3599

Tract-specific Evaluation of White Matter Hyperintensity Segmentation1Centre for Medical Image Computing and Department of Computer Science, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2AINOSTICS Ltd., Manchester, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Segmentation, Neuroinflammation, White Matter Hyperintensity Segmentation

We propose a tract-specific white matter hyperintensity (WMH) segmentation evaluation as a new way to assess WMH segmentation techniques. Currently, WMH segmentation is assessed globally or between periventricular and deep white matter (WM) regions, which has no obvious functional relevance. WM tracts have known functional relevance and associations to neurological conditions. We demonstrate that this new approach allows for functionally-relevant assessment of techniques. Two WMH segmentation techniques are compared to highlight the performance differences across a key tract associated with processing speed. We also found significant performance differences across this tract, which would be missed by standard evaluation methods.

Introduction

White matter hyperintensity (WMH) segmentation is important as WMH are linked with increased risk to several neurological conditions [1,2,3]. Multiple methods exist to segment WMH [4], but these methods need to be evaluated to determine which is the most appropriate. Currently WMH segmentation performance is only assessed globally [4] or within a ventricular distance threshold [5]. However, there is no obvious functional relevance gained from WMH identified in periventricular or deep white matter (WM) regions [6]. Additionally, these methods have varying definitions for periventricular WMH and arbitrary distance thresholds [7]. In contrast, WM tracts are anatomically defined regions with known functional relevance and associations to neurological conditions [8,9,10], making them attractive for categorising WMH lesions. Motivated by this observation, we propose a tract-specific evaluation framework to provide functionally-relevant evaluation of WMH segmentation techniques. This will allow for performance to be quantified across strategic tracts associated with "task-specific" impairments.Methods

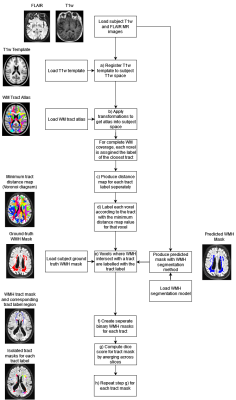

Tract-specific evaluation frameworkThe proposed framework takes MR images of a subject (T1w and FLAIR), the corresponding ground-truth WMH segmentation, and the WMH segmentation to be evaluated as inputs to produce performance metric reports across WM tracts (Figure 1). The framework is designed to avoid the need for diffusion MRI data which is not routinely available. The XTRACT atlas was used to provide the WM tract mappings [11].

First the XTRACT template T1w image [11] is registered to the subject T1w input using nearest neighbour interpolation. The transformations are stored and applied to the XTRACT atlas to align it with the subject MR images. To ensure complete WM coverage after registration, we assume white matter voxels outside any tract boundaries should be assigned to the nearest tract. This was achieved by computing a multi-channel distance map for each tract. Voxels were labelled by tract using this distance map to select the channel with the minimum distance value for each voxel.

Predicted and ground truth WMH masks for each tract were produced by selecting WMH voxels that intersected with each expanded atlas region. The intersection of each WMH mask and the expanded atlas was then computed to produce WMH masks for each tract. The dice score [12] was then computed for each WMH tract mask slice and averaged across the slices in (figure 1g &h).

Demonstration experiments

To demonstrate the framework, we compared two WMH segmentation methods. The baseline model was a re-implementation of the Sysu Media ensemble U-net [13], and the MPEU-net was an extension of the baseline, which was based of the TRUE-net [5]. We used public data from the MICCAI WMH segmentation challenge, which contained 60 subjects each with FLAIR, T1-w and manual ground-truth segmentations [4].

Results & Discussion

What is the added value of tract-specific evaluation when comparing two WMH segmentation techniques?Performance comparisons across tracts are useful, as users will likely want to select WMH segmentation techniques that perform well across tracts associated with a specific cognitive impairment. The relative tract performances of the different WMH segmentation techniques were compared across Superior Thalamic Radiation (STR), which is associated with information processing. Increased WMH volume on the STR has been shown to be correlated with a reduced information processing speed [8]. The tract-specific framework uncovered a statistically significant improvement in performance along the right side of the STR when using the MPEU-net in comparison to the baseline method. Across the right side of the STR, the dice score improved from (0.67 ±0.25) to (0.73 ± 0.25) with a p-value = 0.003. This demonstrated the added value of tract-specific evaluation, as this difference in performance would not be captured by a global or periventricular and deep white matter evaluation approach.

What is the added value of Tract-Specific Evaluation over periventricular and deep WM evaluation?

Segmentation performance variation between periventricular WMH (PWMH) and deep WMH (DWMH) has already been evaluated [5]. This is important because PWMH tend to be larger and have higher contrasts when compared to DWMH, which has been correlated with improved segmentation capabilities near ventricles [14]. There are features associated with a given tract's location and tract-specific evaluation may uncover performance variations that are not explained by PWMH and DWMH distributions.

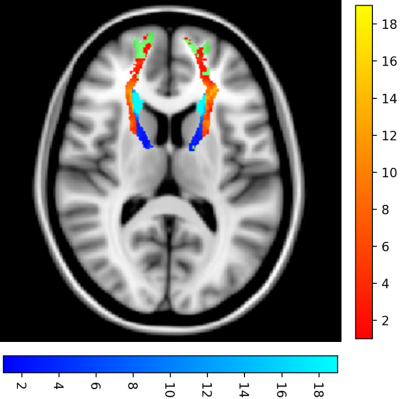

To demonstrate this, we investigated the anterior thalamic radiation (ATR) tract, which has been shown as a key WM tract for processing speed. Increased WMH volume on the ATR has been shown to be correlated with a reduced processing speed [15]. The ATR performed above the global average result for both methods. From figure 2, 68.3% of the ATR WMH voxels are classified as deep WMH. Given periventricular WMH are in the minority, WMH segmentation performance is likely influenced by other unique tract location-based features and not just the distance from the ventricles. This insight could not be captured by the standard global or periventricular and deep white matter evaluation methods.

Conclusion

The proposed evaluation framework provides a functionally-relevant method for measuring the performance variation across WM tracts. It allows for the relative performance of WMH segmentation techniques to be assessed tract-wise. Accurate evaluation of the performance variation across functionally-relevant regions, may lead to an improved understanding of a technique’s weaknesses that will ultimately inform the development of future technique.Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ainostics Ltd. for their support. Computing resources and support were provided by AINOSTICS Ltd., enabled through funding by Innovate UK. This work was supported by EPSRC grants EP/R513143/1 and EP/W524335/1.References

[1] B. Frey, et al., “Characterization of White Matter Hyperintensities in Large-Scale MRI- Studies”, Frontiers in Neurology, 2019, 10, 1664-2295.

[2] K. Misquitta K, et al., “Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. White matter hyperintensities and neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease”, Neuroimage Clin., 2020, 28, 102367.

[3] A. Butt, et al., “White matter hyperintensities in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis”, J Neurol Sci., 2021, 15:426, 117481.

[4] H. J. Kuijf et al., “Standardized Assessment of Automatic Segmentation of White Matter Hyperintensities and Results of the WMH Segmentation Challenge,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 2019, 38:11, 2556-2568.

[5] V. Sundaresan, et al., “Triplanar ensemble U-Net model for white matter hyperintensities segmentation on MR images”, Med Image Anal., 2021, 73, 102184

[6] C. DeCarli, et al., “Anatomical mapping of white matter hyperintensities (WMH): exploring the relationships between periventricular WMH, deep WMH, and total WMH burden”, Stroke, 2005, 36:1, 50-5.

[7] L. Griffanti, et al., “Classification and characterization of periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities on MRI: A study in older adults”, NeuroImage, 2017, 170, 174–181.

[8] L. Vergoossen, et al., “Interplay of White Matter Hyperintensities, Cerebral Networks, and Cognitive Function in an Adult Population: Diffusion-Tensor Imaging in the Maastricht Study”, Radiology, 2021, 298:2, 384-392.

[9] S. Seiler S, et al., “Cerebral tract integrity relates to white matter hyperintensities, cortex volume, and cognition”, Neurobiol Aging, 2018, 72, 14-22.

[10] B. Rizvi, et al., “Tract-defined regional white matter hyperintensities and memory”, Neuroimage Clin, 2020, 25, 102143.

[11] S. Warrington, et al., “XTRACT - Standardised protocols for automated tractography in the human and macaque brain” NeuroImage., 2020, 217, 1053-8119.

[12] F. Milletari, N. Navab and S. Ahmadi. “V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation” 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), 2016, 565-571

[13] H. Li, et al.,” Fully convolutional network ensembles for white matter hyperintensities segmentation in MR images” Neuroimage, 2018, 183, 650-665

[14] J. Chen, et al., “Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Bilateral Distance Partition of Periventricular and Deep White Matter Hyperintensities: Performance of the Method in the Aging Brain”, Acad Radiol, 2021, 28:12, 1699-1708.

[15] J. M. Biesbroek, et al., “SMART Study Group. Association between subcortical vascular lesion location and cognition: a voxel-based and tract-based lesion-symptom mapping study. The SMART-MR study.”, PLoS One, 2013, 8:4, 60541.

Figures