3585

Ultra rapid volumetric imaging for diagnosis in memory clinic: assessment of white matter hyperintensities quantification

Carole Helene Sudre1,2, Haroon R Chughtai2, David L Thomas3,4, David Cash4, Miguel Rosa-Grilo4, Millie Beament4, Frederik Barkhof2,4,5, Daniel Alexander2, Cath Mummery4, Nick Fox4, and Geoff JM Parker2

1MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for Medical Image Computing, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Brain Repair and Rehabilitation, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Department of Radiology & Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands

1MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for Medical Image Computing, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Brain Repair and Rehabilitation, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Department of Radiology & Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Segmentation, Dementia

Acquisition time is a crucial factor in the tolerability and availability of MRI examinations for patients attending memory clinics. The suitability of using prototype ultra-rapid sequences for the quantification of white matter hyperintensities was assessed by comparing segmentation outputs from standard clinical and ultra-rapid sequences. Despite a slightly lower sensitivity to smaller lesions, quantification of white matter hyperintensities when using ultra-rapid sequences was very highly correlated with lesion volumes obtained from standard sequences.Introduction

MRI is essential for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients attending memory clinics. Decreasing MRI acquisition time has multiple advantages, including a better tolerability for patients, reduced cost, increased availability, and reduced likelihood of poor image quality due to motion. The inability to remain still in the scanner is common in patients with dementia, and the resulting artefacts can negatively impact diagnosis accuracy and quantification of important biomarkers1. Ultra-rapid imaging has the potential to transform clinical practice by reducing scan times and improving patient experience and compliance. However, faster imaging inevitably involves compromise between acquisition speed and image quality (e.g. spatial resolution, signal-to-noise etc.). We investigate the possibility of using ultra-rapid imaging for the quantification of white matter hyperintensities (WMH), a hallmark of cerebral small vessel disease and a key biomarker routinely quantified for diagnosis purposes in individuals attending memory clinics.Methods

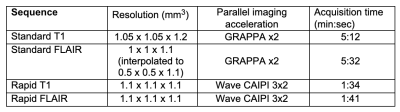

43 patients from a memory clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (London, UK) underwent brain imaging using both ultra-fast and standard clinical versions of 3D T1-weighted MPRAGE and T2-FLAIR sequences on a 3T Siemens Prisma. The study received ethical approval (London Hampstead REC 21/LO/0815) and all patients gave written informed consent. Rapid acquisitions were performed using Siemens Wave CAIPI work-in-progress (WIP) sequences. Table 1 summarises the main sequence parameters for the two types of acquisition. Scans from one individual were excluded due to motion artefacts. For each remaining subject, the two T1 sequences were affinely aligned to allow for direct comparison of the segmentation outputs using NiftyReg2. WMH were automatically segmented using either standard or rapidly acquired sequences using BaMoS3. Distributions of outlierness compared to healthy appearing white matter were compared using the Mahalanobis distance across the two outputs. Spearman correlation and intra-class correlation were used to assess the alignment of results in terms of overall volumes. Lesion maps were compared both in terms of semantic segmentation and instance segmentation tasks using dice score coefficient, normalised surface distance and detection F1 score4. Lesion instances were identified using 8-neighborhood. Characteristics of erroneous and correct detections were further compared by size.Results

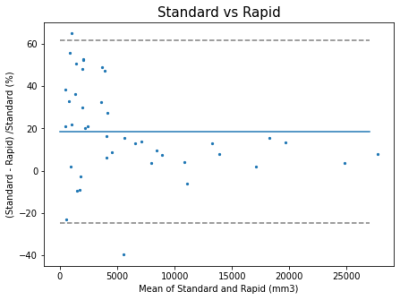

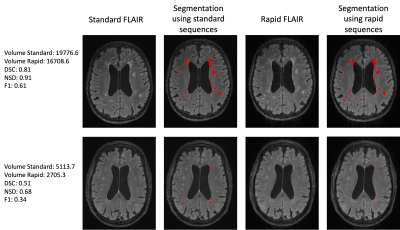

WMH volumes using standard or ultra-rapid sequences were highly correlated (rho=0.964 p<0.00005) with inter-class correlation of 0.94. Across all patients, segmented volumes using the standard clinical sequences varied from 509.28 to 28,862 mm3 with a median of 4360 mm3. WMH volumes appeared to be slightly underestimated using the ultra-rapid sequences with a median difference of 684.6 mm3 (IQR= [265.38;1225.23]) or a percentage difference of 14.6% [4.5; 32.6](Figure 1). When considering segmentation overlap in the context of a semantic segmentation task, the median dice score coefficient (DSC) reached 0.64 [0.47;0.75] and the normalised surface distance (NSD) was 0.79 [0.64;0.87]. In terms of lesion detection, the median F1 score was 0.42 [0.30;0.53]. 62% of the erroneous lesions were false negatives (i.e. missed on the ultra-rapid sequences) and generally much smaller (median 5 voxels [3;8]) than the correctly detected lesions (median 17 voxels [8;40]) (see Figure 2 for examples of segmentation comparisons). Among the correctly detected lesions, segmentations using the ultra-rapid sequences also yielded smaller volumes but with overall high overlap scores (DSC 0.65 [0.47;0.78]; NSD 0.94 [0.77;1.00]). In terms of signal intensity, the detected lesions were slightly less hyperintense in the ultra-rapid images (median Mahalanobis distance compared to healthy white matter 4.64 [3.69;5.79]) than in the standard images (4.88 [3.77;6.20]) (Figure 3).Discussion

The high correlation between quantified volumes of WMH when using standard and ultra-rapid sequences highlights the clinical utility of fast acquisitions when considering global volume of damage as diagnosis marker. The overall reduced outlierness, reduced sensitivity to smaller lesions and underestimation of the volume of larger lesions could all be explained by the slight increase in image blurring introduced in ultra-rapid sequences. Blurring could be reduced in future implementations by increasing resolution or applying super-resolution reconstruction techniques.Conclusion

Good quality 3D T1w and FLAIR images can be acquired in vastly reduced scan times using Wave CAIPI accelerated ultra-rapid scanning. WMH quantification using these ultra-rapid sequences appears to perform reasonably well in the context of dementia diagnosis. Further work is however required to better understand potential source of biases in the sensitivity of such sequences to damaged tissue (location, lesion pattern...) and to assess sensitivity to lesion change over timeAcknowledgements

This study has been funded by Biogen Idec UK. CHS is supported by Alzheimer's Society (AS-JF-17-011)References

1. Slipsager, J. M. et al. Quantifying the Financial Savings of Motion Correction in Brain MRI: A Model‐Based Estimate of the Costs Arising From Patient Head Motion and Potential Savings From Implementation of Motion Correction. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 52, 731–738 (2020).

2. Modat, M. et al. Global image registration using a symmetric block-matching approach. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 1, 2 (2014).

3. Sudre, C. H. et al. Bayesian Model Selection for Pathological Neuroimaging Data Applied to White Matter Lesion Segmentation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 34, (2015).

4. Maier-Hein, L. et al. Metrics reloaded: Pitfalls and recommendations for image analysis validation. (2022).

Figures

Details of the sequences acquired for the study comparing rapid and standard acquisitions

Bland-Altman plot comparing the quantified volumes of WMH when using the standard acquisition sequences and the ultra-rapid ones.

Example of segmentation (high and lower performance) using standard and ultra-rapid sequences

Comparison of histogram of outlierness for the standard and ultra-rapid sequences when compared to healthy appearing white matter

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/3585