3578

Myelin, Iron, and Free Water Content Quantification Through BIOPHYSICSS Deep Learning1Department of Neurology, Buffalo Neuroimaging Analysis Center, Buffalo, NY, United States, 2Department of Medical Engineering, Carinthia University of Applied Sciences, Klagenfurt, Austria, 3Department of Neuropathology and Neurochemistry, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 4Department of Computer Science and Automation, Technische Universität Ilmenau, Ilmenau, Germany, 5Department of Computer Science and Automation, Center for Biomedical Imaging, Clinical and Translational Science Institute at the University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Quantitative Imaging, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

Clinical translation of quantitative MRI (qMRI) is challenged by the multiple dependencies MR signal has on different tissue compartments. We previously introduced a neural network designed for single subject analysis (BIOPHYSICSS-DL) that overcomes the multiple tissue dependencies of qMRI and produces maps of source content. BIOPHYSICSS-DL has previously focused to myelin and iron quantification in the brain but in this work we expand that model to include a free water compartment. The network also used exclusively quantitative MRI metrics but the expansion of this model was accomplished with weighted MRI data which is another critical step to eventual clinical adoption.Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) quantities, such as relaxation rates, QSM, MTR, or Proton Density (PD), are sensitive to several biological tissue components including myelin, water, and iron, but none of them directly represents a single biological compartment of interest. The co-dependence on multiple biological compartments has been the major impediment to the widespread clinical adoption of quantitative MRI (qMRI). Neural networks are an ideal tool to invert the underlying relationship between biological tissue composition and MRI signal. We have recently introduced a self-calibrated deep-learning approach toward quantification of tissue iron and myelin from R1, R2*, and QSM: BIOquantification through PHYSIcs-Constrained Single-Subject Deep Learning (BIOPHYSICSS-DL).1The present work expands this approach toward estimating the free water content in addition to myelin and iron concentration maps, rendering the method more robust toward pathological alterations, e.g., due to inflammation-related edema. Our approach achieves water content quantification without additional scan time.

Methods

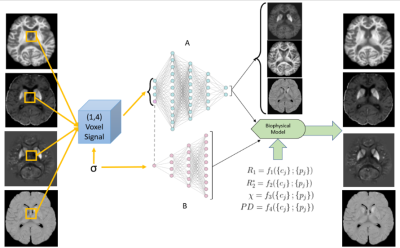

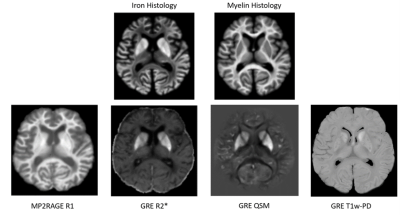

Neural Network Architecture: We utilized the previously introduced BIOBIOPHYSICSS-DL autoencoder network.1 This architecture can be trained on data from a single (N=1) multiparametric MRI exam without ground truth data for tissue content or model parameters. We expanded the input quantities toward including the T1-weighted proton density from multi-echo GRE (S0) and the source quantities toward including the free water content (Fig. 1).Ex Vivo Histology: We acquired R1, R2*, S0 (T1w-PD from R2* fit), and QSM in a cadaver head at 7T (Fig. 2). The extracted brain (three weeks at room temperature) was stained for iron and myelin using diaminobenzidine (DAB)-enhanced Turnbull blue and Luxol fast blue-periodic acid Schiff (LFB-PAS), respectively.2 qMRI maps were semi-automatically co-registered to the stains.

Signal Models: The BIOBIOPHYSICSS-DL decoder network includes predefined biophysical models that re-create the MRI signal quantities from the biological tissue component maps. Proper estimation of tissue content depends on sufficient input information (MRI measurements) as well as accurate biophysical models. In this work, we utilized generalized polynomial signal models. To properly account for T1-weighting in the S0 input image, the PD-related signal model utilized a cubic signal family that was found to be more effective than the quadratic-linear models that were used for the other qMRI metrics. Increasing water content was constrained to have a negative effect on R1 and R2* relaxation rates and no effect on susceptibility. The network was trained with an ADAM optimizer3 on a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPU.

Results

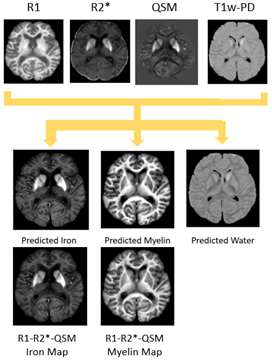

The network training converged after approximately 12 minutes or 5000 epochs. Iron and myelin predictions of ex vivo data demonstrated expected contrast in deep gray matter regions and parts of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 3), as was also observed without the inclusion of the free water component. In the case of the iron estimation, inclusion of water compartments improved estimation in the subcortical WM compared to the stains. In the case of the myelin prediction, inclusion of the free water compartment showed more distinction between gray and white matter compared to the model without free water (Fig. 3). Total water prediction was in line with the current gold standard for water imaging presented in the literature, including a hypointense globus pallidus, internal capsule, and white matter tracts with relatively increased signal in the thalamus and caudate (Fig. 4).Discussion

We demonstrated the capacity of BIOPHYSICSS-DL to estimate free water providing greater specificity to the tissue predictions and removing elements of the MRI signal related to water from the myelin and iron prediction. Addition of proton density information to the network allowed for estimation of the free water compartment with comparable contrast to the literature and without additional measurement time. Future studies will independently validate the quantitative accuracy of the map. Distributions of iron and myelin were slightly improved with the inclusion of free water, potentially due to the erroneous attribution of water-related alterations in relaxation rates to iron and myelin when free water was not properly modeled. Furthermore, we demonstrated for the first time that BIOPHYSICSS-DL can use higher order models to estimate tissue components from weighted images, which are more readily accessible in the clinical setting, promising to enable MRI-based bioquantification using clinical scans in the future.Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01NS114227, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001412, and by an equipment grant from Canon Medical Systems Corporation and Canon Medical Research USA, Inc. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Furthermore, the research was supported by the Free State of Thuringia within the ThiMEDOP project (2018 IZN 0004) with funds of the European Union (EFRE), the Free State of Thuringia within the thurAI project (2021 FGI 0008), the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD PPP 57599925), and an ISMRM Research Exchange Grant awarded to T.J.References

[1] Benslimane I., Grabner G., Hametner S., Jochmann T., Zivandinov R., Schweser F. Beyond qMRI: Biological tissue properties from single-subject unsupervised deep learning with theoretical signal constraints [abstract]. In ISMRM.; May 2022 London [2] S. Hametner, I. Wimmer, L. Haider, W. Brück, H. Lassmann, "Iron and oxidative damage in the multiple sclerosis brain", Journal of the Neurological Sciences, Volume 333, Supplement 1, Pages e386-e387, 2013. ISSN 0022-510X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.07.1403. [3] D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization, Dec. 2014 [4] Caan MWA, Bazin PL, Marques JP, de Hollander G, Dumoulin SO, van der Zwaag W. MP2RAGEME: T1 , T2* , and QSM mapping in one sequence at 7 tesla. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019 Apr 15;40(6):1786-1798. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24490. [5] Shah NJ, Abbas Z, Ridder D, Zimmermann M, Oros-Peusquens AM. A novel MRI-based quantitative water content atlas of the human brain. Neuroimage. 2022 May 15;252:119014. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119014. Epub 2022 Feb 22. PMID: 35202813.

Figures

Figure 2: A cadaver head (room-temperature) imaged at 7T using the MP2RAGE sequence4 for T1 mapping and a multi-echo gradient echo sequence for R2* mapping (yielding R2* and S0) and QSM (bottom row). T1-weighted Proton Density is equivalent to the S0 value determined in R2* fitting. Histological stains are shown at the top (TBB: top left; LFB-PAS: top right).

Figure 3: Inputs of the network (top row from left to right: R1, R2*, QSM, and T1w-PD) produce source estimations of iron, myelin, and water. The bottom row demonstrates estimations of myelin and iron using the same method without the total local water compartment.1 Inclusion of water compartments produced more distinct contrast between DGM regions and the surrounding white matter as seen in histology as well as removing the hypointense bias from the previous iron prediction.

Figure 4: Comparison of the estimated water map (left) to a literature free water atlas developed in Ref. [5] (stretched to match the current anatomy of the postmortem brain and converted to grayscale), the current state of the art. The contrast window of the water map was adjusted compared to Figure 3 to facilitate comparison with the literature atlas.