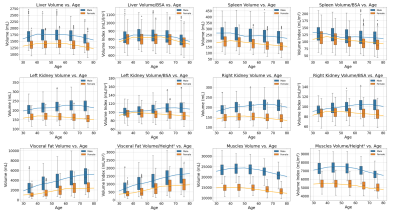

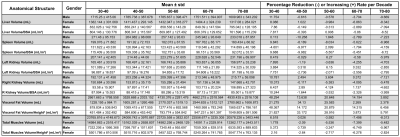

The segmentation dice scores (DSC) for the desired anatomical structures over the testing set are illustrated in box-plots in Figure 2. We report the aforementioned volumes as actual and normalized volumes for different organs with respect to gender independently. The volumes of the abdominal organs were normalized by the DuBois body surface area (BSA)5,6, while the visceral fat and the TMV were normalized by the squared value of the patient’s height. The samples were combined for each year using a sliding window (width=3), and the outliers outside the 5% to 95% percentile range were removed. Then, the data was resampled per age into the median number of years per decade chunk, and a linear regression model was fit in each decade, as demonstrated in Figure 3. From the regression lines, we computed the percentage increase (+) or reduction (-) rate per each decade by dividing the slope by the average number of samples across the decade, as shown in Table 2.DISCUSSION:

Within the same population, males tend to have bigger skeletal muscles and abdominal organs compared to females for the both actual and normalized volumes. In addition, the onset of volumetric decline varies for each organ. The experimental results show that the liver volume starts to decrease between the age decade 50-60, while the spleen starts in the age decade 30-40. The volume of the left and right kidneys is expected to start decreasing in an earlier age decade for females (40-50) compared to males (70-80). Moreover, the graphs show that aging is associated with increased accumulation of visceral fat volume. The TMV graphs indicate that it is possible to gain muscles within the decade 30 to 40, while the sarcopenia effect starts to appear in the following decades.CONCLUSION:

Emerging deep learning based segmentation systems in the medical imaging analysis domain has made great contributions for volumetric analysis of different anatomical structures over large datasets. Consequently, radiologists can utilize population wide volumetric changing trends to determine healthy aging rates for patients. This allows physicians to potentially reduce or revert adverse changes using precise personalized medicine.Future studies would include more samples to further expand the age ranges studied. Further fat volume quantification would include additional regions not specifically segmented in the present study, such as perimuscular and subcutaneous fat. Additionally, a deeper level of analysis would include tissue composition metrics, in addition to volumes, such muscle fat-fraction. The same segmentation and volume quantification principles can be applied to establishing age-based norms for arthropathies (i.e. via joint space quantifications) and age-related changes in bone marrow distribution patterns. Future studies may also explore biochemical and functional changes in association with these types of image-based volume changes, possibly supporting the use of these radiomic features as predictive correlates for such other relevant physiologic markers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the MRI Technologists, Patient Care, and Back-end teams at Prenuvo for their contributions in data acquisition.References

- Çiçek, Ö., Abdulkadir, A., Lienkamp, S. S., Brox, T., & Ronneberger, O. (2016). 3D U-Net: learning dense volumetric segmentation from sparse annotation. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 424–432.

- Bengio, Y., Courville, A., & Vincent, P. (2013). Representation learning: A review and new perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 35(8), 1798–1828.

- Fabian Isensee, Jens Petersen, Andre Klein, David Zimmerer, Paul F Jaeger, Simon Kohl, Jakob Wasserthal, Gregor Koehler, Tobias Norajitra, Sebastian Wirkert, et al. nnu-net: Self-adapting framework for u-net-based medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.10486, 2018.

- Fabian Isensee, Paul F Jaeger, Simon AA Kohl, Jens Petersen, and Klaus H Maier-Hein. nnu-net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nature methods, 18(2):203–211, 2021.

- Urata, K., Kawasaki, S., Matsunami, H., Hashikura, Y., Ikegami, T., Ishizone, S., Momose, Y., Komiyama, A., & Makuuchi, M. (1995). Calculation of child and adult standard liver volume for liver transplantation. Hepatology, 21(5), 1317–1321.

- Gehan, E. A., & George, S. L. (1970). Estimation of human body surface area from height and weight 12. Cancer Chemother. Rep, 54, 225–235.

Figures

Figure 1: Visual illustration of the segmented organ and muscle volumes, and the relevant segmentation labels.

Table 1: Number of samples per decade of the population dataset for male and female.

Figure 2: Segmentation DSC results of the desired anatomical structures over the testing set.

Figure 3: Box-plots and linear regression analysis of the anatomical structures volume change per decade for male and female.

Table 2: Statistical analysis of the actual and normalized volumes and the expected increase (+) or reduction (-) volume rate per decade.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3773