3620

Unsupervised Susceptibility Artifact Correction in DTI Using a Deep Learning Forward-Distortion Model1Deparment of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 2National Magnetic Resonance Research Center (UMRAM), Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 3Neuroscience Graduate Program, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Susceptibility, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Brain, Artifacts

Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) requires correction of susceptibility artifacts before conducting quantitative analyses. Correction is typically performed by acquiring DWI images in reversed phase-encode directions, which are used to estimate and correct for the effects of susceptibility-induced field. In this work, we propose a Forward-Distortion Network (FD-Net) for correcting susceptibility artifacts at multiple b-values. We evaluate the quality of the corrected DWI images and Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) metrics, using FSL’s TOPUP as a reference classical method. In addition to rapid execution times, FD-Net exhibits high-fidelity performance for both DWI images and DTI metrics.

Introduction

Echo planar imaging (EPI) is the predominant sequence employed for diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), owing to its ability to quickly acquire k-space data1. However, EPI images are corrupted with susceptibility artifacts2 that must be corrected for accuracy of quantitative analyses3. A common solution is to perform correction via images acquired in reversed phase-encode (PE) directions to estimate the underlying susceptibility-induced displacement field4.In this work, we propose a Forward-Distortion Network (FD-Net)5 for the correction of DWI images from multiple b-values. We evaluate the quality of the corrected DWI images and extracted diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics6, namely fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD). In these evaluations, FSL’s classical TOPUP method is taken as a reference. We show the efficacy of FD-Net in correcting susceptibility artifacts in DWI images, and deriving high-quality FA and MD maps from corrected images.

Methods

Classical Correction ApproachField-map based susceptibility artifact correction techniques assume that distortions appear in opposite directions in reversed-PE images and consider only displacement along the PE direction7. In this classical approach, the estimated field is used to directly correct the reversed PE image pairs. Field-map based techniques have been shown to surpass registration-based/measured-field techniques8. In this work, we take as a “reference” method FSL’s TOPUP4, often considered a gold-standard for distortion correction in EPI. TOPUP uses the reversed-PE images to estimate the field9, using it in turn to apply correction.

Deep Learning Forward-Distortion Approach

We propose an unsupervised forward-distortion model, FD-Net5, for correcting susceptibility artifacts in DWI images from multiple b-values. FD-Net takes as input two reversed PE images and estimates both a displacement field and a corrected image5. The corrected image is then forward distorted in both PE directions using the estimated displacement field, to enforce consistency to the distorted input images. Figure 1a outlines the FD-Net architecture and Fig. 1b shows the details of the forward-distortion module.

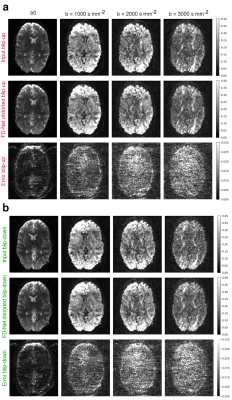

Here, a two-step training approach was employed: FD-Net was first trained on b0 DWI images, which have considerably higher SNR than b>0 images. Once a convergent network was trained on b0 images, FD-Net was fine-tuned on b>0 images. Examples of FD-Net’s forward-distorted images for multiple b-values are provided in Fig. 2.

Dataset and Learning Procedures

We used randomly selected unprocessed DWI images of 20 subjects from Human Connectome Project's 1200 Subjects Data Release10. The gradient tables include ~90 diffusion-weighting directions with 6 interspersed b0 acquisitions. The diffusion-weighting directions were uniformly distributed over three q-space shells with b=1000, 2000, and 3000 s mm-2, having roughly equal numbers of acquisitions on each shell.

Twelve subjects were used for training and eight for testing. For each training subject, all available volumes (with differing b-values and b-vectors) were utilized. Each volume consisted of 111 slices with a 168x144 image matrix . TOPUP correction was applied for reference. To compute FA and MD on the results of both TOPUP and FD-Net, we used DiPy’s11 DTI tensor model and related subroutines.

FD-Net was implemented in Tensorflow/Keras and was trained and fine-tuned using Adam optimizer for 100 epochs. Correction of a volume took on average ~7.5 seconds (~12 minutes in total per subject). In contrast, TOPUP took ~51 minutes to predict the field and an additional ~6 seconds to apply correction for each subject.

Results

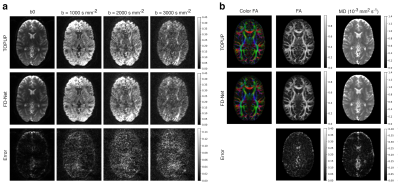

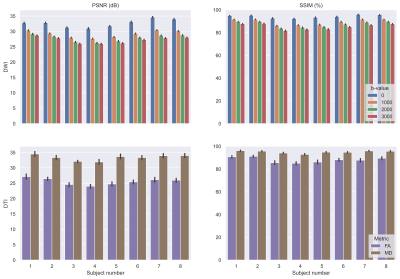

Visual comparison of FD-Net’s correction results for all b-values is provided in Fig. 3a, together with the TOPUP results. FD-Net provides similar performance to TOPUP in terms of DWI images. As DTI metrics, FA, MD, and color FA maps were computed based on FD-Net and TOPUP as shown in Fig. 3b. Visually, FD-Net provides similar overall performance to TOPUP.Figure 4 shows a comprehensive comparison for DWI images and DTI metrics across individual subjects in terms of peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index (SSIM). For these comparisons, images were masked using a median Otsu’s threshold over TOPUP’s corrected b0 images. An immediate observation is that FD-Net has comparable performance across different b-values for b>0 DWI images, while b0 images display improved performance due to their high SNR. The quality of FA and MD maps are also consistent across subjects.

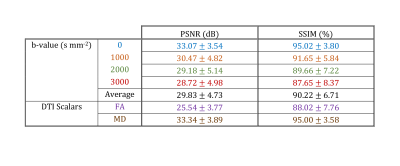

The table in Fig. 5 summarizes the average statistics for image quality assessment using PSNR and SSIM. FD-Net performs the best over b0 images, with performance over b>0 images being slightly reduced but consistent. For DTI metrics, FD-Net displays improved performance for MD when compared to that for FA, potentially due to MD being a low-dimensional diffusion metric.

Conclusion

The proposed FD-Net provides results comparable to TOPUP, both in terms of DWI images at various b-values and DTI metrics. Our unsupervised deep learning approach provides rapid correction of susceptibility artifacts, while maintaining high performance in subsequent quantitative analyses. The two-step training approach helps boost PSNR/SSIM and improve generalizability of the architecture. Our results indicate that the forward-distortion model is able to constrain fidelity by enforcing consistency to measurement data.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) via Grant 117E116. Data were provided by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 NIH Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research; and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University.

References

- S. J. Holdsworth and R. Bammer, “Magnetic resonance imaging techniques: fMRI, DWI, and PWI,” Semin. Neurol., vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 395–406, 2008.

- P. Mansfield, “Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes,” J. phys., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. L55–L58, 1977.

- J.-D. Tournier, S. Mori, and A. Leemans, “Diffusion tensor imaging and beyond: Diffusion Tensor Imaging and Beyond,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 1532–1556, 2011.

- S. M. Smith et al., “Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL,” Neuroimage, vol. 23 Suppl 1, pp. S208-19, 2004.

- A. Zaid Alkilani, T. Çukur, and E. U. Saritas, “A Deep Forward-Distortion Model for Unsupervised Correction of Susceptibility Artifacts in EPI”, Proc. of the 30th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, London, UK, p. 959, May 2022.

- D. Le Bihan et al., “Diffusion tensor imaging: concepts and applications,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 534–546, 2001.

- D. Holland, J. M. Kuperman, and A. M. Dale, “Efficient correction of inhomogeneous static magnetic field-induced distortion in Echo Planar Imaging,” Neuroimage, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 175–183, 2010.

- M. S. Graham, I. Drobnjak, M. Jenkinson, and H. Zhang, “Quantitative assessment of the susceptibility artefact and its interaction with motion in diffusion MRI,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 10, p. e0185647, 2017.

- J. L. R. Andersson, S. Skare, and J. Ashburner, “How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging,” Neuroimage, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 870–888, 2003.

- D. C. Van Essen, S. M. Smith, D. M. Barch, T. E. J. Behrens, E. Yacoub, and K. Ugurbil, “The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: An overview,” Neuroimage, vol. 80, pp. 62–79, 2013.

- E. Garyfallidis et al., “Dipy, a library for the analysis of diffusion MRI data,” Front. Neuroinform., vol. 8, p. 8, 2014.

Figures

Figure 1. (a) The proposed Forward-Distortion Network (FD-Net). (b) Detailed view of the forward-distortion module.

Figure 2. FD-Net forward-distorted images vs. the input blip-up/-down images for different b-values; left to right: increasing b-value from b0 (b=0) to b=3000 s mm-2. (a) Input blip-up image, FD-Net distorted blip-up image, and the error map between the two. (b) Input blip-down image, FD-Net distorted blip-down image, and the error map between the two. The display windows were adjusted for improved visibility of the details in the images.

Figure 3. (a) FD-Net correction results for different b-values; left to right: increasing b-value from b0 (b=0) to b=3000 s mm-2. (b) FD-Net results for DTI metrics; left to right: color FA, FA, and MD. All images were masked using a median Otsu’s threshold over the TOPUP corrected b0 images. 1st row: TOPUP results; 2nd row: FD-Net results; 3rd row: error map between FD-Net and TOPUP results. TOPOP results were used as reference. The display window were adjusted for improved visibility of the details in the images.

Figure 4. Performance for FD-Net in individual test subjects shown as average PSNR/SSIM values across volumes/slices for each different b-value and across slices for FA/MD. The error bars show the 95% confidence interval. 1st row: results for DWI images; 2nd row: results for DTI metrics. 1st column: PSNR in dB; 2nd column: SSIM as a percentage. All images were masked using a median Otsu’s threshold over the TOPUP corrected b0 images. TOPUP results were used as reference.

Figure 5. FD-Net performance metrics reported as mean ± standard deviation across test subjects, with respect to TOPUP. PSNR is reported in dB and SSIM as a percentage. Each b-value is averaged separately to delineate performance, and a total average over all b-values is provided in summary. FA and MD results are provided to assess the performance for DTI metrics. All images were masked using a median Otsu’s threshold over the TOPUP corrected b0 images.