3673

Using laminar fMRI and modeling to study auditory predictive processing1Deparment of Cognitive Neuroscience, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 2Center for Magnetic Resonance Research, Minneapolis, MN, United States, 3University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, United States, 4New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 5Center for Cognitive Neuroscience Berlin, Free University Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 6Department of Neurology, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 7Department of Neurophysiology, Max-Planck Institute for Brain Research, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 8Joint Department of Medical Imaging and Krembil Brain Institute, Techna Institute & Koerner Scientist in MR Imaging, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI (task based), High-Field MRI

We use ultra-high field fMRI to explore the differential role of cortical layers in the information flow between top-down predictions and bottom up sensory evidence in a predictive coding (PC) framework. As the measured BOLD signal is affected by vascular draining, we use a computational model that combines neuronal dynamics with laminar vascular physiology to help us understand prediction signals at cortical depths and underlying neuronal responses. We show that a violation in prediction caused response modulation in superficial and deep layers in the primary auditory cortex, which is in line with the PC framework.Introduction

Predictive coding postulates that our brains build an internal representation of the sensory world through the comparison of predictions casted by an internal model and the sensory input. Such a process takes place throughout the (sub-) cortical hierarchy attributing a specific role to the different cortical layers in the information flow between top-down predictions and bottom-up sensory1,2 We use ultra-high field fMRI (7 Tesla) to investigate the role of cortical layers in response to tones that either respect or deviate from contextual cues using BOLD fMRI. However, the effect of draining veins renders laminar gradient-echo BOLD activity tainted, as responses increase toward the gray matter surface making it difficult to disentangle neuronal from vascular dynamics3. Here we address this issue using a computational model4,5 that combines neuronal dynamics and laminar vascular physiology within a dynamic causal modeling (DCM) framework. Using this model, we aim to account for draining effects and understand neuronal counterparts for the prediction signals measured at various cortical depths.Methods

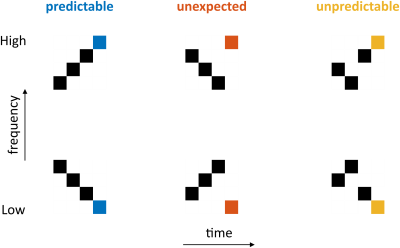

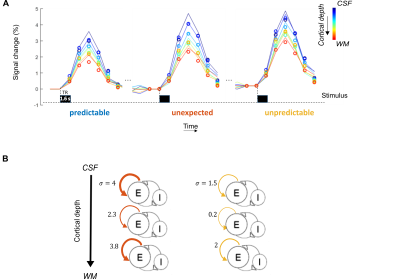

Experimental DesignParticipants passively listened to six sequences consisting of four tones (Fig 1). The first three tones can (when ordered) give rise to predictions and elicit specific expectations about the fourth tone (expected - predictable sequence). Violating these expectations gives rise to deviant responses (unexpected sequence) and when the first three tones are not presented in a specific order (unpredictable sequence), predictions are reduced.

MRI parameters

Ten participants were scanned using a 7 Tesla Siemens Magnetom MRI scanner. Whole-brain anatomical T1-weighted images were collected using a Magnetisation Prepared 2 Rapid Acquisition Gradient Echo (MP2RAGE) sequence at a resolution of 0.75 mm isotropic. Functional T2*-weighted data was obtained with multiband (MB) Gradient Echo- Echo Planar Imaging (GE-EPI) collected at a resolution of 0.8 mm isotropic (TR = 1.6 s, TE = 26 ms, MB = 2, iPAT = 3, flip angle = 90 degrees, field of view: 170 x 170 mm, matrix size: 212 x 212). For each participant, we collected between 6 and 8 runs.

Model

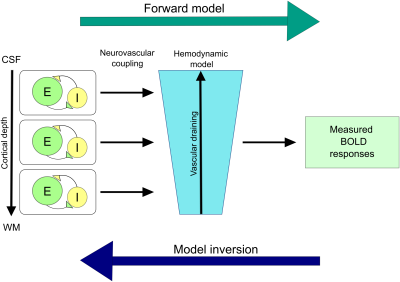

The compartmental model4,5 contains a neuronal population model (of excitatory and inhibitory neurons at three cortical depths) and a model of the neurovascular coupling at laminar level. This (forward) model allows generating laminar BOLD responses (Fig 2). Model inversion allows us to account for vascular draining and estimate the modulation of parameters of the neuronal model in dependence with the experimental conditions. We tested 8 models, each depicting external modulation of excitatory neuronal populations (i.e., due to the violation of predictions) at either superficial/middle/deep layers, or a combination of any two, all three, or none. The data was sampled at various cortical depths and after Bayesian parameter averaging, the best model was computed by comparing posterior probabilities.

Data preprocessing

Pre-processing was done in BrainVoyager (Brain Innovation, Maastricht, The Netherlands, version 21.4), which included slice scan time correction using sinc interpolation, motion correction using intrasession alignment to the first run and temporal low-pass filtering. Functional data were coregistered to the anatomical T1-weighted data using boundary based registration. High-resolution, manually corrected segmentations were used to create mid-gray matter surfaces on which we drew ROI’s (Heschl’s Gyrus, Planum Polare, Planum Temporale, anterior and posterior Superior Temporal Gyrus). These ROI’s and the cortical depth estimates (sampled at 7, 9, 10 and 11 layers) of the functional data were used to invert the model and estimate in each ROI the influence of our experimental manipulation on local neural population dynamics.

Results

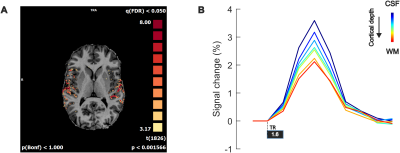

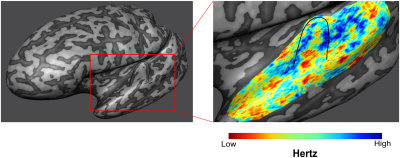

Our stimuli elicited stable responses in bilateral auditory cortex (Fig 3A), resulting in measurable laminar BOLD responses (Fig 3B). As sequences are presented to generate expectations of both high and low frequency tones, we can map frequency preference (Fig 4). We show measured and fitted laminar BOLD responses (Fig 5A). Moreover, our modeling approach shows that in Heschl’s Gyrus the response to unexpected (deviant) stimuli (compared to predictable ones) is best explained by a model that includes the modulation of responses at all cortical layers with parameter estimates showing a stronger modulation in superficial and deep layers in comparison to the middle layer. The response to tones in absence of a stable prediction (compared to predictable ones) also results in a modulation of superficial and deep layers, albeit to a lower level compared to the deviant condition (Fig 5B).Discussion

Our results show that violating a prediction results in overall increased responses in Heschl’s Gyrus. After Bayesian model comparison, we found that the model best fitting the measured responses is one in which deviant responses modulate responses in superficial and deep layers. These results are in line with the PC framework1,2,6.Conclusion

We show the first indication of cortical depth dependent predictive processing in the human primary auditory cortex using laminar fMRI. This work can be extended by including higher-order areas and investigating the hierarchical information exchange between areas. This will aid us in understanding how the brain processes contextual information and how the brain deals with unexpected events in our environment.Acknowledgements

Funding: LKF, IZ, LV, LM, KU, EY and FDM were funded by the National Institute for Health grant RF1MH116978-01. FDM was additionally funded by the National Institute for Health grant RF1MH116978-01 and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 101001270.

Ethics: The scanning procedures have been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for human subject research at the University of Minnesota. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before commencement of the measurements.

References

[1] Bastos A, Usrey M, Adams R, et al. Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron. 2012;76(4). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.038.

[2] De Lange F, Heilbron M, Kok P. How do expectations shape perception? Trends in Cogn Sci. 2018;22(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.06.002

[3] Turner R. How much can a vein durian? Downstream dilution of activation-related cerebral blood oxygenation changes. NeuroImage. 2002;16. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2002.1082

[4] Havlicek M, & Uludag K. A dynamical model of the laminar BOLD response. NeuroImage. 2020;204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116209

[5] Uludag K & Havlicek M. Determining laminar neuronal activity from BOLD fMRI using a generative model. Progress in Neurobiology, 2021;207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102055

[6] Heilbron M & Chait M. Great Expectations: Is there Evidence for Predictive Coding in Auditory Cortex? Neuroscience. 2018;389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.07.061.

Figures