3666

Application of SLR pulses to short-TR spin-echo fMRI at 7T: SNR considerations and a direct demonstration of reduced cardiac noise1Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 2Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 3Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 4University of Ottawa Institute of Mental Health Research, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 5Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 6Institute of Imaging Science, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 7Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI, RF Pulse Design & Fields, Ultra-High-Field MRI

We show that SLR pulses provide much better slice profiles (and thus much higher SNR) than standard sinc pulses for short-TR spin-echo (SE) acquisitions, even when there is substantial B1+ inhomogeneity. As one application, we used SLR pulses and a TR of 300 ms in SE-EPI acquisitions at 7T, enabling the “direct” measurement of cardiac frequencies at ~1 Hz without aliasing. Far less cardiac fluctuation was seen in SE- versus GE-EPI data. While SE-fMRI is known to have reduced macrovascular weighting and thus improved spatial specificity relative to GE-fMRI, our results suggest that it may also have better temporal specificity.Introduction

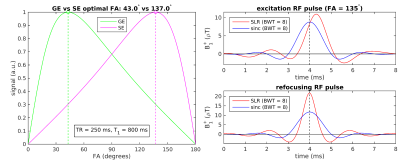

While the optimal (Ernst) flip angle αGE for a gradient-echo (GE) acquisition is ≤ 90°, the optimal excitation flip angle αSE for a spin-echo (SE) acquisition with the same TR/T1 is 180°− αGE, assuming a 180° refocusing pulse[1–3]. For short TRs, this can result in a value for αSE well above 90° (Fig. 1, left). For such high flip angles, far from the small-tip-angle regime[4], commonly-used sinc RF pulses produce degraded slice profiles, leading to a loss of signal and thus SNR, whereas RF pulses designed with Shinnar-Le Roux (SLR) methods promise superior performance[5].The goals of this study were therefore (1) to assess the benefits of SLR over sinc pulses for short-TR SE acquisitions, using both simulated and experimentally-measured slice profiles, (2) to consider the impact of B1+ inhomogeneity (especially problematic at ultra-high fields) and, as one of many anticipated applications of these SLR pulses, (3) to measure the cardiac component of physiological noise in 7T SE-EPI scans with a TR short enough to satisfy the Nyquist criterion for cardiac frequencies at ~1 Hz. This could lead to better characterization of the temporal specificity of SE-fMRI, potentially augmenting its well-known advantage in spatial specificity over GE-fMRI.

Simulations and phantom scans at 3T: Methods and Results

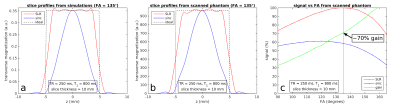

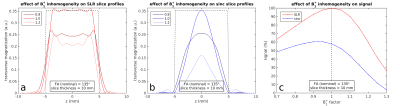

High-flip-angle excitation RF pulses, along with refocusing pulses, were designed in MATLAB using the SLR algorithm[5–7] with a bandwidth-time product of 8 (Fig. 1, right). Fig. 2a shows the corresponding steady-state slice profiles, obtained via Bloch simulations incorporating the effects of longitudinal relaxation. Slice profiles were measured experimentally at 3T (Siemens Trio) on an oil phantom (polydimethylsiloxane) that had a T1 of 800 ms; the resulting profiles (Fig. 2b) show good agreement with the simulated profiles. The excitation flip angle (FA) was varied from 90° to 165° (in 5° increments) and the net signal is plotted against FA in Fig. 2c, showing a ~70% gain for SLR over standard Hanning-windowed sinc pulses at the optimal FA.B1+ fields are spatially homogeneous in oil phantoms, unlike in human brains at 7T[8,9]. To assess the effect of B1+ inhomogeneity, we simulated slice profiles with varying factors applied to the RF pulse B1+ amplitudes; much higher signal is obtained from SLR over sinc pulses even when the “effective FAs” deviate from the target FAs for which the SLR pulses were designed (Fig. 3).

Human subjects at 7T: Methods and Results

Two healthy volunteers (2F, ages 26–33), having given informed consent, were scanned on a Siemens 7T whole-body scanner using a custom-built 31-channel head receive coil and birdcage transmit coil, with no tasks performed by the subjects.Using the SLR pulses described above, but with pulse duration increased from 8 to 14.5 ms to avoid RF clipping and SAR issues, single-shot single-slice SE-EPI data were acquired with the following parameters: TR/TE = 300/57 ms, BW = 1776 Hz/px (echo spacing = 0.65 ms), voxel size = 1.5×1.5×1.5 mm3 (FOV = 192×192 mm2, matrix = 128×128) and in-plane GRAPPA factor = 2. The excitation FA was varied from 90° to 165° (in 5° increments) for short runs of ~100 repetitions (~30 s) in order to empirically determine the FA that maximized signal in primary visual and sensorimotor cortical areas. The optimal FA, found to be 130° in both subjects, was then used in longer runs of 1000 repetitions (5 minutes). GE-EPI data were also acquired with almost all parameters matched to the SE-EPI scans, other than a 26 ms TE and a 50° FA sinc-pulse excitation. Little-to-no evidence for head movement was seen for either subject, based on visual inspection of the EPI data.

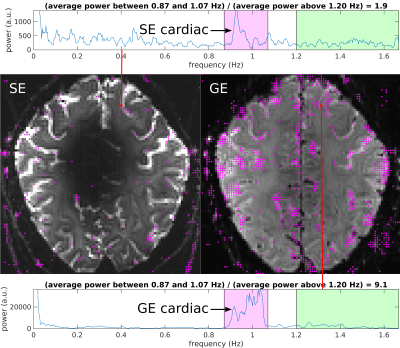

The power spectrum for each EPI voxel was estimated from its time series (sampling interval = TR = 0.3 s; Nyquist limit = 1.67 Hz) using the Thomson multitaper function “pmtm” in MATLAB. Fig. 4 shows the power spectrum from a voxel in Subject 1's SE-EPI data and from the corresponding GE-EPI voxel. These and all other voxels containing substantial power in the cardiac frequency band around 1 Hz are marked with purple dots in the images, showing far fewer “cardiac voxels” in the SE- versus GE-EPI data. Similar results were obtained in Subject 2 (Fig. 5). (Note that the signal loss in the center of the brain in the SE-EPI data—due to severe “overflipping”—was seen with both SLR and sinc pulses and does not impact the targeted cortical areas.)

Discussion

We have shown here that SLR pulses provide much higher SNR than sinc pulses for short-TR SE acquisitions, even when there is substantial B1+ inhomogeneity. As one application, we used SLR pulses and a TR of 300 ms in SE-EPI acquisitions at 7T, enabling the “direct” measurement of cardiac frequencies at ~1 Hz without aliasing. Our results support prior “indirect” measurements (using long TRs and pulse-oximeter cardiac recordings) showing substantially lower cardiac fluctuation in 7T SE- versus GE-EPI data[10]. Reduced cardiac fluctuation has also been reported at 3T for short-TR SE- versus GE-EPI data[11]; however, increased intravascular contributions to SE-fMRI signals at lower field strengths preclude a direct comparison with 7T results. Using a TR of 300 ms limited us to single-slice acquisitions because of SAR restrictions—understanding the impact of blood/CSF inflow on our results will require further investigation.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kyle Droppa for his assistance with volunteer recruitment and data acquisition and Tim Reese for pulse sequence development support. This work was supported by NIH grants P41-EB030006, U01-EB025162, R01-AT011429, R01-EB019437, R01-MH111419 and R01-EB016695, as well as by CIHR grant MFE-164755 and NSERC grant RGPIN-2022-04886, and was made possible by the resources provided by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10-RR019371.References

[1] Elster AD, Provost TJ. Large-tip-angle spin-echo imaging. Theory and applications. Investigative Radiology. 1993;28(10):944-53.

[2] DiIorio G, Brown JJ, Borrello JA, Perman WH, Shu HH. Large angle spin-echo imaging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1995;13(1):39-44.

[3] Ma J, Wehrli FW, Song HK. Fast 3D large‐angle spin‐echo imaging (3D FLASE). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1996;35(6):903-10.

[4] Pauly J, Nishimura D, Macovski A. A k-space analysis of small-tip-angle excitation. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1989;81(1):43-56.

[5] Pauly J, Le Roux P, Nishimura D, Macovski A. Parameter relations for the Shinnar-Le Roux selective excitation pulse design algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1991;10(1):53-65.

[6] Liao C, Stockmann J, Tian Q, Bilgic B, Arango NS, Manhard MK, Huang SY, Grissom WA, Wald LL, Setsompop K. High‐fidelity, high‐isotropic‐resolution diffusion imaging through gSlider acquisition with B1+ and T1 corrections and integrated ΔB0/Rx shim array. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2020;83(1):56-67.

[7] Berman AJL, Grissom WA, Witzel T, Nasr S, Park DJ, Setsompop K, Polimeni JR. Ultra‐high spatial resolution BOLD fMRI in humans using combined segmented‐accelerated VFA‐FLEET with a recursive RF pulse design. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2021;85(1):120-39.

[8] Collins CM, Smith MB. Signal‐to‐noise ratio and absorbed power as functions of main magnetic field strength, and definition of “90°” RF pulse for the head in the birdcage coil. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;45(4):684-91.

[9] Vaughan JT, Garwood M, Collins CM, Liu W, DelaBarre L, Adriany G, Andersen P, Merkle H, Goebel R, Smith MB, Ugurbil K. 7T vs. 4T: RF power, homogeneity, and signal‐to‐noise comparison in head images. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;46(1):24-30.

[10] Yacoub E, Van De Moortele PF, Shmuel A, Uğurbil K. Signal and noise characteristics of Hahn SE and GE BOLD fMRI at 7 T in humans. NeuroImage. 2005;24(3):738-50.

[11] Khatamian YB, Golestani AM, Ragot DM, Chen JJ. Spin-echo resting-state functional connectivity in high-susceptibility regions: accuracy, reliability, and the impact of physiological noise. Brain Connectivity. 2016;6(4):283-97.

Figures