3548

Fiber-specific modelling in spherical deconvolution1Division Imaging and Oncology, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Gray Matter, Tractography & Fibre Modelling

Spherical deconvolution is commonly employed to reconstruct fiber orientations distributions with brain diffusion MRI. A key assumption in spherical deconvolution is that all brain fibers share the same microstructural properties. This is unlikely the case in white matter, but even more so in grey matter. Here, we propose a novel framework to perform spherical deconvolution with fiber specific models. As such, this framework allows to quantify diffusion properties associated to each fiber orientation. In this work, we showcase the application of this framework to investigate the organization of the brain cortex high resolution diffusion MRI data.Introduction

Diffusion MRI (dMRI) spherical deconvolution[1], [2] is a popular approach to infer the orientation of white matter (WM) brain fibers. A key assumption of most spherical deconvolution approaches is that all brain fibers share the same microstructural properties. As such, a single representative response function of brain fibers is derived from the data or pre-computed, and used throughout the brain for deconvolution to reconstruct fiber orientation distributions (FODs).Inappropriate deconvolution models (e.g., response functions) can lead to erroneous FODs[3]. Recently, we have shown that the estimation of FODs in cortical gray matter (GM) can be improved by separately modeling WM and GM during spherical deconvolution[4], using the diffusion kurtosis imaging[5] (DKI) representation and the NODDI[6]model, respectively. However, in such a framework only specific instances of the DKI and NODDI model were considered, which might not be sufficient to well capture FODs in highly heterogeneous structures such as the cortical GM.

In this work, we introduce a novel approach to spherical deconvolution able to account for varying properties in response function models corresponding to each FOD fiber separately. We showcase proof-of-concept of this framework by investigating its sensitivity to the layered organization of the GM in the motor cortex.

Methods

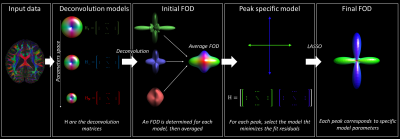

Our proposed approach is shown in Fig. 1. In short, we considered the DKI model with offset[7], which was introduced to account for signal restrictions and noise floor effects at high diffusion weightings. We generated 235 different deconvolution models based on multiple combinations of the axial and radial diffusivity of the diffusion tensor, mean kurtosis, and offset. These parameters were discretized as follows: axial diffusivity in 10 steps between 1.0 and 2.1x10-3 mm2/s; radial diffusivity in 3 steps between 0.1 and 0.5x10-3mm2/s; mean kurtosis in 3 step between 0 and 1; offset in 3 steps between 0 and 0.4.For each voxel, an initial FOD estimate is obtained by averaging the FODs obtained by performing deconvolution (using LASSO[8]) with each of the 235 models independently. For each fiber (i.e., FOD peak[9]), we determined which deconvolution model minimized the fit residuals. Finally, the FOD of each voxel was determined by performing LASSO regression using the fiber-specific deconvolution models.

We evaluated our approach on freely available high-resolution dMRI of the human brain[10]. The data were collected at 3T with imaging resolution 0.76mm isotropic, b = 0, 1000, 2500 s/mm2, 2709 gradient directions. The data were resampled to 0.3mm isotropic using b-spline interpolation to facilitate data interpretation. We focused our evaluation on one axial slice containing the primary motor and sensorimotor cortices, expecting to observe patterns in line with their known anatomical differences in their layered organization. We visually and quantitatively evaluated the spatial distribution of the fiber-specific models, and compared FODs to those obtained with our conventional multi-shell deconvolution framework.

Results

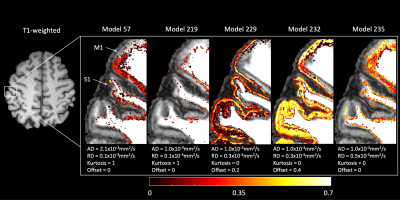

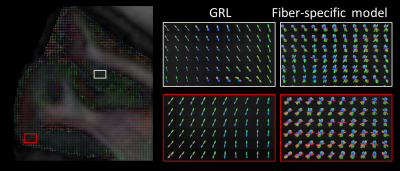

Figure 2 shows an example axial slice of the signal fractions corresponding to each deconvolution model relevant for at least one FOD peak in GM. Models corresponding to a diffusion tensor with low anisotropy but non-zero offset (~signal restriction), were the most used in the outer GM surface. Conversely, a combination of a model with high anisotropy and high kurtosis, and a model with low anisotropy and no kurtosis was mostly relevant in the inner GM surface, particularly in the primary motor cortex.Example FODs estimated with GRL and with the proposed method are shown in Figure 3. FODs reconstructed with peak-specific exhibit more crossing fibers in GM, as highlighted in the zoomed panels. Fiber configurations are spatially consistent, supporting the idea that such crossings are not the result of overfitting.

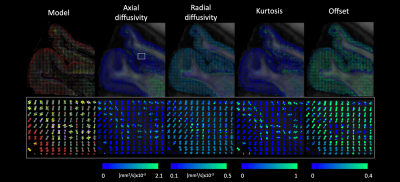

Figure 4 shows an axial rendering of the FODs color-encoded by the underlying peak-model properties. It can be observed that the FODs in the cortical ribbon exhibit a layered color-encoding. The zoomed panel shows a patch of peaks radial to the cortical surface with high kurtosis and axial diffusivity in the sensorimotor cortex.

Discussion and conclusion

In this work, we have introduced a novel approach to spherical deconvolution that considers peak-specific deconvolution models. When applied to high-resolution data of the brain, the proposed approach seems able to better capture the heterogeneity of the cortex than the conventional GRL approach. At the same time, it provided estimates of signal parameters associated with each peak which exhibited spatial consistency.This framework might prove beneficial in combination with frameworks aimed to perform fiber-specific analyses[11], to support the detection of alterations in neurological diseases[12]. As next steps, we aim to validate the framework with simulations, and to quantitatively evaluate the impact of fiber orientation modelling on FOD estimates.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] J. D. Tournier, F. Calamante, and A. Connelly, “Robust determination of the fibre orientation distribution in diffusion MRI: Non-negativity constrained super-resolved spherical deconvolution,” Neuroimage, vol. 35, pp. 1459–1472, 2007.

[2] F. Dell’Acqua, G. Rizzo, P. Scifo, R. A. Clarke, G. Scotti, and F. Fazio, “A model-based deconvolution approach to solve fiber crossing in diffusion-weighted MR imaging.,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 462–72, Mar. 2007.

[3] F. Guo, C. M. W. Tax, A. De Luca, M. A. Viergever, A. Heemskerk, and A. Leemans, “Fiber orientation distribution from diffusion MRI: Effects of inaccurate response function calibration,” J. Neuroimaging, no. May, pp. 1–17, 2021.

[4] A. De Luca, F. Guo, M. Froeling, and A. Leemans, “Spherical deconvolution with tissue-specific response functions and multi-shell diffusion MRI to estimate multiple fiber orientation distributions (mFODs),” Neuroimage, vol. 222, no. January, p. 117206, 2020.

[5] J. H. Jensen, J. a Helpern, A. Ramani, H. Lu, and K. Kaczynski, “Diffusional kurtosis imaging: the quantification of non-gaussian water diffusion by means of magnetic resonance imaging.,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 1432–40, Jun. 2005.

[6] H. G. Zhang, T. Schneider, C. a Wheeler-Kingshott, and D. C. Alexander, “NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain.,” Neuroimage, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 1000–16, Jul. 2012.

[7] J. Morez, J. Sijbers, F. Vanhevel, and B. Jeurissen, “Constrained spherical deconvolution of nonspherically sampled diffusion MRI data,” Hum. Brain Mapp., vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 521–538, 2021.

[8] E. J. Canales-Rodríguez et al., “Sparse wars: A survey and comparative study of spherical deconvolution algorithms for diffusion MRI,” Neuroimage, vol. 184, no. August 2018, pp. 140–160, 2019.

[9] B. Jeurissen, A. Leemans, J.-D. Tournier, D. K. Jones, and J. Sijbers, “Investigating the prevalence of complex fiber configurations in white matter tissue with diffusion magnetic resonance imaging.,” Hum. Brain Mapp., vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 2747–66, Nov. 2013.

[10] K. Setsompop et al., “High-Resolution In Vivo Diffusion Imaging of the Human Brain With Generalized Slice Dithered Enhanced Resolution : Simultaneous Multislice ( gSlider-SMS ),” vol. 151, no. March 2017, pp. 141–151, 2018.

[11] T. Dhollander et al., “Fixel-based Analysis of Diffusion MRI: Methods, Applications, Challenges and Opportunities,” Neuroimage, vol. 241, no. July, p. 118417, 2021.

[12] A. Dewenter et al., “Disentangling the effects of Alzheimer’s and small vessel disease on white matter fibre tracts,” Brain, pp. 1–35, Jul. 2022.

Figures