3618

Evaluation of the impact of protocol settings on the variability of model estimations in multicenter diffusion MRI studies1Research Center for Healthcare Data Science, Zhejiang Lab, Hangzhou, China, 2College of Biomedical Engineering and Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 3Department of Imaging Sciences, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, United States, 4Center for Brain Imaging Science and Technology, College of Biomedical Engineering and Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 5School of physics, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, multicenter

A multicenter diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) study was designed with different b-table schemes, non-diffusion b0 number, and varied echo time (TE) in two 3T scanners of different vendors. Global sensitivity analysis of 6 traveling subjects was conducted to evaluate the impact of imaging protocol setting on the observed cross-scan variability of diffusion metrics.Introduction

Different diffusion protocols could change the scale and precision of quantitative diffusion measures1-3. For diffusion imaging in the multicenter projects, inconsistency of protocol across multiple scanner types is inevitable. Therefore, the multicenter variations come from varied acquisition parameters, system bias of scanners, and biological factor from different subject groups4,5. In this work, datasets from single-center and multicenter were acquired to evaluate the variations from protocol and scanner on diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI), neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) models and fiber tractography. Several key parameters in the diffusion acquisition like echo times (TE), b-table and non-diffusion b0 number were investigated. Global sensitivity analysis was later performed to highlight the dominant acquisition parameter that affects the diffusion metric in different brain regions.Methods

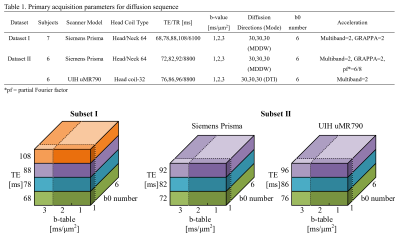

Two datasets were acquired at multiple TE using multi-shell schemes, then the data were rearranged to generate several subsets. Dataset I was acquired from 7 healthy subjects on a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner using the SE-EPI diffusion sequence with fixed diffusion time and duration, and Dataset II was acquired from 6 traveling subjects on 3T Siemens Prisma and UIH uMR790 using the clinical diffusion sequence. The two datasets were acquired using similar TEs, the same b-values, direction number, and the same b0 number. Other parameters were optimized to achieve similar total scan time and image quality at an isotropic voxel size of 2.5 mm. The main diffusion parameters are summarized in Table 1. The raw images were preprocessed using the same pipeline including denoising6, Gibbs-ring removal7, distortion and eddy current correction8 provided by MRtrix3 and FSL toolbox. Several DWI subsets were then extracted from each multi-TE data with single TE, reduced b-table scheme, and fewer b0 number as shown in Figure 1. Therefore, 16 subsets and 12x2 subsets were generated from Dataset I and II, respectively, and are denoted by Subset I and Subset II.All the DWI subsets were processed with the DKI, NODDI model fitting and tractography to obtain multiple microstructural features. The DKI metrics were fitted using the DESIGNER scripts9, the NODDI model was optimized using the AMICO method10, and the track density (TD) was calculated from the multi-shell global tractography using MRtrix311. Subsequently, all of these diffusion metric maps were non-linearly registered to the ICBM152 template, where the deep white matter (WM)12, subcortical regions and grey matter (GM) had been labeled.

Afterwards, the variations of diffusion metrics were analyzed. Firstly, the protocol- and scanner-related variations were compared between Subset I and II using the one-way ANOVA. Secondly, the protocol-related variations caused by a single acquisition parameter were evaluated by the coefficient of variance (CV) respectively among different TEs, b-tables and b0 numbers in Subset I. Finally, the CV and the Sobol’s global sensitivity analysis13 were performed in Subset II. The three acquisition parameters were comprehensively analyzed together with the scanner- and subject-related factors. Using the Saltelli method14, five factors were quasi-randomly sampled in a hypercube space to estimate the total sensitivity index for each diffusion metric.

Results

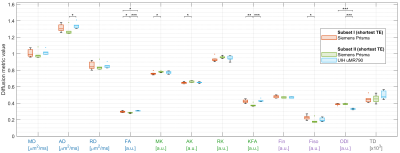

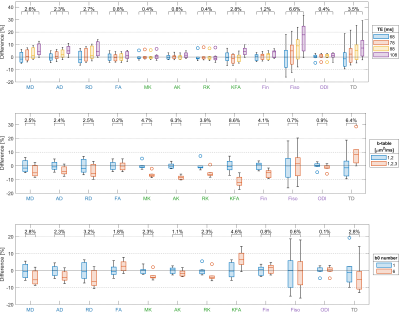

Figure 2 shows the diffusion metrics calculated from the subset data of the shortest TE in Subset I and II. The one-way ANOVA also shows a significant difference between those scans.Figure 3 shows the diffusion metrics derived from subsets with different TEs, b-tables and b0 numbers respectively in Subset I. The CVs among those specific subsets within WM were calculated and averaged among subjects.

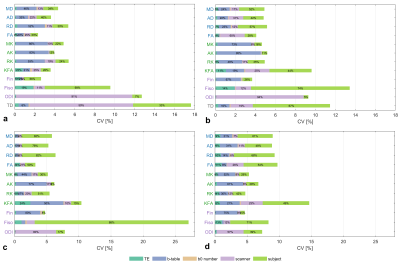

For each diffusion metric in Subset II, the CV among all the subsets and the total sensitivity indices of five factors are jointly shown in Figure 4. The results from different tissues were presented, and the TD is only calculated within WM in Figure 4ab.

Discussion

From the single center results in Figure 3, the measurement variation caused by individual acquisition parameters was confirmed with previous studies15-17, in which the RD, Fin and Fiso were TE dependent. Other metrics like KFA and TD also showed the dependency on TE, but the FA and MK were minimally affected. Comparing the two-shell and three-shell acquisitions, the high-order kurtosis metrics were generally changed more than the tensor metrics. It was also obvious in the TD, the tractography could capture more crossing-fibers from higher b-value acquisition18. The b0 number influenced the DTI and DKI models greater than the NODDI model.By comprehensively comparing these acquisition parameters in the global sensitivity analysis, we found the b-table was dominant to TD, diffusivity, and kurtosis metrics within both WM and GM. The NODDI model showed regional-specific properties, Fin was mainly affected by TE in the deep WM, and was more affected by the b-table in other brain regions. For Fiso, the dominant parameter was TE in WM, and was b-table in GM.

The multicenter dataset acquired using multiple protocols on traveling subjects helped to eliminate the subject-related variation and evaluate the contribution from protocol and scanner. From the global sensitivity analysis in Figure 4, the directional FA, KFA, ODI were found to be highly sensitive to the scanner, where the distribution of diffusion directions may matter.

Conclusion

In the multicenter diffusion acquisition, the b-table and TE were dominant parameters to most diffusion metrics, and their effects were regional-specific across the whole brain.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [2020TQ0296,2021M692961], National Natural Science Foundation of China [82102139], National Key Research and Development Program of China [2022ZD0211500], Key Research Project of Zhejiang Lab [No. 2022ND0AC01], Open Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning.References

1. McKinnon E T, Jensen J H, Glenn G R, et al. Dependence on B-Value of the Direction-Averaged Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Signal in Brain. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2017, 36: 121–127.

2. Huang S Y, Nummenmaa A, Witzel T, et al. The Impact of Gradient Strength on in Vivo Diffusion MRI Estimates of Axon Diameter. NeuroImage, 2015, 106: 464–472.

3. Aja-Fernández S, Pieciak T, Tristán-Vega A, et al. Scalar Diffusion-MRI Measures Invariant to Acquisition Parameters: A First Step towards Imaging Biomarkers. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2018, 54: 194–213.

4. Zhu A H, Moyer D C, Nir T M, et al. Challenges and Opportunities in DMRI Data Harmonization. Bonet-Carne E, Grussu F, Ning L, et al. Computational Diffusion MRI. 2019: 157–172.

5. Zhu T, Hu R, Qiu X, et al. Quantification of Accuracy and Precision of Multi-Center DTI Measurements: A Diffusion Phantom and Human Brain Study. NeuroImage, 2011, 56(3): 1398–1411.

6. Veraart J, Novikov D S, Christiaens D, et al. Denoising of Diffusion MRI Using Random Matrix Theory. NeuroImage, 2016, 142: 394–406.

7. Kellner E, Dhital B, Kiselev V G, et al. Gibbs-Ringing Artifact Removal Based on Local Subvoxel-Shifts: Gibbs-Ringing Artifact Removal. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2016, 76(5): 1574–1581.

8. Andersson J L R, Sotiropoulos S N. An Integrated Approach to Correction for Off-Resonance Effects and Subject Movement in Diffusion MR Imaging. NeuroImage, 2016, 125: 1063–1078.

9. Ades-Aron B, Veraart J, Kochunov P, et al. Evaluation of the Accuracy and Precision of the Diffusion Parameter EStImation with Gibbs and NoisE Removal Pipeline. NeuroImage, 2018, 183: 532–543.

10. Daducci A, Canales-Rodríguez E J, Zhang H, et al. Accelerated Microstructure Imaging via Convex Optimization (AMICO) from Diffusion MRI Data. NeuroImage, 2015, 105: 32–44.

11. Smith R E, Tournier J-D, Calamante F, et al. Anatomically-Constrained Tractography: Improved Diffusion MRI Streamlines Tractography through Effective Use of Anatomical Information. NeuroImage, 2012, 62(3): 1924–1938.

12. Mori S, Oishi K, Jiang H, et al. Stereotaxic White Matter Atlas Based on Diffusion Tensor Imaging in an ICBM Template. NeuroImage, 2008, 40(2): 570–582.

13. Sobol′ I M. Global Sensitivity Indices for Nonlinear Mathematical Models and Their Monte Carlo Estimates. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 2001, 55(1): 271–280.

14. Saltelli A. Making Best Use of Model Evaluations to Compute Sensitivity Indices. Computer Physics Communications, 2002, 145(2): 280–297.

15. Veraart J, Novikov D S, Fieremans E. TE Dependent Diffusion Imaging (TEdDI) Distinguishes between Compartmental T2 Relaxation Times. NeuroImage, 2018, 182: 360–369.

16. Lin M, He H, Tong Q, et al. Effect of Myelin Water Exchange on DTI‐derived Parameters in Diffusion MRI: Elucidation of TE Dependence. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2018, 79(3): 1650–1660.

17. Gong T, Tong Q, He H, et al. MTE-NODDI: Multi-TE NODDI for Disentangling Non-T2-Weighted Signal Fractions from Compartment-Specific T2 Relaxation Times. Neuroimage, 2020, 217: 116906.

18. Fan Q, Nummenmaa A, Witzel T, et al. Investigating the Capability to Resolve Complex White Matter Structures with High b -Value Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging on the MGH-USC Connectom Scanner. Brain Connectivity, 2014, 4(9): 718–726.

Figures

Figure 1.

Data description. Table 1 lists the main acquisition parameters of Dataset I and II. The bottom figure depicts the under-sampled subsets. For each single TE scan, four subsets were extracted: two-shell with one b0 volume, two-shell with six b0 volumes, three-shell with one b0 volume, and three-shell with six b0 volumes.

Figure 2.

The diffusion metric values within whole white matter of three scans from Subset I and II. Each box shows the median, the lower and upper quartiles of all subjects for each scan, and is grouped by colors. The stars above each two scans denote the significance of ANOVA.

Figure 3.

The relative difference of diffusion metric values among different scans from Subset I. The upper, middle, and bottom rows show the data of different TEs, b-tables and b0 number, respectively. Each box shows the median, the lower and upper quartiles of the metrics within whole white matter from 7 subjects, and the mean values of blue boxes are normalized to 0. The CVs among scans are shown above the boxes, and the values were averaged among the subjects.

Figure 4.

The global sensitivity indices weighted by CV within a) deep white matter regions, b) whole white matter, c) subcortical region and d) whole grey matter in subset II. The bar length indicates the CV among all subsets. The colors and percentages within bars indicate the total sensitivity indices of the five relevant factors, and percentages less than 5% and lower than the 95% confidence interval are neglected.