3759

Automatic brain extraction on multi-contrast dogs and cats MRI images1HawkCell, Marcy-l'Étoile, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Segmentation, Animals

Brain extraction in an MRI image is the first pre-processing step of a neuroimaging quantification pipeline. Once the brain is extracted, further post-processing becomes faster, more specific, and easier to implement and interpret. Existing brain extraction tools are mostly adapted to work on the human anatomy, or on specific animal species. This gives poor results when applied to animal brain images. We developed an atlas-based Veterinary Images Brain Extraction (VIBE) algorithm that is fully automatized and was successfully tested on different cats and dogs breeds, 3D and 2D MRI images, different contrasts (T1-weighted, T2-weighted and T2 FLAIR) and acquisition planes.Introduction

Brain extraction algorithms aim to isolate the brain parenchyma from its surrounding tissues. It is a fundamental preliminary task for every quantitative neuroimaging study, but unfortunately there are very few solutions that have been developed for the veterinary domain1,2. Most of the existing automatic tools, such as the Brain Extraction Tool (BET)3 or 3dSkullStrip (3DSS), part of the AFNI suite4, are designed for human MRI, thus performing poorly when applied to veterinary images. In addition, animal skulls have a larger amount of non-brain tissues, making the brain harder to isolate from its surrounding structures. To address this problem, we developed VIBE (Veterinary Images Brain Extraction), a robust atlas-based automatic brain extraction tool adapted to animals. We successfully tested it on cats and dogs of different breeds and cranial conformations. VIBE has proven to be robust and automatic on multiple MR sequences (3D T1, T2 FLAIR, T2 FRFSE) and all the anatomical planes (sagittal, dorsal and transverse).Methods

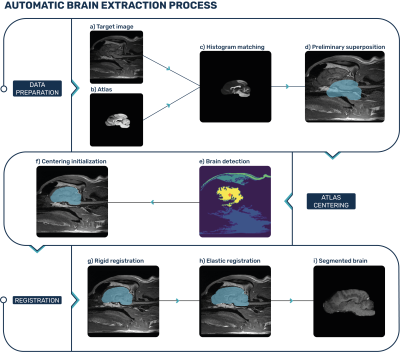

The VIBE algorithm uses an animal brain atlas to perform a fully automatic brain extraction on a head MRI scan. A first data preparation and centering step is followed by a two-stage registration process to perform the segmentation (Fig. 1).For the canine population, we used the publicly available T1-weighted canine atlas published by P. J. Johnson et al.5 because of its high resolution and the presence of mixed-breed subjects, making it more prone to adapt to a variety of canine breeds. For the feline population, a T1-weighted atlas of the same author was chosen6.

The first step of the algorithm is the resampling of the atlas. By matching the target image’s physical position and direction, the registration is made possible. A histogram matching of the atlas to the target is then performed for optimal intensity comparison.

The second step is to align the center of the atlas with the center of the brain in the target image, to ease the registration process. This is done by segmenting the target image into regions using the Felzenszwalb algorithm, then translating the center of the atlas to the center of the region identified as the brain.

Once the centers of both brains are aligned, we perform a rigid registration with six degrees of freedom, corresponding to 3D translations and rotations, to precisely superpose the atlas over the brain of the subject.

The last step in our pipeline is an elastic registration. A free-form B-spline deformation will stretch the atlas as needed to perfectly match the atlas to the subject’s brain.

All the images were acquired with a 1.5T MRI system. For each subject, a 3D T1-weighted brain volume sequence, a T2-weighted Fast Relaxation Fast Spin Echo sequence (FRFSE) and a T2-weighted FLuid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) were acquired.

Results

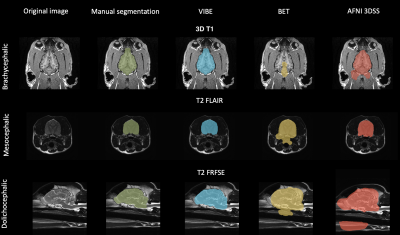

Our algorithm was tested and validated on a cohort of 30 dogs and 10 cats of different ages, sexes, breeds and cranial conformations. These animals did not show any sign of brain abnormalities. The canine cohort includes 10 brachycephalic, 10 mesocephalic and 10 dolicocephalic dogs. The feline cohort includes 10 European cats.To evaluate the quality of our segmentations, we compared the results with manually segmented masks verified by veterinary specialists and considered them as the ground truth. We used two similarity metrics to evaluate the output of our algorithm: the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and the Jaccard index.

To prove the robustness of our algorithm, we tested VIBE on three different sequences (3D T1-weighted images, T2-weighted FRFSE and T2 FLAIR), and compared the results to two other tools that are commonly used in the literature: BET3 from the FSL library and 3DSS from AFNI4.

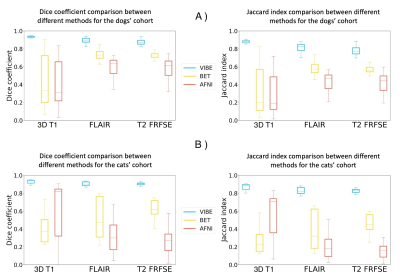

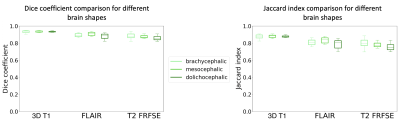

VIBE outperformed the other two methods and the results were uniform in all the tests performed. The average DSC is 0.90±0.02 for both cats and dogs cohorts, and the average Jaccard index is 0.81±0.04 for the dogs cohort (Fig. 2a) and 0.83±0.04 for the cats cohort (Fig. 2b) for the three MRI contrasts. The results were robust on all the different canine cranial conformations: brachycephalic, mesocephalic and dolicocephalic (Fig. 3).

VIBE was applied to the three anatomical planes (sagittal, dorsal, transverse) with no quality loss (Fig. 4). BET and 3DSS confirmed to be not adapted to veterinary brain extraction (Fig. 4), with an average DSC of 0.56±0.16 for BET and 0.46±0.2 for 3DSS (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The tests conducted on our cohorts prove the robustness of VIBE for the use on 3D and 2D MRI images of cats and dogs of all types of cranial conformations. VIBE was successfully applied to multiple MRI contrasts and anatomical planes, without any need to tune hyperparameters, making it fully automatic. VIBE can be extended to other animal species provided that a digital atlas exists in the literature.VIBE opens the possibility to enhance quantitative image processing in veterinary neuroimaging and will prove useful for multiple applications such as functional MRI brain studies, or mappings and brain tissues classifications to characterize brain pathologies.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Lohmeier J, Kaneko T, Hamm B, Makowski MR, Okano H. atlasBREX: Automated template-derived brain extraction in animal MRI. Scientific reports. 2019 Aug 21;9(1):1-9.

2. Milne ME, Steward C, Firestone SM, Long SN, O'Brien TJ, Moffat BA. Development of representative magnetic resonance imaging–based atlases of the canine brain and evaluation of three methods for atlas-based segmentation. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 2016 Apr 1;77(4):395-403.

3. Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human brain mapping. 2002 Nov;17(3):143-55.

4. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical research. 1996 Jun 1;29(3):162-73.

5. Johnson PJ, Luh WM, Rivard BC, Graham KL, White A, FitzMaurice M, Loftus JP, Barry EF. Stereotactic cortical atlas of the domestic canine brain. Scientific Reports. 2020 Mar 16;10(1):1-6.

6. Johnson PJ, Pascalau R, Luh WM, Raj A, Cerda-Gonzalez S, Barry EF. Stereotaxic diffusion tensor imaging white matter atlas for the in vivo domestic feline brain. Frontiers in neuroanatomy. 2020 Feb 11;14:1.

Figures