3757

Assessment of mouse brain creatine kinase rate using 31P-MRS at 7 Tesla1Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2Mouse Imaging Centre (MICe), Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Spectroscopy, Animals

31P-MRS experiments in mouse brain are scarce and often limited to ultra-high field scanners. We have recently reported that 31P-MRS is feasible in mouse brain at 7T as well. We now tested the potential of using saturation transfer experiments in the same setting to measure the creatine kinase rate in mouse brain.Introduction

Phosphorous-31 (31P) Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) is a powerful method to assess brain energy metabolism in vivo1. However, studies investigating mouse brain are scarce and often limited to ultra high-field scanners. We have previously reported that 31P-MRS is feasible at 7T for studying mouse brain energy metabolism2. We now bring this one step further to assess the feasibility of saturation transfer experiments to measure creatine kinase (CK) activity in vivo. For this, we compared the available protocol on the vendor’s machine with our implemented BISTRO (B1 insensitive selective train to obliterate signal scheme) sequence3 on phantom. By producing a gradual increase in the saturation pulse power, BISTRO has been shown to obtain a sharp saturation profile which can help reduce bleedover on adjacent resonances, particularly critical at long saturation times4. We then used our protocol to assess mouse brain phosphocreatine (PCr) to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) fluxes in vivo and identify potential sex-related differences.Methods

This study was performed with the approval of the local animal care and use committee. Eleven adult male (n=5) and female (n=6) C57BL/6J mice were scanned on a 7 Tesla (70/20) BioSpec MRI scanner (Bruker, Ettlingen, DE) under isoflurane anesthesia (1-2%). 31P-MRS was acquired using a dual tuned 31P/1H surface coil with a single 10mm 31P loop (PulseTeq Ltd, Chobham, UK) used as transceiver (Tx/Rx). Using the 1H-channel, a 210uL voxel (7x5x6mm3) was placed in the center of the brain using anatomical T2-weighted images (TurboRARE). Shimming was performed in the voxel to reach a water linewidth at half maximumh of 26±3Hz, followed by a 31P-MRS acquisition using 3D-ISIS (Npoints=1024, AcquisitionBW=40ppm, TR=8s). All pulses were optimized in phantoms to adjust the power for maximal signal Intensity. Progressive saturation transfer experiment was done using BISTRO sequence3, using a train of variable number of saturation modules. Each module (336 ms duration) consists of eight HS2 pulses (T=40ms, BW=100Hz) with variable RF power (with following scaling factors: 0.02, 0.04, 0.07, 0.14, 0.27, 0.49, 0.82, 1) applied at yATP offset, i.e. -2.50 ppm5. Saturation time was randomised at 5 different values (336, 672, 1’009, 2’018 and 4’710 ms) and control spectrum was acquired with a mirrored saturation at +2.50ppm. The saturation transfer experiments lasted ~2h per subject. Spectra were processed (phasing, B0-drift correction) in jMRUI and analysed with AMARES, using Lorentzian line-shape and constrained frequency, linewidth and amplitude for each component. A mono-exponential function was fitted (MATLAB) to the relative PCr signal decay as a function of saturation time (tsat) using the following equation: MPCr(tsat)/MPCr(0) = (1-k*T1)+k*T1*exp(-tsat/T1), to determine both k, the pseudo first-order forward reaction PCr->ATP rate constant (kPCr->ATP), and T1, the apparent T1 of PCr6. The pH was determined from the chemical shift difference between Pi and PCr on the averaged spectra for each mouse. All group statistics were done using Prism (GraphPad, Prism 9).Results

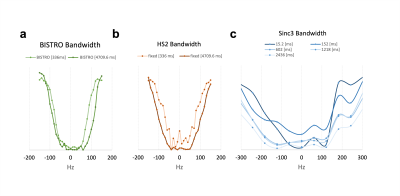

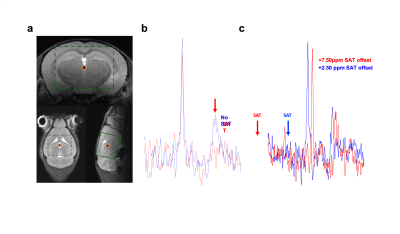

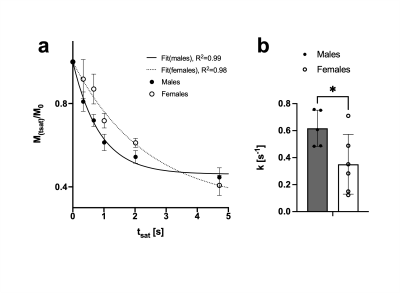

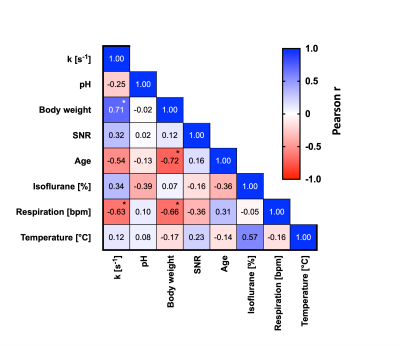

31P-MRS saturation pulses using BISTRO (Fig1.a, i.e. HS2 pulses with increasing amplitude) performed better in phantom compared to the HS2 pulses with constant amplitude (Fig1.b) or to the available version on the vendor’s system (e.g. using a Sinc3 saturation pulse, Fig 1.c). This was particularly critical at long saturation times. When applied in vivo (Fig2.a), BISTRO was able to effectively saturate the yATP signal (Fig2.b), while not causing any noticeable bleed-over in the control experiment at long saturation times (Fig2.c). This protocol was then applied to assess brain metabolic rate of ATP synthesis from PCr in adult C57BL/6 mice. While we found an overall kPCr->ATP of 0.47±0.22 [s-1] in mouse brain, we observed a significantly higher value (p=0.04, Fig3.a-b) for male mice (0.62±0.13 [s-1]) compared to females (0.35±0.22 [s-1]). Although no difference in physiological parameters was observed (%isoflurane dose, body temperature and breathing rate), male mice used in this study had higher body weight (+35%, p=0.0002) and were younger (-26%, p=0.0013). Importantly, the higher kPCr->ATP in male mice could not be attributed to a reduction in pH (n.s.), as CK forward reaction is pH dependent. Finally, strong correlations were observed (Fig.4) between kPCr->ATP and the body weight, age and respiration rate, suggesting the sex differences might have an indirect cause.Discussion

Our results confirm that saturation transfer experiments at 7T are feasible in mouse brain using BISTRO sequence. We report values of kPCr->ATP rate constant in mouse brain that are comparable to the only report to date acquired at 14.1 Tesla6. Furthermore, our protocol was able to identify variations in kPCr->ATP that might have an underlying biological origin. CK fluxes are known to be affected by age and by psychiatric disorders or neurodegenerative diseases7,8. While we observed sex differences in mouse brain, further investigations will determine whether they are related to body weight or age.Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements This work was supported by the Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging (WIN) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF)References

1 Lei, H. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 14409–14414 (2003) 2 Cherix, A et al. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30, (2022) 3 Luo, Y. et al. Magn. Reson. Med. 45, 1095–1102 (2001) 4 Horská, A. et al. Magma Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 5, 159–163 (1997) 5 Lee, B.-Y. et al. NMR Biomed. 31, e3842 (2018) 6 Mlynárik, V. et al. J. Alzheimers Dis. 31, S87–S99 (2012) 7 Andres, R. H. et al. Brain Res. Bull. 76, 329–343 (2008) 8 Allen, P. J. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1442–1462 (2012)Figures

Efficiency of BISTRO 31P-MRS saturation pulse in phantom at 7 Tesla.

a. The bandwidth of BISTRO saturation did not increase significantly compared to b. the similar pulse (HS2) with constant amplitude or c. the available pulses (e.g. Sinc3) on the vendor’s machine with constant amplitude.

BISTRO saturation performance in vivo.

a. Voxel position for in vivo 31P-MRS saturation transfer experiments. b. BISTRO was able to saturate yATP resonance in vivo and c. did not cause noticeable bleed-over on adjacent PCr resonance even at long saturation time (4.7s).

Forward CK rate constant assessment in mouse brain.

a. Exponential fit of PCr signal decay upon yATP saturation (fit of the group average). Data presented as Mean±SEM b. When fitting the PCr decay of each mouse individually as well, the determined CK rate constants were higher for males than for females (p=0.04). Data presented as mean±SD.

Correlation analysis between acquisition parameters.

Forward CK rate constant correlated highly with animal’s body weight, respiration rate and age, suggesting the underlying sex differences might have a broader biological and/or physiological explanation.