3601

A general framework for analyzing the various contributions to reproducibility in brain morphometry1Laboratory on Quantitative Medical Imaging, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 2Henry Jackson Foundation for Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD, United States, 3Rehabilitation Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Segmentation, Software Tools

We propose a framework for differentiating the contributions to the reproducibility in brain morphometry from the true inter-individual differences, experimental procedures, and data-processing methods. As an application, we build a linear mixed-effect model to evaluate and compare two segmentation software tools, Freesurfer and vol2Brain, in their reproducibility in measuring volumes of 32 regions of interest. For both software and for most structures under study, our approach successfully reveals the dominance of inter-subject variability over noise. Vol2Brain introduces less noise than Freesurfer for all subcortical nuclei while Freesurfer shows better performance for gray matter, cortex, cerebral white matter, and cerebellum cortex.Introduction

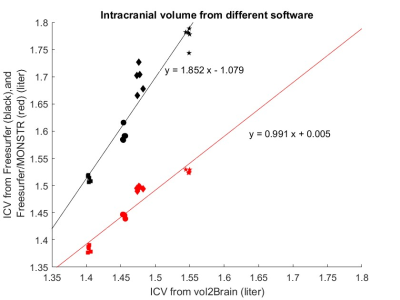

Brain morphometry is useful to assess the normal development of human brain and is a good indicator of brain disorders. In particular, the volumes of brain structures can be measured from MRI using segmentation software. We are interested in the true biological variability, which is, however, often confounded by other sources of noise from both MRI experiments and processing software. Little information was available in the literature on the relative importance of these noise sources. For example, previous studies on reproducibility were based on datasets with either one subject and one software 1, or only 2 repeated scans for each subject 2-5. To this end, we propose a general framework to separate the biological, experimental, and processing-related contributions to reproducibility. Given sufficient and proper data, this framework would enable us to measure the true inter-subject variability and estimate the contributions to noise from segmentation software and the experimental factors, e.g., data acquisition, scanners, and pulse sequences. Then we apply this framework to a dataset of 4 subjects with 5 repeated scans on a Siemens Prisma 3T scanner, to evaluate and compare the reproducibility of two segmentation software, Freesurfer (version 6.0.0) 6 and vol2Brain (version 1.0) 7.To measure inter-subject variability, we should properly deal with systematic confounding factors. Inter-individual variations in brain volumetry can be noticeably accounted for by their brain sizes fixed at a young age, which can be effectively quantified by the total intracranial volume (ICV) 8. The ICV was measured using T1-weighted images in Freesurfer. However, this can be improved by using a brain mask that combines information from both T1- and T2-weighted images. The software, MONSTR 9, automates this process and generates a brain mask, which can be utilized by Freesurfer in their succeeding steps. Therefore, in this study, we perform the reproducibility analysis on volumes normalized by the ICV, with and without implementing MONSTR’s mask in the Freesurfer pipeline.

Methods

We used a linear mixed-effect (LME) model to analyze the variability in the measurements. For the volume of each ROI reported from each software, we model it as the sum of three terms:$$V_{ij} = V_0 + a_i + e_{ij} \tag*{Equation (1)}$$

where subscripts i = 1, 2, 3, 4 and j = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 are for 4 subjects and 5 replicated scans, respectively. Vij represents a volume measurement of an ROI, normalized by the ICV. V0 is a constant fixed effect, representing the mean normalized volume across all replicates of all subjects. $$$a$$$i is a random effect, representing the variation of the normalized volume between subjects. eij is a random effect, representing the residual noise, which comes both from the experiment and segmentation. Note that we built an LME model separately for each ROI for each software.

We used the coefficients of variation as measures of inter-subject variability and noise, i.e.,

$$\text{Inter-subject variability} = \sigma_a/V_0 \tag*{Equation (2)}$$

$$\text{Noise} = \sigma_e/V_0 \tag*{Equation (3)}$$

where $$$\sigma_a$$$ and $$$\sigma_e$$$ are the standard deviations of $$$a$$$i and eij in Equation (1), respectively.

Results

- Brain mask

As shown in Figure 1, Freesurfer produces an ICV about 10% larger than vol2Brain. However, with the improved brain mask from MONSTR, the ICVs from Freesurfer and vol2Brain match well. Furthermore, MONSTR significantly reduces the intra-subject variability, to values comparable to that from vol2Brain. - Systematic differences between software

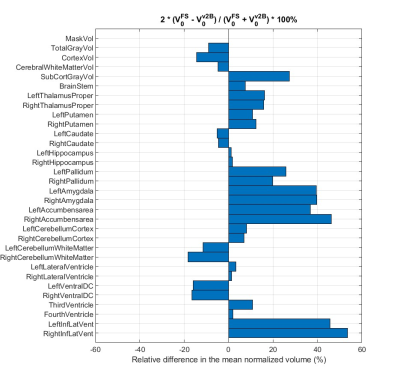

As shown in Figure 2, there is a systematic disagreement up to 53%, in the mean normalized volumes of all ROIs between Freesurfer and vol2Brain. However, the direction of the difference is consistent bilaterally. This suggests that the cause of the systematic disagreement between software is the underlying segmentation methodology rather than noise. - Inter-subject variability

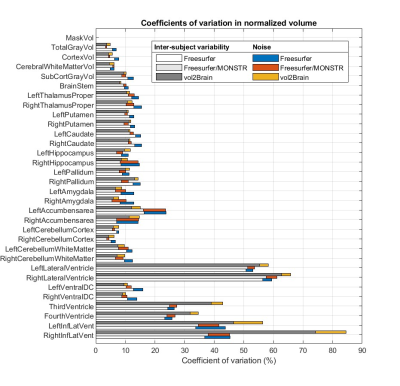

As shown in Figure 3, the inter-subject variability dominates over noise for most ROIs, indicating good performance by both software. The exception is the right accumbens area, where Freesurfer reports a noise roughly equal to the inter-subject variability, whereas in vol2Brain noise remains subdominant. - Noise

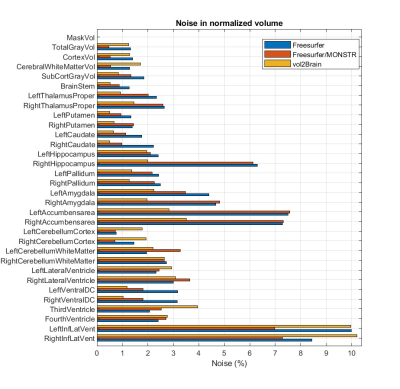

As shown in Figure 4, MONSTR’s brain mask significantly reduces the noise in Freesurfer’s measurements of normalized volumes of most ROIs, except the right putamen, right amygdala, accumbens area, left cerebellum white matter, lateral ventricle, and third and fourth ventricles.

We also observe that vol2Brain produces a smaller noise for all subcortical nuclei, whereas Freesurfer shows much better performance for gray matter, cortex, cerebral white matter, and cerebellum cortex.

Discussion

Our dataset includes only 4 subjects, which makes it difficult to obtain the underlying true biological variability, as implied by the different values of inter-subject variability from different software in Figure 3. In a future study, we will address this problem by extending our analysis to a dataset with more subjects.Conclusion

We proposed a framework for analyzing the reproducibility of brain morphometry and used it to assess the performance of Freesurfer and vol2Brain. Vol2Brain shows better reproducibility in subcortical nuclei, while Freesurfer outperforms vol2Brain in gray matter, cortex, cerebral white matter, and cerebellum cortex. Replacing Freesurfer’s brain mask with that from MONSTR helps reduce the noise in the normalized volumes for most ROIs under study.Acknowledgements

RD is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship of the National Institutes of Health.References

[1] Hans-Jürgen Huppertz et al., “Intra- and Interscanner Variability of Automated Voxel-Based Volumetry Based on a 3D Probabilistic Atlas of Human Cerebral Structures,” NeuroImage 49, no. 3 (February 1, 2010): 2216–2224, accessed July 25, 2022, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811909011379.

[2] José V. Manjón and Pierrick Coupé, “VolBrain: An Online MRI Brain Volumetry System,” Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 10 (2016), accessed July 20, 2022, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fninf.2016.00030.

[3] Robin Wolz et al., “Robustness of Automated Hippocampal Volumetry across Magnetic Resonance Field Strengths and Repeat Images,” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 10, no. 4 (2014): 430, accessed July 28, 2022, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.jalz.2013.09.014.

[4] Mandy Melissa Jane Wittens et al., “Inter- and Intra-Scanner Variability of Automated Brain Volumetry on Three Magnetic Resonance Imaging Systems in Alzheimer’s Disease and Controls,” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 13 (October 7, 2021): 746982, accessed July 25, 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8530224/.

[5] Enrica Cavedo et al., “Fully Automatic MRI-Based Hippocampus Volumetry Using FSL-FIRST: Intra-Scanner Test-Retest Stability, Inter-Field Strength Variability, and Performance as Enrichment Biomarker for Clinical Trials Using Prodromal Target Populations at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease,” Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 60, no. 1 (2017): 151–164.

[6] Bruce Fischl et al., “Whole Brain Segmentation: Automated Labeling of Neuroanatomical Structures in the Human Brain,” Neuron 33, no. 3 (January 31, 2002): 341–355, accessed July 20, 2022, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S089662730200569X.

[7] José V. Manjón et al., “Vol2Brain: A New Online Pipeline for Whole Brain MRI Analysis,” Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 16 (May 24, 2022): 862805, accessed September 29, 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9171328/.

[8] J. L. Whitwell et al., “Normalization of Cerebral Volumes by Use of Intracranial Volume: Implications for Longitudinal Quantitative MR Imaging,” AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology 22, no. 8 (September 2001): 1483–1489.

[9] Snehashis Roy et al., “Robust skull stripping using multiple MR image contrasts insensitive to pathology”, NeuroImage, Volume 146, 2017, 132-147.

Figures