3711

PIFN EPT: MR-Based Electrical Property Tomography Using Physics-Informed Fourier Networks1Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, United States, 2Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States, 3Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 4Bernard and Irene Schwartz Center for Biomedical Imaging (CBI), Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 5Department of Statistics and Applied Probability, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Electromagnetic Tissue Properties

We introduce physics-informed Fourier networks (PIFNs) for Electrical Properties (EP) Tomography (EPT). Our novel deep learning-based method is capable of learning EPs globally from noisy magnetic resonance (MR) measurements, i.e, the magnitude of the magnetic transmit field and the transceive phase. Our proposed method also provides noise-free transmit field reconstructions. Two separate Fourier neural networks are used to efficiently estimate the transmit field and EPs at any location. We show that PIFN EPT accurately infers the EPs distribution of an inhomogeneous phantom from noisy simulated measurements.Introduction

Electrical properties (EP), namely permittivity and electric conductivity, determine the interactions between electromagnetic waves and biological tissues[1]. EPs are biomarkers for pathology characterization, such as cancer, and can provide important information in the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures[2]. Magnetic resonance-based electrical properties tomography[3] (MR-EPT) uses MR measurements, such as the magnetic transmit or receive fields $$$(B_{1}^{+}, B_{1}^{-})$$$ to reconstruct EP maps. These reconstructions rely on the calculations of spatial derivatives of the measured $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ or $$$B_{1}^{-}$$$. However, the numerical approximation of derivatives leads to noise amplifications that introduce errors and artifacts in the reconstructions[4]. Other methods that do not use differential operators, such as Global Maxwell Tomography[5], are more robust to noise but they require multiple transmit field maps and a high computation time for a successful implementation. In this work, we leveraged recent developments on physics-informed deep learning[6] and Fourier features mapping[7] to learn the EP distribution from simulated $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ maps, corrupted with high levels of noise. We developed novel physics-informed Fourier network (PIFN) algorithms that are constrained by the generalized Helmholtz equation to effectively de-noise the $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ and accurately reconstruct the EPs at any spatial resolution.Theory and Methods

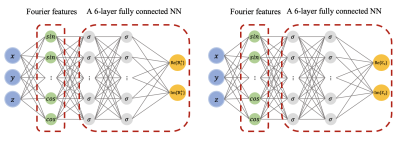

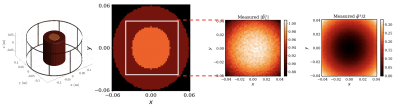

For an RF birdcage coil (Figure 2 left) and 3 tesla MRI frequency, $$$B_{z}$$$ can be assumed zero around the mid-plane of the coil. Resultantly, the relationship between the $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ and the underlying EPs can be described by the generalized Helmholtz equation $$$\nabla^2 B_1^{+} + k_{0}^2 \varepsilon_c B_1^{+} -\left(\frac{\partial B_1^{+}}{\partial x}-i \frac{\partial B_1^{+}}{\partial y}\right)\left(g_x+i g_y\right) -\frac{\partial B_1^{+}}{\partial z} \cdot g_z = 0$$$, where $$$k_{0}$$$ is the wave number in free space, $$$\varepsilon_c$$$ is the relative complex permittivity and $$$\boldsymbol{g}:=(g_x, g_y, g_z):=\nabla \ln \varepsilon_c$$$. We defined a neural network (NN) $$$\mathcal{B}_{1}^{+}(\boldsymbol{r};\boldsymbol{\theta_{1}})$$$, parameterized by a set of weights and biases $$$\boldsymbol{\theta_{1}}$$$, to estimate the complex $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ fields. We used an additional NN $$$\mathcal{E}_{c}(\boldsymbol{r};\boldsymbol{\theta_{2}})$$$ with independent weights and biases $$$\boldsymbol{\theta_{2}}$$$ to estimate the distribution of relative complex permittivity. As a result, the generalized Helmholtz equation transforms to a PDE residual that can be represented with two NNs, where the derivatives w.r.t the spatial coordinates can be computed using automatic differentiation[9]. The parameters of two NNs are learned via gradient descent using a composite loss function of two terms: a) A data mismatch term between the outputs of $$$\mathcal{B}_{1}^{+}$$$ and the measurements and b) The average of the norm of the PDE residual over all training points. In this work, $$$\mathcal{B}_{1}^{+}$$$ and $$$\mathcal{E}_{c}$$$ were constructed independently using a Fourier features mapping[7] as a coordinate embedding of the input followed by a fully-connected NN with 6 layers, 128 units per layer, and a sine activation function (Figure 1). Such architecture enables NNs to learn high frequency components more effectively. Here a random Fourier feature mapping is defined as $$$\gamma(\boldsymbol{r})=\left[\cos (\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{r}), sin (\boldsymbol{B r})\right]^{\rm T}$$$, where each entry of $$$\boldsymbol{B} \in R^{64 \times 3}$$$ is sampled from a Gaussian distribution $$$\mathcal{N}(0,\sigma_{0}^{2})$$$. We chose $$$\sigma_{0}$$$ to be $$$40$$$ and $$$2$$$ for $$$\mathcal{B}_{1}^{+}$$$ and $$$\mathcal{E}_{c}$$$, respectively. We trained the NNs jointly by minimizing the defined loss using the Adam optimizer for 120k iterations in total, with a decaying schedule of learning rates $$$10^{-3}, 10^{-4}, 10^{-5}$$$, decreased every 40k iterations.We used the volume-surface integral equation method[8] to simulate the circularly polarized (CP) mode of a birdcage coil loaded with an inhomogeneous concentric cylindrical phantom with permittivity $$$\varepsilon_{r}=\{70, 78\}$$$ and conductivity $$$\sigma=\{0.5, 1\}$$$. The radius and length of the cylinder were 6cm and 14cm, respectively and the radius of the inner compartment was 3cm. We used the $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ and $$$B_{1}^{-}$$$ from the 8cm x 8cm x 2cm (18,491 voxels, 2mm resolution) central region of the cylinder (white square in the middle left of Figure 2) and corrupted then with Gaussian noise of peak signal-to-noise-ratio of 200. We approximated the complex $$$B_1^{+}$$$ using the transceive phase assumption and constructed the synthetic measurements $$$\{(\boldsymbol{r_{i}}, |\tilde{B_{1}^{+}}(\boldsymbol{r_{i}})|, \tilde{\varphi^{\pm}}(\boldsymbol{r_{i}})\}_{i=1}^{N}$$$ at $$$N=18,491$$$ 3D location $$$\boldsymbol{r_{i}} = (x_{i}, y_{i}, z_{i})$$$ (Figure 2 middle right and right).

Results

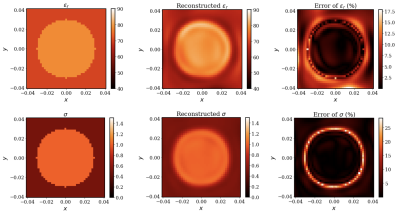

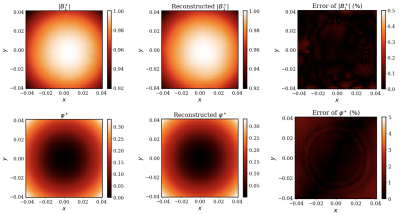

Once trained, the resulting PIFNs $$$\mathcal{B}_{1}^{+}$$$ and $$$\mathcal{E}_{c}$$$ can be used to obtain physically consistent predictions of $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ and EP at any location. For the central axial cut, Figures 3 and 4 show the predicted EPs and reconstructed $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ (middle) and the peak normalized absolute error (PNAE) of the predicted EPs and reconstructed $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ (right), respectively. The average value of the error over the extracted volume was $$$0.19\%, 4.56\%$$$ and $$$4.04\%$$$ for the $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$, relative permittivity and conductivity, respectively.Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we have proposed PIFN EPT, a novel deep learning-based method that is capable of learning accurate EP distribution of inhomogeneous phantoms from simulated MR measurements, corrupted with high levels of noise and reconstructing a noise-free $$$B_{1}^{+}$$$ approximation simultaneously. As shown in Figure 3, the boundary artifacts of the EP reconstructions are not as severe as other EPT methods[3], and we can clearly distinguish the two compartments of the cylinder. In future work, we will investigate the performance of the proposed algorithms with realistic head models in simulation and perform experimental validation.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSF # 2107321 and NIH R01 EB024536.References

[1] Hand, J. W. “Modelling the interaction of electromagnetic fields (10 MHz–10 GHz) with the human body: methods and applications.” Physics in Medicine $$$\&$$$ Biology 53.16 (2008): R243.

[2] Rossmann, Christian, and Dieter Haemmerich. "Review of temperature dependence of thermal properties, dielectric properties, and perfusion of biological tissues at hyperthermic and ablation temperatures." Critical Reviews™ in Biomedical Engineering 42.6 (2014).

[3] Katscher, Ulrich, et al. “Determination of electric conductivity and local SAR via B1 mapping.” IEEE transactions on medical imaging 28.9 (2009): 1365-1374.

[4] Mandija, Stefano, et al. “Error analysis of Helmholtz-based MR-electrical properties tomography.” Magnetic resonance in medicine 80.1 (2018): 90-100.

[5] Serrallés, José EC, et al. "Noninvasive estimation of electrical properties from magnetic resonance measurements via global Maxwell tomography and match regularization." IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 67.1 (2019): 3-15.

[6] Raissi, Maziar, Paris Perdikaris, and George E. Karniadakis. "Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations." Journal of Computational physics 378 (2019): 686-707.

[7] Tancik, Matthew, et al. "Fourier features let networks learn high frequency functions in low dimensional domains." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020): 7537-7547.

[8] Giannakopoulos, Ilias I., et al. "A hybrid volume-surface integral equation method for rapid electromagnetic simulations in MRI." IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering Early Access (2022).

[9] Baydin, Atilim Gunes, et al. “Automatic differentiation in machine learning: a survey.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 18 (2018): 1-43.

Figures