3720

Universal sequence-invariant deep learning image reconstruction for cardiovascular MR Multitasking1Biomedical Imaging Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Department of Bioengineering, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Quantitative Imaging

Cardiovascular MR (CMR) Multitasking can quantify various parameter combinations without breath-holding or ECG monitoring. Clinically practical reconstruction time is viable using supervised deep subspace learning, but it depends on sequence-specific training. Here we explore whether universal, sequence-invariant CMR Multitasking deep learning reconstruction is practical by trading temporal awareness (breadth) for added depth in spatial domain. We evaluated the performance and generalizability of both strategies by training on T1 mapping data only and testing on two datasets: a) a matched-sequence T1 mapping data; and b) a novel-sequence T1-T2 mapping data.Introduction

CMR Multitasking [1] is capable of quantitative CMR imaging of various parameter combinations without relying on breath-holding or ECG monitoring. Clinically practical reconstruction times are possible with supervised deep subspace learning [2-5], but currently relies on a sequence-specific training paradigm. This unfortunately requires that each parameter combination is trained separately, and only once enough training data have been acquired. Here we explore whether universal, sequence-invariant deep learning reconstruction is feasible for CMR Multitasking, by trading the parameter-sensitive temporal awareness of the existing spatiotemporal “multi-component” (MC) network structure for additional depth in a spatial-only “component-by-component” (CBC) network. In this study, we assessed the performance and generalizability of these two network structures by training both networks on T1 mapping data only, then testing in two scenarios: 1) on matched-sequence T1-mapping data; and 2) on novel-sequence T1-T2 mapping data.Methods

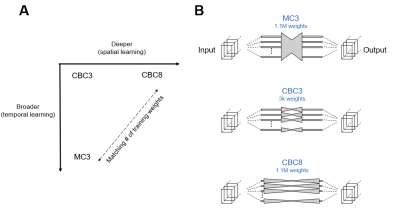

Network structures: Three different U-Net [6] structures were evaluated (Figure 1):1. MC3 (spatiotemporally-aware, 3 downsampling steps, 1.1M parameters) [3],

2. CBC3 (spatially-aware, 3 downsampling steps, 3k parameters)

3. CBC8 (spatially-aware, 8 downsampling steps, 1.1M parameters).

An 8-downsampling step MC was not evaluated due to computational infeasibility and expectation of overfitting.

Training and validation data: All three networks were trained on T1 mapping CMR Multitasking data collected from three 3T Siemens scanners (Verio, mMR, and Vida), including 118 cases for training along with 13 cases for validation. Imaging parameters were 1.7 mm in-plane spatial resolution, 8 mm slice thickness, 20 cardiac phases, and 6 respiratory phases. The matrix size of the spatial factor is 320×320×32.

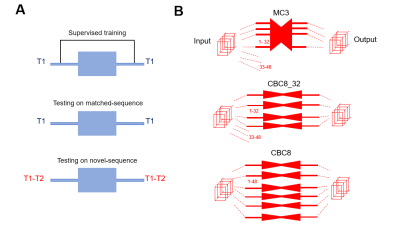

Testing data: The first group of n=15 testing data (T1-only) was collected with the same parameters and sequence as training and validation data. The second group of n=20 testing data (T1-T2) was collected with similar parameters, but a different sequence with additional T2 preparation modules [1]. The subspace dimension was also larger, with spatial factor size 320×320×48.

Network comparison: We first determined the impact of removing temporal awareness (MC3 to CBC3), followed by the impact of trading that temporal awareness for spatial depth (MC3 to CBC8) in the 15 T1-only testing datasets. We then assessed the generalizability of both MC3 and CBC8 networks to a different pulse sequence by testing the T1-trained networks on 20 testing datasets collected using novel T1-T2 pulse sequence with an additional contrast dimension (T2).

As Figure 2B shows, the number of components of T1-T2 data (48) is different from that of T1 only data (32). Thus, the fixed-rank MC3 can only be applied to the first 32 components of T1-T2 testing sets, unlike the more flexible CBC network which can be applied to arbitrary numbers of components. We controlled for the effects of MC3 rank-truncation by evaluating two CBC variations: one truncated to the same first 32 components (CBC8_32), and one applied to all 48 components (CBC8).

Evaluation methods: Normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE) of the images was calculated using the iteratively reconstructed images as a reference. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare performance between networks and the Mann–Whitney U test to compare the performance of each network between different testing datasets. In both cases, we regarded p<0.05 as statistically significant. Bland-Altman plots were used to evaluate accuracy and precision of end-diastolic myocardial T1 and T2 values in both testing data sets versus the corresponding T1 and T2 values from iterative reconstruction.

Results and Discussions

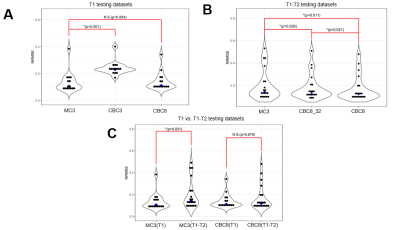

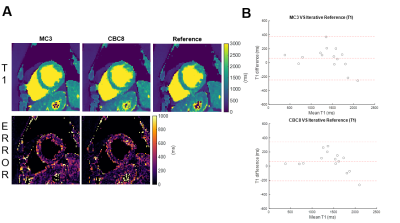

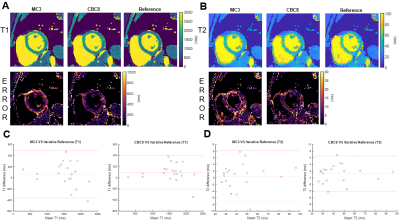

Figure 3 shows network performance in the testing data. In T1 data (Figure 3A), CBC3 produced higher NRMSE than MC3, but there was no significant difference between CBC8 and MC3 NRMSE, suggesting that temporal awareness can be replaced by spatial depth. In T1-T2 data (Figure 3B), CBC8 and CBC8_32 both outperformed MC3, with CBC8 performing best, indicating that the benefits of CBC8 are partially due to its subspace-dimension flexibility and partially due to its different internal structure. Notably, MC3 performance degraded when switching from T1 testing data to T1-T2 testing data, whereas CBC8 performance did not significantly change (Figure 3C), thus indicating the generalizability of CBC8. For T1 maps, CBC8 had 15% tighter limits of agreement (LoA) against reference T1 maps than MC3 (Figure 4). For T1-T2 maps, CBC8 produced fewer structural features in error maps and tighter LoA by 29% in T1 and 32% in T2 than MC3 (Figure 5). Both results indicate better quantitative precision of CBC8 over MC3.Conclusions

Trading temporal awareness for additional spatial depth maintained performance in T1 mapping CMR Multitasking image reconstruction and allowed generalization to T1-T2 mapping without requiring de novo training. If the generalizability of CBC networks further extends across multiple clinical sites, scanner vendors, and field strengths, it may be an important asset in clinical settings.Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by NIH R01 EB028146.References

[1] A. G. Christodoulou et al., "Magnetic resonance multitasking for motion-resolved quantitative cardiovascular imaging," Nature biomedical engineering, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 215-226, 2018.

[2] Y. Chen, J. L. Shaw, Y. Xie, D. Li, and A. G. Christodoulou, "Deep learning within a priori temporal feature spaces for large-scale dynamic MR image reconstruction: Application to 5-D cardiac MR Multitasking," in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 2019: Springer, pp. 495-504.

[3] Z. Chen, Y. Chen, Y. Xie, D. Li, and A. G. Christodoulou, “Data-consistent Non-Cartesian deep subspace learning for efficient dynamic MR image reconstruction,” 2022 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 2022.

[4] C. M. Sandino, F. Ong, and S. S. Vasanawala, "Deep subspace learning: Enhancing speed and scalability of deep learning-based reconstruction of dynamic imaging data," Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med, 2020.

[5] C. M. Sandino, P. Lai, S. S. Vasanawala, and J. Y. Cheng, "Accelerating cardiac cine MRI using a deep learning‐based ESPIRiT reconstruction," Magn Reson Med, vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 152-167, 2021.

[6] O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, and T. Brox, "U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation," Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv, pp. 234-241, 2015.

Figures