3745

Gastrointestinal MRI with Conscious Rats1University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Animals

Anesthesia has been required for preclinical gastrointestinal MRI but may confound gastric physiology. This study demonstrates, for the first time, the feasibility of gastrointestinal MRI with awake rats, and reports the effects of anesthesia on gastric motor function. Results suggest that awake rats show greater rates of gastric emptying and intestinal filling, and stronger gastric and intestinal motility relative to those anesthetized. Anesthesia with 2.5% isoflurane can entirely stop muscle contraction. The methods and findings reported herein lay the foundation for using awake GI-MRI in preclinical studies of gastrointestinal function or dysfunction.Purpose

For preclinical gastrointestinal (GI) MRI[1,2], anesthesia is required to help restrain animals from moving during MRI but may confound gastric physiology[3,4]. Although protocols have been established for awake animal functional MRI[5,6], similar protocols have never been attempted for GI MRI. The excessive body movement in an awake condition poses a much greater challenge for abdominal MRI than the head movement does for brain fMRI. This study aims to demonstrate the feasibility of GI MRI with conscious rats and compare the difference in gastric emptying, accommodation, and motility between the anesthetized and awake conditions.Methods

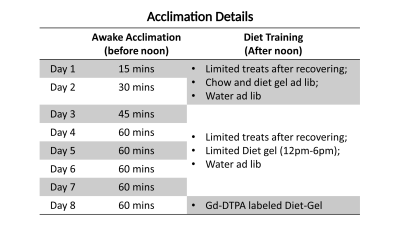

Ten Sprague-Dawley rats were trained to stay awake during GI MRI. To acclimate each animal to MRI, a mock scanner was constructed to mimic the dark, noisy, and restrained environment similar to the actual MRI system. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the animal was initially anesthetized and placed inside the mock scanner, while its body and brain were restrained by a customized apparatus. The anesthesia was then terminated for the animal to recover and stay awake for up to 1 hour while pre-recorded MRI scan sounds were played. The animal was monitored for its respiration, heart rate, oxygenation, temperature, and corticosteroid during or after the training. The training was repeated for 7 consecutive days with a progressive increase in the time of acclimation (Fig. 2). Following the training, each animal consumed a gadolinium-DTPA-labeled diet-gel meal (~5 g) after overnight fasting[1]. Then it was placed inside a 7-Tesla MRI system for GI-MRI[2]. Each animal was scanned for about 90 mins, during which the animal was anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane for the first and last 15 mins and transitioned to or stayed in wakefulness for the time in between. A 2-D gradient echo sequence was used to acquire dynamic T1-weighted images (TR = 11.5 ms, TE = 1.8 ms, 24 slices of 1.5mm thickness, in-plane resolution = 0.5 mm x 0.5 mm, FOV = 64 mm x 42 mm, with spatial saturation and free breathing, 300 repetitions at 1.8 s per repetition). On a separate day, the same animal was scanned for GI MRI again while it was lightly anesthetized with isoflurane (0.5% through nose cone) and dexmedetomidine (0.01mg/ml, 0.025 mg/kg/h through SC infusion). For analysis, we evaluated the rate of gastric emptying, the luminal distribution of the ingested food, and muscle contraction (also known as gastric motility), and compared each of these measures between the awake and anesthetized conditions for 6 out of the 10 animals.Results

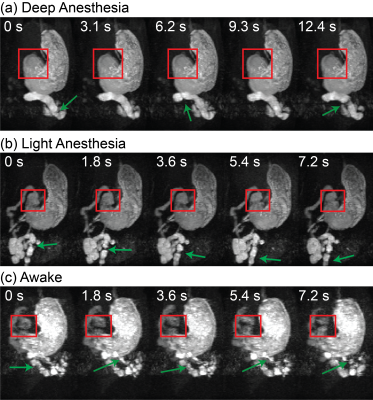

The awake training could acclimate the animals to MRI, while the physiological signals did not indicate any excessive stress or body movement. During GI MRI, the animals remained awake for 50-60 mins while the respiratory rate was about 91.8 ± 3.1 cycles per minute without any sign of significant stress. GI MRI showed the contrast-enhanced luminal content in both the stomach and the intestines (Fig. 3.a and 3.b). At ~50 mins into the MRI experiment, the stomach volume was reduced by 35.62% ± 3.35% when the animals were awake, significantly greater than the 18.69% ± 4.02% of emptying in the anesthetized condition (paired t-test, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3.c). The intestinal volume increased by 27.49% ± 16.44% in the awake condition, compared with a decrease of 18.69% ± 4.02% in the anesthetized condition (Fig. 3.d). The proximal and distal stomach showed a disproportionate volume reduction in the awake condition, but not in the anesthetized condition. When awake, the volume reduction after ~50 mins was greater in the distal stomach than the proximal stomach (Fig. 4). Importantly, anesthesia also affected gastric motility. Antral contractions were completely stopped by 2.5% isoflurane, reduced by 0.5% isoflurane, whereas the contractions were stronger and more occlusive in the awake condition (Fig. 5). Similar effects were also observed for the intestinal contractions (Fig. 5).Conclusions

For the first time, we report an effective acclimation protocol for GI MRI with conscious rats. GI MRI following a contrast-labeled meal reveals considerable distinctions in the postprandial gastrointestinal motility, emptying, and accommodation between the awake and anesthetized conditions. Awake rats show greater rates of gastric emptying and intestinal filling, and stronger gastric and intestinal motility relative to those anesthetized. Deep anesthesia can entirely cease gastric motility. The methods and findings reported herein lay the foundation for using awake GI-MRI in preclinical studies of gastrointestinal function or dysfunction.Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH R01AT011665.References

[1] Lu, Kun-Han, Jiayue Cao, Steven Thomas Oleson, Terry L. Powley, and Zhongming Liu. "Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of gastric emptying and motility in rats." IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 64, no. 11 (2017): 2546-2554.

[2] Wang, Xiaokai, Jiayue Cao, Kuan Han, Minkyu Choi, Yushi She, Ulrich Scheven, Recep Avci et al. "Surface-based Characterization of Gastric Anatomy and Motility using Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Neural Ordinary Differential Equation." bioRxiv (2022).

[3] Ailiani, A. C., T. Neuberger, J. G. Brasseur, G. Banco, Y. Wang, N. B. Smith, and A. G. Webb. "Quantifying the effects of inactin vs Isoflurane anesthesia on gastrointestinal motility in rats using dynamic magnetic resonance imaging and spatio‐temporal maps." Neurogastroenterology & Motility 26, no. 10 (2014): 1477-1486.

[4] Torjman, Marc C., Jeffrey I. Joseph, Carey Munsick, M. Morishita, and Zvika Grunwald. "Effects of isoflurane on gastrointestinal motility after brief exposure in rats." International journal of pharmaceutics 294, no. 1-2 (2005): 65-71.

[5] Ferris, Craig F. "Applications in Awake Animal Magnetic Resonance Imaging." Frontiers in Neuroscience 16 (2022).

[6] Liang, Zhifeng, Jean King, and Nanyin Zhang. "Uncovering intrinsic connectional architecture of functional networks in awake rat brain." Journal of Neuroscience 31, no. 10 (2011): 3776-3783.

Figures