3709

U-JET: Preliminary results of a convolutional neural network approach for distortion-free image reconstruction of PROPELLER data1Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Medicine MEVIS, Bremen, Germany, 2mediri GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, 3Faculty 1 (Physics/Electrical Engineering), University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Artifacts

Arterial Spin Labeling has great potential in clinics as a non-invasive alternative to Dynamic Contrast Enhanced imaging. However, motion sensitivity needs to be tackled by readout techniques such as 3D GRASE PROPELLER, which unfortunately shows a high sensitivity to geometric distortion. Analytical separation of motion and distortion effects is computationally demanding and might fail in some situations. To this aim, a U-NET based convolutional neural network approach is demonstrated which might overcome this limitation.Introduction

Non-invasive Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) perfusion imaging has the potential to become an alternative to invasive techniques such as DCE in clinical practice. However, ASL shows a high sensitivity to subject motion which is common in clinical reality1. Therefore, robust motion correction techniques are a must to pave the way of ASL into the clinics. It was recently shown, that pseudo-continuous ASL in combination with a 3D GRASE PROPELLER readout and an optimized reconstruction procedure allows a joint estimation and correction of motion and geometric distortion (3DGP-JET)2. However, computational demands were high and strong distortion arising e.g., from residual unsuppressed fat signal was likely to be missed by the algorithm. We propose that these limitations can be overcome by substituting the analytical JET algorithm by a U-NET3 based convolutional neural network which aims for artifact-free combination of individual PROPELLER blades (U-JET). To this aim, we demonstrate the application of U-JET on simulated PROPELLER data with different levels of geometric distortion.Methods

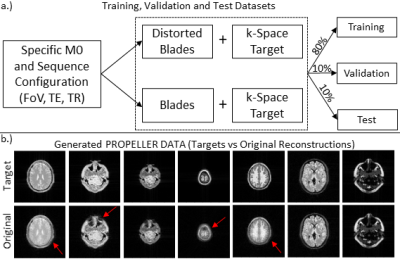

Data generationTraining data were generated using Jemris4. Therefore, a spin-echo EPI PROPELLER sequence was designed, which shows the same in-plane distortion characteristics as other EPI-based PROPELLER sequences such as 3DGP. Fixed simulated sequence parameters were: acquisition matrix = 96x32, blades = 10 (golden-angle increment) and echo spacing = 0.7ms. Additional parameters were selected randomly in given ranges to introduce variations in contrast and object size: TE = [50-99] ms, TR = [3000-6000] ms, FoV = [250-500] mm2. For each simulation, one of 165 2D brain slice phantoms was randomly selected. Additional contrast variation was achieved by modulating the M0 value based on simulated signal intensities resulting from an initial saturation pulse with two randomly timed inversion pulses (assumed inflow time TI=3600 ms) as typically applied during ASL experiments. Finally, the off-resonance map (1.5 T) was modulated with a random factor (0 to 0.5) to introduce various levels of image distortion. Simulations were performed twice, with and without the off-resonance map. After gridding, blades without distortion were combined to form the target k-space data (cf. Fig. 1). Note that that the matrix size of gridded blades was cropped to 64x64 pixels to speed up the network training in this work. For each M0 + sequence parameters setup, the undistorted as well as the distorted blades together with the undistorted target reconstruction were sorted into training, test and validation sets based on an 80:10:10 split (cf. Fig. 2a). In total 1104 pairs (input+target) were split into 888 training, 106 validation and 110 test datasets. Each input as well as target dataset was normalized to values between 0 and 1.

Training of U-JET model

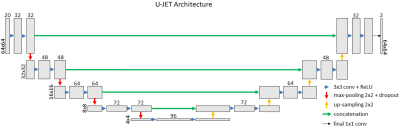

The model architecture as implemented in TensorFlow5 is demonstrated in Fig. 3 and follows the classical U-NET shape3. Complex-valued blades were split into real and imaginary parts which were subsequently distributed along the channel dimension to form a 64x64x2 matrix for each blade. Matrices from all 10 blades were concatenated to form a 64x64x20 input. After processed by U-JET, a 64x64x2 matrix was generated with real and imaginary parts spread along the third dimension, corresponding to the combined k-space. Optimization was accomplished using the Adam optimizer with a mean-squared error (MSE) loss function.

Results

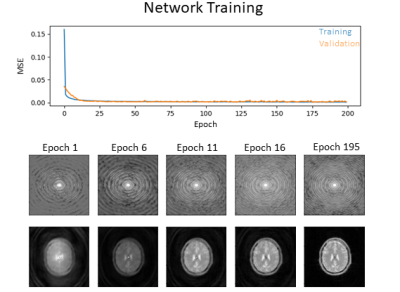

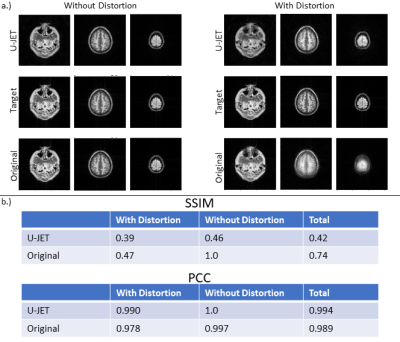

Fig. 2b exemplarily shows the variation of images in the generated data pool, indicating different levels of geometric distortion, signal-to-noise ratio, field of view as well as image contrast. The evolution of the loss function for the training and validation dataset and the evolution of combined k-space data are shown in Fig. 4. Fig. 5 shows example images from the test dataset which were reconstructed using the original PROPELLER algorithm and the U-JET network. In addition, image quality metrics in terms of the structural similarity index (SSIM) and the Pearson-Cross-Correlation (PCC) are given.Discussion

The U-JET model was able to visually reduce geometric distortion in the test data (cf. Fig. 5). While this is also evident from increased Pearson-Correlation-Coefficients (PCC) between target and predicted images, the structural similarity index (SSIM) is decreased, which could result from scaling differences between the images, being further investigated in future work. The generalizability of the network will also be further investigated by adding real MR data to the test dataset. Here, data from abdominal organs such as liver should be incoporated, because strong distortion arising from shifted fat signal prevents succesfull application of PROPELLER ASL in these regions so far and the proposed algorithm could overcome this limitation. We also propose to investigate different loss functions being more suited for k-space data than MSE. Note, that additional motion should not be simulated by rotating individual blades but needs to be incorporated into the simulation process to prevent violation of the physical properties of geometric distortion in combination with subject motion. Finally, this work can be seen as a promising starting point to investigate data-driven artifact-free reconstruction of 3D GRASE PROPELLER data to allow robust ASL imaging.Conclusion

The presented U-JET allowed the visual reduction of distortion artifacts in reconstructed Spin-Echo EPI PROPELLER images. Quantitatively, this resulted in an increased Pearson-Correlation-Coeffecient between target and reconstruction when compard with the standard algorithm. Structural similiraty indices were however reduced, which will be further investigated.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Jalal B Andre, Brian W Bresnahan, Mahmud Mossa-Basha et al., Toward quantifying the prevalence, severity, and cost associated with patient motion during clinical MR examinations, J Am Coll Radiol. 2015 Jul;12(7):689-95

2. Jörn Huber, Daniel Christopher Hoinkiss, Matthias Günther., Joint estimation and correction of motion and geometric distortion in segmented arterial spin labeling, Magn Reson Med. 2022 Apr;87(4):1876-1885.

3. Ronneberger et al., U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention -- MICCAI, 2015

4. Tony Stöcker, Kaveh Vahedipour, Daniel Pflugfelder et al., High-performance computing MRI simulations, Magn Reson Med. 2010 Jul;64(1):186-93

5. Abadi et al., TensorFlow: a system for large-scale machine learning, OSDI, 2016

Figures