3772

Assessing the Impact of Upstream Reconstruction Models on Downstream Image Analysis: A Workflow-Centric Evaluation1Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Department of Neuroscience, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States, 3Department of Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 4Department of Computer Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 5Department of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Image Reconstruction, Segmentation, Classification

Deep learning (DL) techniques have shown promise for both reconstruction and image analysis stages of MRI workflows. However, traditional benchmarking methods evaluate each stage separately. As a result, the impact of reconstruction on downstream image analysis tasks and biomarker quantification remains unknown. In this study, we explore how changing aspects of upstream reconstruction affects the downstream analysis. We find that insights from evaluating reconstruction models as a component of a broader end-to-end workflow do not correlate with conventional, task-specific image quality metrics. We use these findings to motivate the discussion of evaluating DL methods at the workflow level.Introduction

Deep learning (DL) has demonstrated faster and automated processing at both upstream (image reconstruction) and downstream (image analysis) stages of the MRI workflow. DL methods for accelerated MRI reconstruction have enabled improved image quality at larger acceleration factors with faster reconstruction durations compared to classical methods1-4. Additionally, DL techniques for segmentation and classification have simplified assessing regions of interest and detecting pathology with a performance comparable to experts5-9.Traditionally, MRI reconstruction and analysis have been viewed as separate components of the MRI workflow. Thus, these tasks have been evaluated separately, making it impossible to quantify the downstream impact of reconstruction on image analysis tasks. The lack of clarity on how changes in different components affect the quality of the end-to-end MRI workflow has limited prospective clinical deployment10.

In this study, we explore the impact of upstream accelerated MRI reconstruction on downstream image analysis tasks and biomarker quantification accuracy. We demonstrate that metrics from end-to-end workflow-centric evaluation can be discordant with standard image quality metrics used to quantify reconstruction performance. We use this analysis to motivate characterizing performance at the full workflow level rather than for individual tasks.

Methods

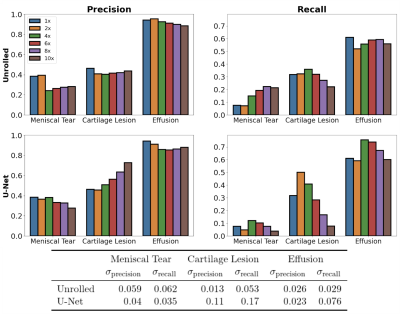

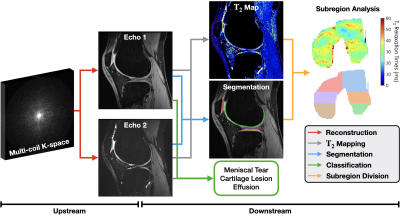

End-to-end quantitative knee MRI workflow: We use the publicly available Stanford Knee MRI Multi-Task Evaluation dataset (SKM-TEA) dataset11, consisting of 155 subjects scanned on GE MR750 scanners. We consider a quantitative accelerated knee MRI workflow for extracting cartilage T2 biomarkers, which are strong indicators for knee health12-15, and classifying knee pathology (Fig.1). In this workflow, quantitative double echo steady state (qDESS) scans are first reconstructed using a chosen reconstruction process, followed by estimation of pixelwise quantitative T2 parameter maps16. A DL segmentation model segments articular (femoral, tibial, and patellar) cartilage and meniscal tissues from the reconstructed scan. Tissue segmentations are automatically divided into sub-regions to get localized T2 estimates17,18. A DL classification model also detects cartilage lesions, meniscal tears, and joint effusion in sagittal slices of the reconstructed echoes.Reconstruction methods: We compared four reconstruction processes: 1) vendor-specific reconstruction and post-processing (i.e. DICOM reconstructions), 2) SENSE19 reconstruction of fully-sampled scans (FS-SENSE), and 3) proximal-gradient-descent unrolled20 and 4) U-Net21 DL reconstructions of accelerated scans. Both DL reconstruction models were trained to reconstruct images at 6x acceleration using the raw k-space data in the SKM-TEA dataset. At inference, DL models reconstructed scans at 2x, 4x, 6x, 8x, and 10x acceleration.

Image analysis tasks: To explore the effects of changing reconstruction techniques on downstream models, we trained two image analysis models for image segmentation and classification on 2D DICOM sagittal slices from the SKM-TEA dataset. The classification model employed a ResNet-10122 architecture where each slice was classified separately and metrics were aggregated over all considered slices. The tissue segmentation model employed a V-Net23 architecture to segment tissues. Segmentation metrics were computed on the full 3D scan.

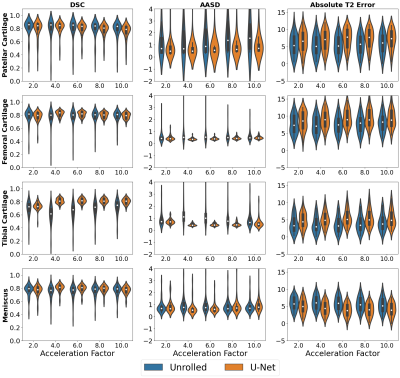

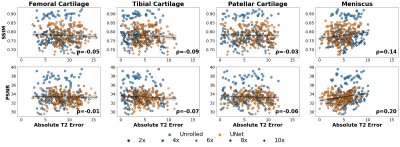

Experiments: We evaluate the impact of changes in reconstruction quality from DICOM preprocessing (DICOM vs FS-SENSE) and changes in acceleration factor 1) on conventional image analysis metrics (classification- precision, recall; segmentation- Dice, average symmetric surface distance (ASSD)) and 2) on quantifying clinically-relevant T2 estimates. Pearson’s coefficient (⍴) was used to quantify correlation between reconstruction metrics (structural similarity (SSIM) and peak-signal-to-noise (pSNR) ratio) and T2 error. All metrics are computed on the pre-defined SKM-TEA test split of 36 subjects.

Results

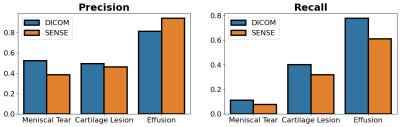

The downstream classification models consistently performed worse among FS-SENSE reconstructions than among DICOM images (Fig.2). Additionally, DL reconstructions at different acceleration factors resulted in changes in classification performance, but performance was more consistent for unrolled reconstructions than U-Net reconstructions (Fig.3).In contrast, changes in the acceleration factor demonstrated minimal performance variations for Dice, ASSD, and T2 error among segmentation models (Fig.4). Segmentations of unrolled reconstructed images had consistently more variable distributions with large outliers compared to U-Net reconstructed scans. Additionally, structural similarity (SSIM) and peak-signal-to-noise ratio (pSNR) were poorly correlated with T2 error for all tissues (⍴<0.2, Fig.5). Highest correlations were observed for the meniscus (SSIM-⍴=0.14, pSNR-⍴=0.2).

Discussion

The variable performance of the downstream models resulting from changes in upstream reconstruction methods may imply the presence of data distribution shifts is substantial enough to alter the performance of the downstream analysis models. Even small changes such as the substitution of DICOM images with SENSE-reconstructed images resulted in noticeable performance changes. In both the classification and segmentation experiments, the underlying DL reconstruction model introduced inconsistency in performance metrics, while the acceleration parameter changes primarily impacted the classification workflows. This may indicate that classification of cartilage and medical pathology requires fine-grained details that may not be recovered at higher acceleration rates. Additionally, the poor correlation between the traditional IQA metrics and end model output performance further supports the presence of a disconnect between the objectives of optimization for reconstruction and clinically-relevant analysis tasks.Conclusion

We demonstrate a new paradigm for evaluating reconstruction methods with a focus on the end-to-end MRI workflows, which accounts for changes to any component of an MRI pipeline in the context of its resulting effects on the overall clinical utility.Acknowledgements

Research support provided by NIH R01 AR077604, NIH R01 EB002524, NIH K24 AR062068, NSF-GRFP 1656518, DOD-NDSEG ARO, Precision Health and Integrated Diagnostics Seed Grant from Stanford University, Stanford Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Imaging GCP grant, Stanford Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence GCP grant, GE Healthcare, and Philips.References

[1] Hammernik, K., Klatzer, T., Kobler, E., Recht, M. P., Sodickson, D. K., Pock, T., & Knoll, F. (2018). Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated MRI data. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 79(6), 3055-3071.

[2] Sandino, C. M., Lai, P., Vasanawala, S. S., & Cheng, J. Y. (2021). Accelerating cardiac cine MRI using a deep learning based ESPIRiT reconstruction. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 85(1), 152-167.

[3] Wang, S., Su, Z., Ying, L., Peng, X., Zhu, S., Liang, F., ... & Liang, D. (2016, April). Accelerating magnetic resonance imaging via deep learning. In 2016 IEEE 13th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI) (pp. 514-517). IEEE.

[4] Knoll, F., Murrell, T., Sriram, A., Yakubova, N., Zbontar, J., Rabbat, M., ... & Recht, M. P. (2020). Advancing machine learning for MR image reconstruction with an open competition: Overview of the 2019 fastMRI challenge. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 84(6), 3054-3070.

[5] Bien, N., Rajpurkar, P., Ball, R. L., Irvin, J., Park, A., Jones, E., ... & Lungren, M. P. (2018). Deep-learning-assisted diagnosis for knee magnetic resonance imaging: development and retrospective validation of MRNet. PLoS medicine, 15(11), e1002699.

[6] Desai, A. D., Caliva, F., Iriondo, C., Mortazi, A., Jambawalikar, S., Bagci, U., ... & IWOAI Segmentation Challenge Writing Group. (2021). The international workshop on osteoarthritis imaging knee MRI segmentation challenge: a multi-institute evaluation and analysis framework on a standardized dataset. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, 3(3), e200078.

[7] Desai, A. D., Gold, G. E., Hargreaves, B. A., & Chaudhari, A. S. (2019). Technical considerations for semantic segmentation in MRI using convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.01977.

[8] Bakas, S., Reyes, M., Jakab, A., Bauer, S., Rempfler, M., Crimi, A., ... & Jambawalikar, S. R. (2018). Identifying the best machine learning algorithms for brain tumor segmentation, progression assessment, and overall survival prediction in the BRATS challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.02629.

[9] Norman, B., Pedoia, V., & Majumdar, S. (2018). Use of 2D U-Net convolutional neural networks for automated cartilage and meniscus segmentation of knee MR imaging data to determine relaxometry and morphometry. Radiology, 288(1), 177.

[10] Chaudhari, A. S., Sandino, C. M., Cole, E. K., Larson, D. B., Gold, G. E., Vasanawala, S. S., ... & Langlotz, C. P. (2021). Prospective deployment of deep learning in MRI: a framework for important considerations, challenges, and recommendations for best practices. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 54(2), 357-371.

[11] Desai, A. D., Schmidt, A. M., Rubin, E. B., Sandino, C. M., Black, M. S., Mazzoli, V., ... & Chaudhari, A. S. (2022). Skm-tea: A dataset for accelerated mri reconstruction with dense image labels for quantitative clinical evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.06823.

[12] Chaudhari, A. S., Kogan, F., Pedoia, V., Majumdar, S., Gold, G. E., & Hargreaves, B. A. (2020). Rapid knee MRI acquisition and analysis techniques for imaging osteoarthritis. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 52(5), 1321-1339.

[13] Dunn, T. C., Lu, Y., Jin, H., Ries, M. D., & Majumdar, S. (2004). T2 relaxation time of cartilage at MR imaging: comparison with severity of knee osteoarthritis. Radiology, 232(2), 592.

[14] Mamisch, T. C., Trattnig, S., Quirbach, S., Marlovits, S., White, L. M., & Welsch, G. H. (2010). Quantitative T2 mapping of knee cartilage: differentiation of healthy control cartilage and cartilage repair tissue in the knee with unloading—initial results. Radiology, 254(3), 818-826.

[15] Chaudhari, A. S., Black, M. S., Eijgenraam, S., Wirth, W., Maschek, S., Sveinsson, B., ... & Hargreaves, B. A. (2018). Five-minute knee MRI for simultaneous morphometry and T2 relaxometry of cartilage and meniscus and for semiquantitative radiological assessment using double-echo in steady‐state at 3T. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 47(5), 1328-1341.

[16] Sveinsson, B., Chaudhari, A. S., Gold, G. E., & Hargreaves, B. A. (2017). A simple analytic method for estimating T2 in the knee from DESS. Magnetic resonance imaging, 38, 63-70.

[17] Crowder, H. A., Mazzoli, V., Black, M. S., Watkins, L. E., Kogan, F., Hargreaves, B. A., ... & Gold, G. E. (2021). Characterizing the transient response of knee cartilage to running: decreases in cartilage T2 of female recreational runners. Journal of Orthopaedic Research®, 39(11), 2340-2352.

[18] Desai, A. D., Barbieri, M., Mazzoli, V., Rubin, E., Black, M. S., Watkins, L. E., ... & Chaudhari, A. S. (2019, May). DOSMA: A deep-learning, open-source framework for musculoskeletal MRI analysis. In Proc 27th Annual Meeting ISMRM, Montreal (p. 1135).

[19] Pruessmann, K. P., Weiger, M., Scheidegger, M. B., & Boesiger, P. (1999). SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 42(5), 952-962.

[20] Sandino, C. M., Cheng, J. Y., Chen, F., Mardani, M., Pauly, J. M., & Vasanawala, S. S. (2020). Compressed sensing: From research to clinical practice with deep neural networks: Shortening scan times for magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE signal processing magazine, 37(1), 117-127.

[21] Falk, T., Mai, D., Bensch, R., Çiçek, Ö., Abdulkadir, A., Marrakchi, Y., ... & Ronneberger, O. (2019). U-Net: deep learning for cell counting, detection, and morphometry. Nature methods, 16(1), 67-70.

[22] He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2016, October). Identity mappings in deep residual networks. In European conference on computer vision (pp. 630-645). Springer, Cham.

[23] Milletari, F., Navab, N., & Ahmadi, S. A. (2016, October). V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In 2016 fourth international conference on 3D vision (3DV) (pp. 565-571). IEEE.

Figures

Fig.1: Overview of a quantitative knee MRI workflow for T2 estimation and pathology classification with quantitative double echo steady state (qDESS) scans. Multi-coil k-space for both echos are first reconstructed (red). Reconstructions are used to estimate pixelwise T2 maps (gray), segment tissues (blue), and classify pathology (green). T2 maps and segmentations are combined regional T2 estimates (orange). Changes in reconstruction processes can have a considerable impact on downstream classification, segmentation, and T2 performance.

Fig.2: The effect of DICOM vs fully sampled SENSE reconstruction methods on the performance of the DICOM-trained classification model. Both DICOM and SENSE reconstruction methods use fully-sampled k-space. However, classification performance is worse on SENSE-based reconstructions. This may suggest vendor-specific DICOM postprocessing can cause data distribution shifts relative to standard SENSE-based reconstruction.